DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM is pleased to present YELLOW SKIRT, the first solo show in Europe by FATMA SHANAN (b. 1986 in Julis, IL / lives and works in Julis). In her new figurative-abstract oil paintings created for the exhibition, Shanan arranges complex relationships between bodies and spaces. Three large and several more intimately scaled paintings depict female figures, which Shanan describes as representations of herself, in diverse settings: reclining, floating above a carpet, stooped in front of a window, or in an open green field. The rugs in her compositions are not just networks of vibrant color and a reference to the Druze culture in which she was raised; they also function importantly as territories within the picture and mediators between bodies and architecture.

Raising questions concerning the meanings of specific places and how we relate to them and to ourselves, Shanan’s works shatter the bounds of identity and bodily presence in space. As the artist states directly in Doron J. Lurie’s The Carpet as Heterotopia: “In my paintings there is always a place, always an environment and always an examination of the relations between people and space. (…) Every place presents new challenges, yet the fundamental question is about the character of the space and the way it recharges my recurring themes. When a person changes place, whether by leaving their hometown or their homeland, the new environment places them face to face with their origins. In fact, they must examine how their place of origin is made present in space.“

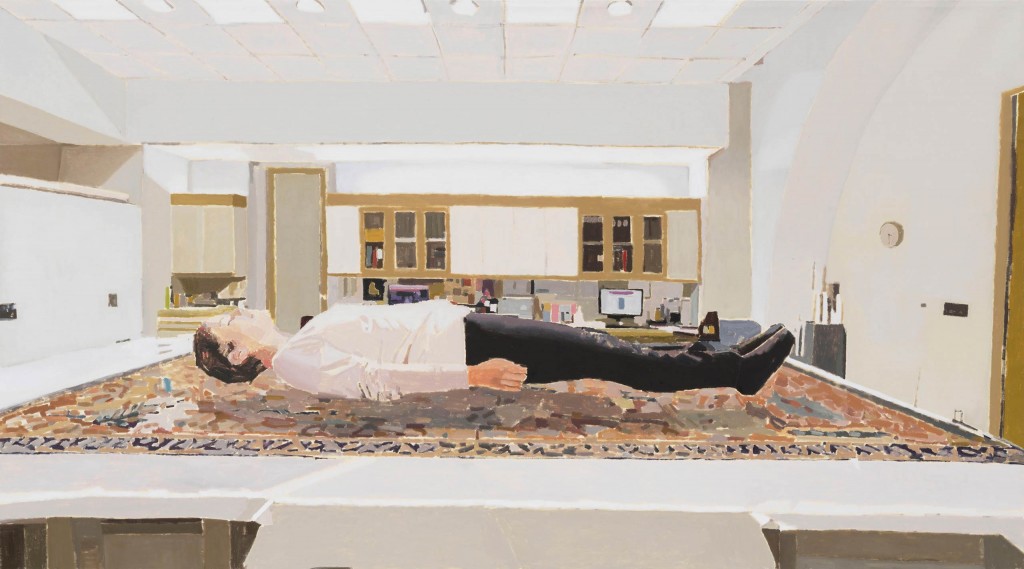

Shanan’s figures are shrouded in a state of alienation from their surroundings that is never unambiguously characterized. Have they fallen into a deep sleep or a kind of trance, is their self-absorption a form of inner resistance to the viewer’s importunate gaze or a peaceful and meditative coexistence with the pictorial space? The artist’s body as it appears in her pictures is rigid and passive, but it is never isolated from its context. Her work suspends the difference between figure and ground that defines classical portraiture, for the body cannot be thought without its environment.

In the works in the exhibition YELLOW SKIRT, it is time and again fabrics that effect this fusion of body and environment. The carpets, embodying the idea of color as place, seem to extend the figures into the space around them until all contours become indistinct. The titular garment in the painting “Yellow Skirt and Pink Flower” (2019) seems to awaken to a life of its own, its dynamic lines coalescing into an angular and voluminous sculpture that imbues the picture with the very motion that the recumbent body refuses to perform. The artist’s fascination for abstract color field painting is especially recognizable in the sketch-like “Floral Stocking” (2017).

