The dilapidated former concrete plant in Stolpe in Brandenburg—the plans for its future envision a gradual transformation into a “culture park”—is a case in point, with construction materials and products handsomely crumbling under the elements: cast-concrete pipe elements, concrete slabs, heaps of gravel lie scattered across the premises right on the Hohensaaten Canal, which runs parallel to the Oder river. A website put up by the new owners solicits “makers & thinkers” who need a “workation in concrete” to become tenants, “take part in the development process,” and realize their “concrete utopia” (pun intended?) at the compound.

One of the first tenants is Simon Mullan, and one can hardly imagine a better fit for the aspiring “culture park.” After all, the Berlin-based artist’s work has long focused on the traces of Europe’s vanishing heavy industry and manufacturing sector and the concomitant demise of proletarian culture. The conversion of industrial brownfields at the hands of project developers occasionally provokes derision (due to the contrast between the dirty labor of yore and the future symbolic labor), anger (due to alleged gentrification effects), or idealization (of what once was). Mullan’s performative installations and sculptures, however, steer clear of parody, battle call, and sentimentalism alike. With great tenderness and respect, his work unearths the manifold expressions of a secondary sector that is shrinking and undergoing transformation by revaluing work attire and construction supplies as materials of art.

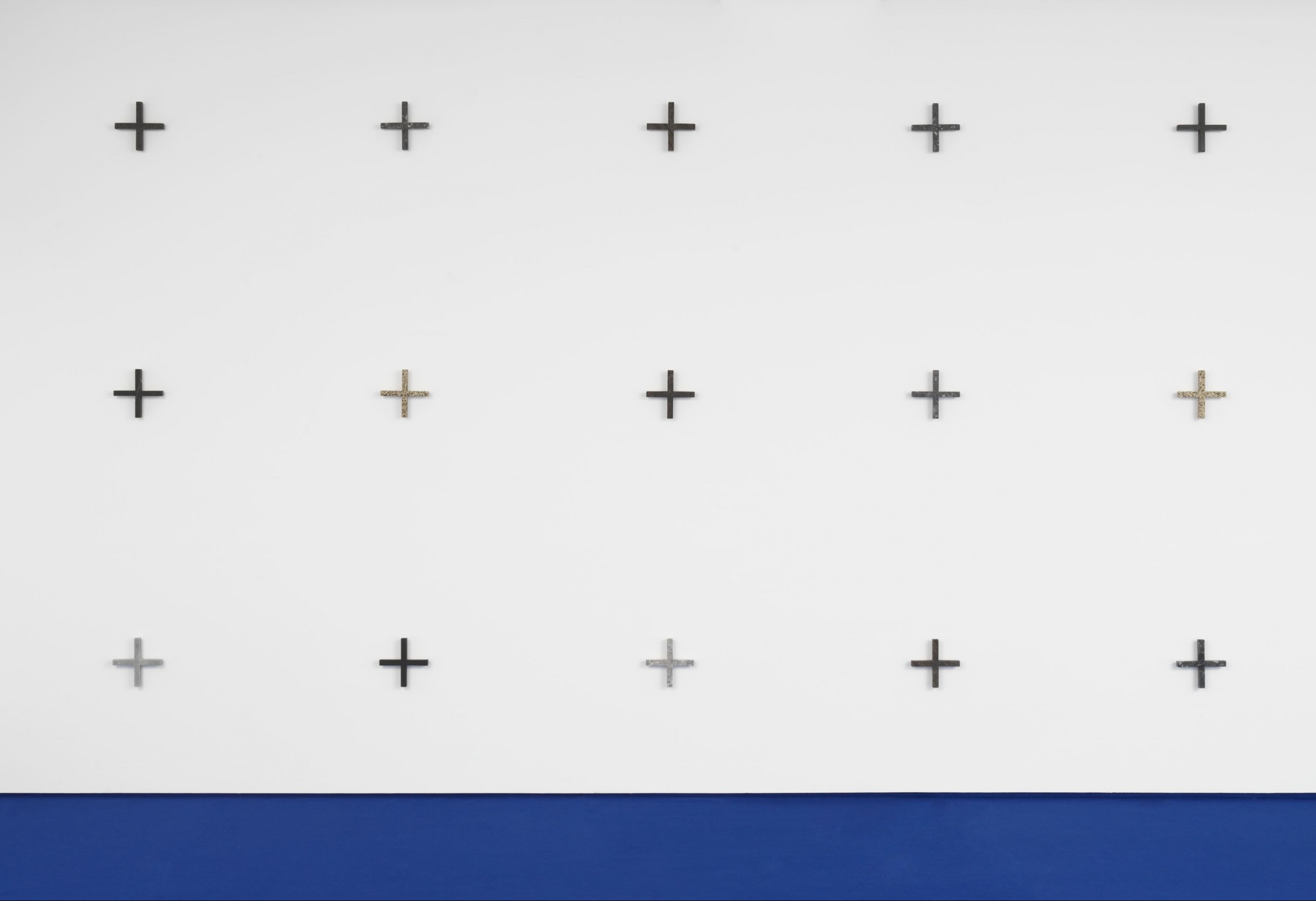

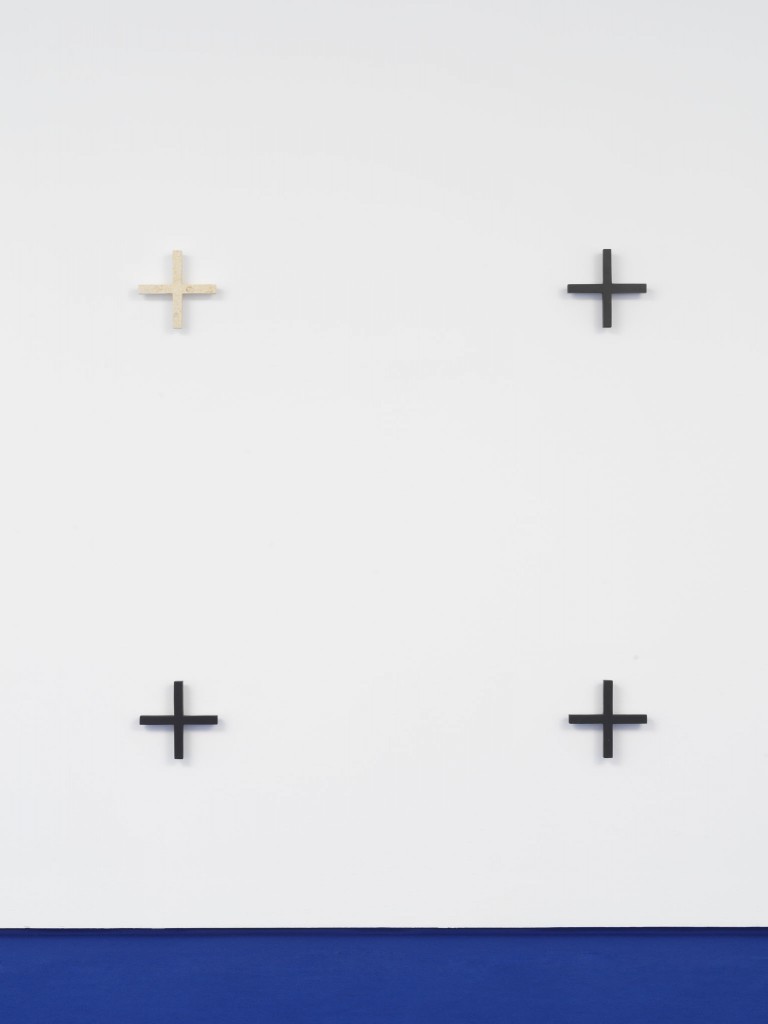

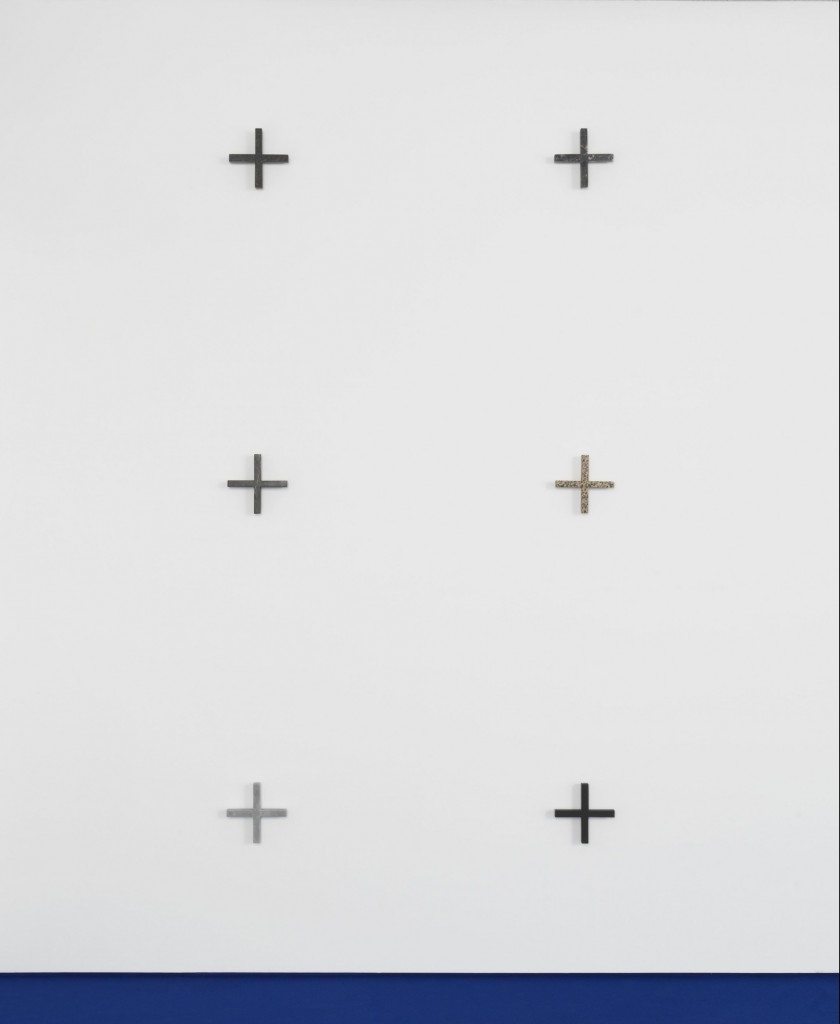

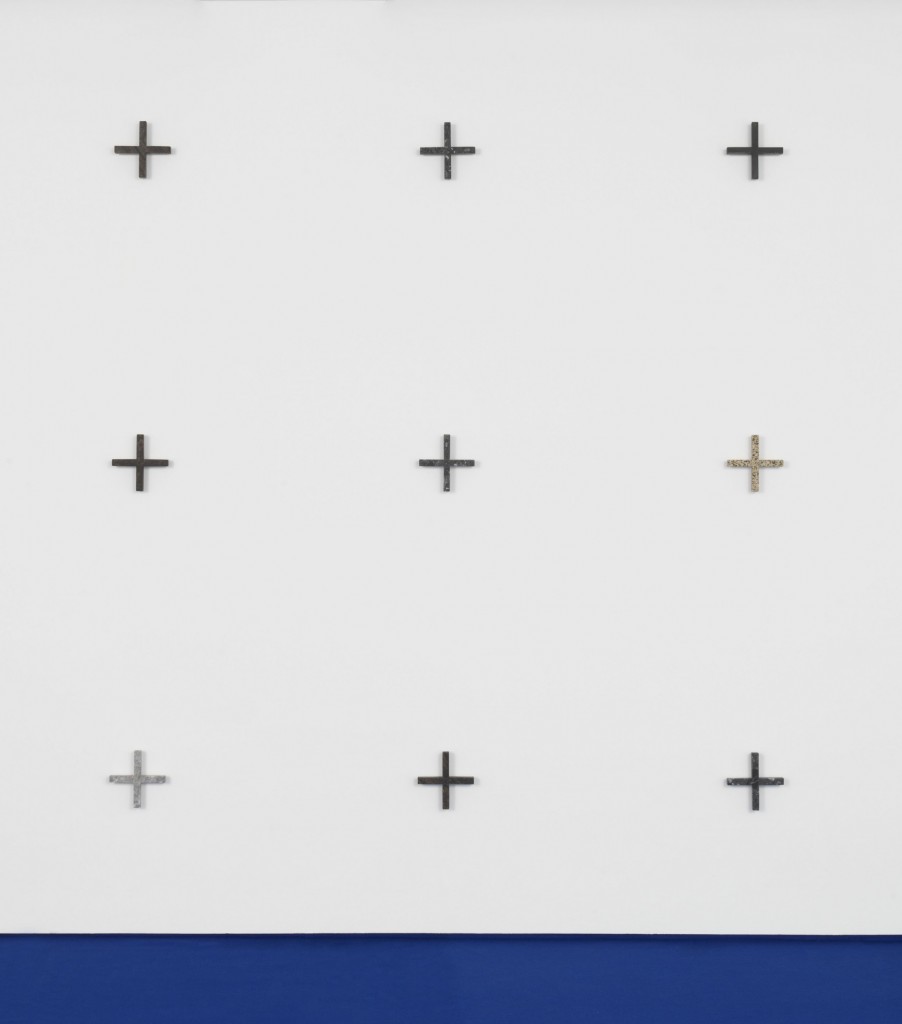

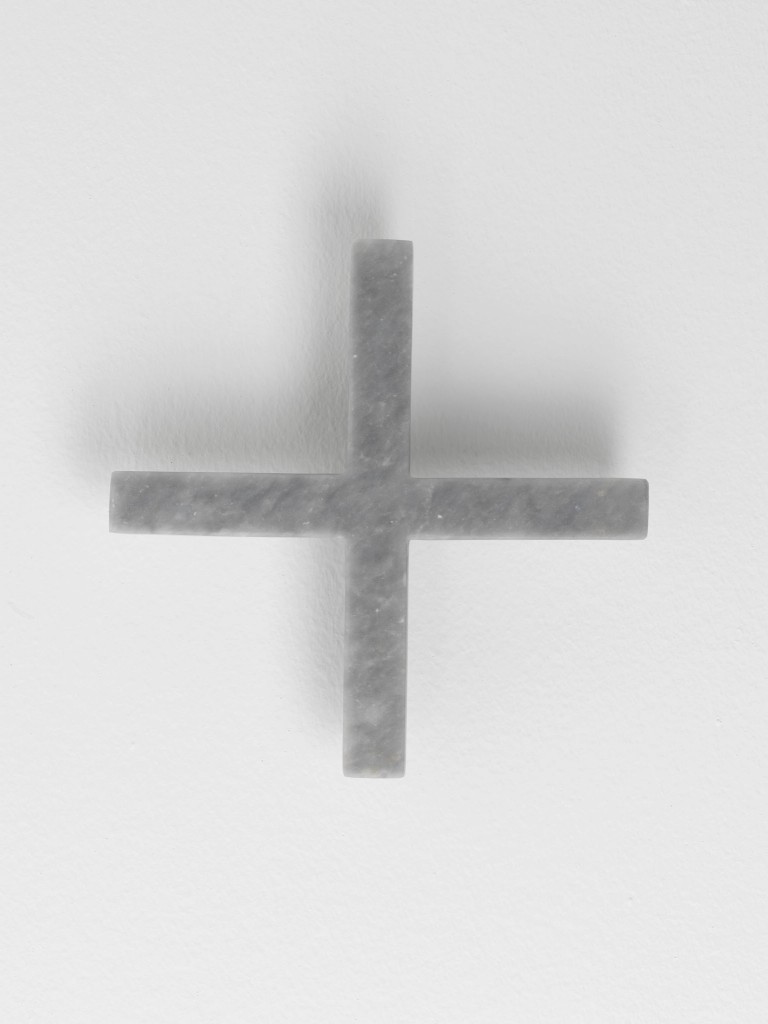

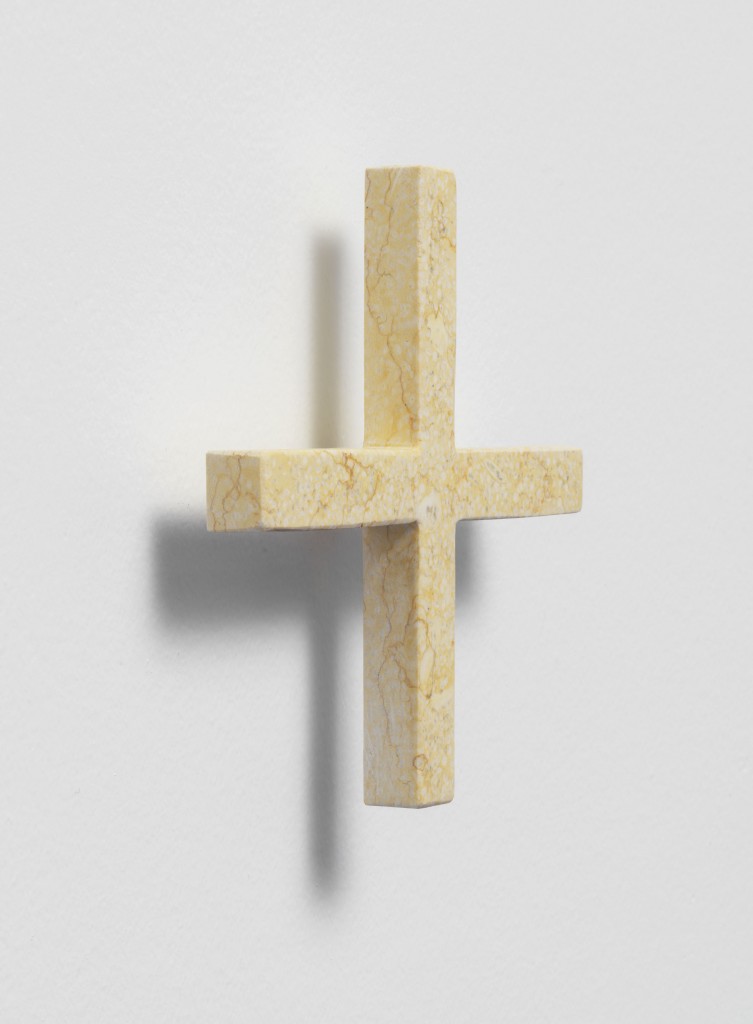

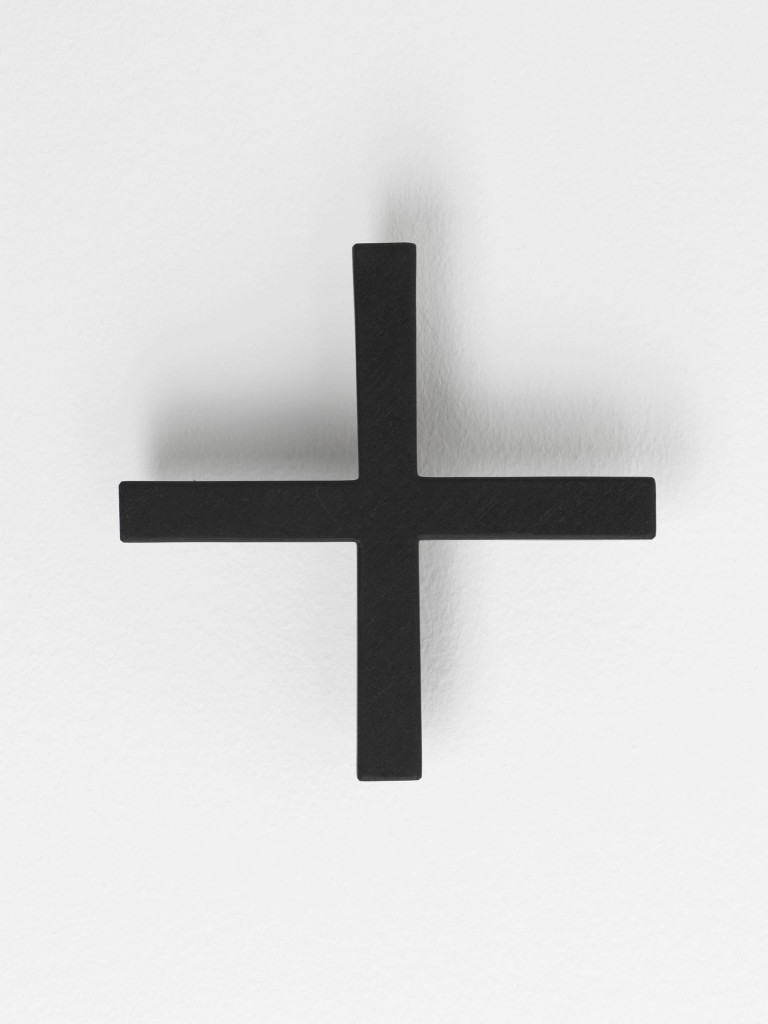

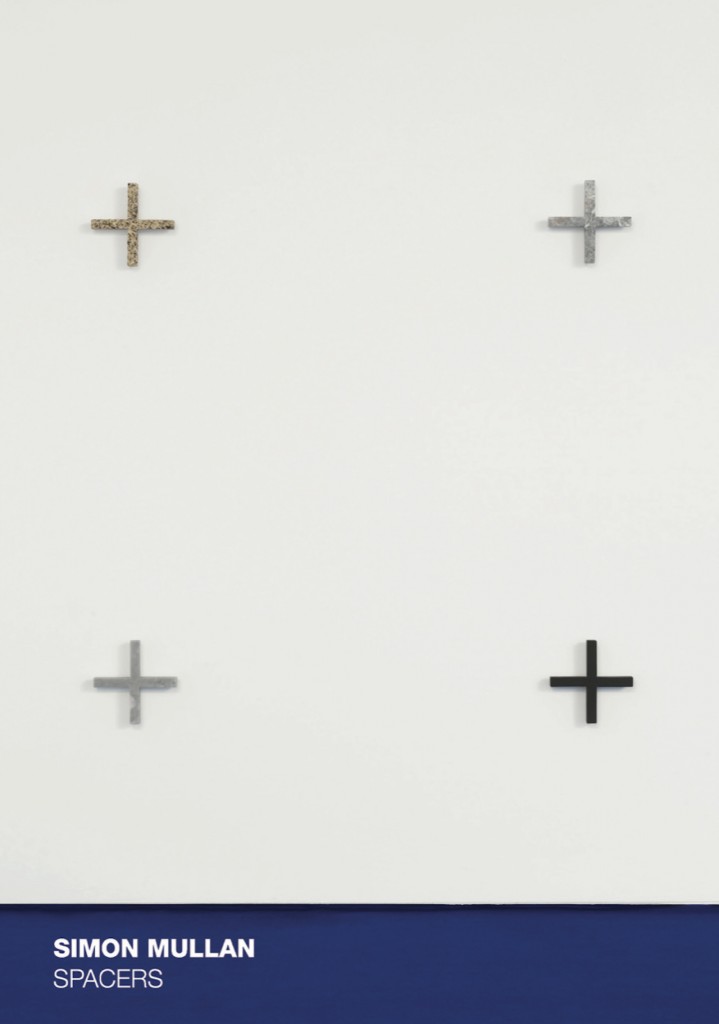

Vacancies and blanks are also the subject of Simon Mullan’s new exhibition “Spacers” at Galerie Dittrich & Schlechtriem—which, incidentally, is also his first show about Stolpe. The central installation consists of fifty-eight crosses: the objects, cut out of leftover stone slabs, are mounted on the large gallery showroom’s wall at equal intervals, defining square areas between them. These