In “Floating Self” (2019), Shanan’s painting transcends the laws of physics, giving the idea of coming adrift a Surrealist twist. Jettisoning the cliché of the flying carpet as a means of conveyance through space and time, it is the body of the reclining woman itself that levitates, hovering, straight as a pole and apparently impassive, in an interior from a dollhouse. The escape takes place in the mind alone, requiring no breakage or exertion of bodily force. And as though the unruly woman’s cunning victory over gravity were dismantling space itself, the floor appears to open up in the picture’s foreground.

The dominant element in the self-portrait “Green Window” (2018/19) is a large window looking out onto an exterior that exuberant vegetation has turned into a composition in various shades of green. One might almost overlook the stooped female figure concealing her face near the bottom edge of the picture. In “Field” (2019), the same tiny and oddly sculptural body—it is again the artist’s own—appears in the same pose in an open field. Yet by moving into a wider space, allowing the gaze to wander toward the distant horizon, Fatma Shanan’s art hardly cracks the shells of the painted bodies. Her compositions engage questions of being-in-the-world and the performative idea of carving out a physical and spiritual place.

The above is an excerpt from the essay contributed by Saskia Trebing for the exhibition catalogue, which will be available at the gallery in March 2019. For further information on the artist and the works or to request images, please contact Owen Clements, owen@dittrich-schlechtriem.com

Fatma Shanan studied with Eli Shamir and at the Oranim Academic College, Israel. Works by Shanan were included in the group exhibition ONLY THROUGH TIME TIME IS CONQUERED at the gallery in 2018. Shanan has won numerous fellowships and was awarded the Tel Aviv Museum of Art Haim Schiff Prize in 2016. An extensive solo exhibition of Shanan’s work on occasion of the award was presented at the museum in 2017. The catalogue accompanying that show is also available from the gallery.

DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM freuen sich, mit YELLOW SKIRT die erste europäische Einzelausstellung der israelischen Künstlerin FATMA SHANAN (geb. 1986 in Julis, IL / Lebt und arbeitet in Julis) zu zeigen. In ihren neuen, für die Ausstellung geschaffenen figurativ-abstrakten Ölgemälden arrangiert die Künstlerin komplexe Beziehungen zwischen Körpern und Räumen. In drei großformatigen und mehreren kleinformatigen Bildern sind Frauenfiguren, die Shanan als Repräsentationen ihrer selbst beschreibt, in verschiedenen Räumlichkeiten zu sehen: auf dem Rücken liegend, über einem Teppich schwebend, vorgebeugt vor einem großen Fensteroder mitten in einem offenen, grünen Feld. Die Teppiche sind in ihren Kompositionen nicht nur lebendige Farbzentren und eine Referenz an die Kultur der Drusen, in der sie aufgewachsen ist, sondern funktionieren vor allem als Territorien im Bild und Vermittler zwischen Körpern und Architektur.

Shanans Werke werfen Fragen zur Bedeutung bestimmter Orte und unserem Verhältnis zu ihnen und uns selbst auf und sprengen die Grenzen von Identität und körperlicher Gegenwart im Raum. Wie die Künstlerin in Doron J. Luries The Carpet as Heterotopia: In Conversation with Fatma Shanan beschreibt: „In meinen Bildern gibt es stets einen Ort, stets eine Umwelt und stets eine Untersuchung der Verhältnisse zwischen Mensch und Raum. (…) Jeder Ort bringt neue Herausforderungen mit sich, aber grundlegend geht es um den Charakter des Raums und die neue Energie, die er meinen wiederkehrenden Themen mitteilt. Wenn man den Ort wechselt, sei es durch einen Umzug, sei es, weil man seine Heimat verlässt, dann konfrontiert das neue Umfeld einen mit den eigenen Wurzeln – genauer mit der Frage, wie der Ort, in dem man verwurzelt ist, sich räumlich manifestiert.“

Shanans Figuren befinden sich in einem Zustand der Entfremdung von ihrer Umgebung, die nie eindeutig wird. Sind sie in tiefen Schlaf gefallen oder in eine Art Trance, ist es eine Form des inneren Widerstandes gegen den zudringlichen Blick des Betrachters oder eine friedliche, meditative Koexistenz mit dem Bildraum? Der Körper der Künstlerin ist in ihren Bildern erstarrt und passiv, aber nie kontextlos. Die klassische Portrait-Differenz zwischen Figur und Hintergrund wird ausgehebelt, weil der Körper nicht ohne seine Umgebung gedacht werden kann.

Bei den Werken der Ausstellung YELLOW SKIRT funktioniert diese Verschmelzung von Körper und Umwelt immer wieder über Textilien. Die Teppiche scheinen mit ihrer Idee von „color as place“die Figuren in den Raum auszudehnen, bis keine klaren Konturen mehr auszumachen sind. Der titelgebende gelbe Rock in „Yellow Skirt and Pink Flower“ (2019) entwickelt mit seinen dynamischen Linien ein Eigenleben, wird selbst zur kantig voluminösen Skulptur, die genau die Bewegung in das Gemälde bringt, die der liegende Körper verweigert. Im skizzenhaften „Floral Stocking“ (2017) zeigt sich die Faszination der Künstlerin für abstrakte Farbfeldmalerei besonders deutlich.

In „Floating Self“ (2019) überwindet Shanans Malerei die physikalischen Gesetze und lässt die Idee der Loslösung ins surrealistische kippen. Entgegen dem Klischee vom fliegenden Teppich als Transportvehikel durch Raum und Zeit hebt hier der Körper der Liegenden vom Boden ab und schwebt kerzengerade und scheinbar ungerührt in einem puppenstubenhaften Zimmer. Es ist ein Ausbruch, der rein geistig geschieht, ohne Trümmer oder körperliche Kraft. Als ob diese ungezogene Überlistung von Schwerkraft den Raum selbst zerlegt, scheint sich im Vordergrund des Gemäldes der Boden zu öffnen.

Auf ihrem Selbstportrait „Green Window“ (2018/19) dominiert ein großes Fenster, das den Blick auf ein pflanzenüberwuchertes Außen in verschiedenen Grüntönen erlaubt. Die vornübergebeugte Frauenfigur, die ihr Gesicht versteckt, verschwindet fast am unteren Bildrand. In „Field“ (2019) taucht dieser winzige, skulpturhafte Körper der Künstlerin in gleicher Haltung in einem freien Feld auf. Doch die Öffnung des Raumes mit Blick bis zum Horizont bedeutet in Fatma Shanans Kunst noch lange keine Öffnung der gemalten Körper. Die Kompositionen der Künstlerin handeln vom In-der-Welt-Sein und der performativen Idee, sich physisch und geistig einen Platz zu schaffen.

Der Ausschnitt stammt aus einem Aufsatz, den Saskia Trebing für den Ausstellungskatalog beigesteuert hat, der ab März 2019 über die Galerie zu beziehen ist. Für weitere Informationen zur Künstlerin und den Werken sowie Bildanfragen wenden Sie sich bitte an Owen Clements, owen@dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

Fatma Shanan studierte bei Eli Shamir und am Oranim Academic College in Israel. Arbeiten von Shanan waren 2018 in der Gruppenausstellung ONLY THROUGH TIME TIME IS CONQUERED zu sehen. Shanan hat zahlreiche Stipendien erhalten und wurde 2016 mit dem Haim-Schiff-Preis des Tel Aviv Museum of Art ausgezeichnet. Anlässlich des Preises präsentierte das Museum 2017 eine umfassende Einzelausstellung mit Shanans Werken. Der vom Museum herausgegebene Ausstellungskatalog ist ebenfalls über die Galerie zu beziehen.