squares are one-to-ten replicas of the dimensions of a standard bathroom tile; the crosses, reproductions on the same scale of the spacers used to lay the tiles equidistant from each other.

Tiles have been a fixture of Simon Mullan’s art, cladding walls, sculptures, and medium-density fiberboards. This time, by contrast, it is the absence of the tiles that is on display, while only representations of the cross-shaped implement are to be seen: a tile setter would eventually remove the spacer crosses; here they are the elements that remain.

It is hard not to think of the Christian symbolism implied by the crosses, but even without this association, the uniformity and rhythm of the configuration establishes a quasi-sacred space. Its stillness contrasts with the noisy manufacture of the objects, for which the stonemason cuts the natural stone with a diamond blade.

The solemnity of the room is also blunted by the blue carpet that covers the entire floor of the gallery’s downstairs area. Simon Mullan based it on a found photograph that shows staff of Baustoffwerk Stolpe GmbH & Co. KG at a trade fair in the 1990s; the booth in which the building materials maker presented itself was laid with just such carpeting. The concrete plant had survived the reunification of Germany, not an easy feat at a time when the Treuhand, the agency tasked with privatizing the East German economy, liquidated many enterprises with long traditions. The employees in the photograph, which Mullan actually found in a building of the former plant, visibly try to fit into the new era—but in their awkwardness they look a little as though they were welcoming a high-ranking party functionary inspecting their Publicly Owned Enterprise.

The years after the fall of the Wall came with their own economic promises, though many of them would never be fulfilled. They were dressed up in soothing incantatory catchphrases and formulaic Anglicisms designed to dupe people into complacency: joint ventures were forged, a spectacular project in Brandenburg proposed to build “CargoLifters”—pipe dreams of widespread prosperity glammed up with a jargon no less dazzling than the lingo of today’s project developers and other “makers & thinkers.” The grandiosity of yesteryear’s fortune hunters echoes in the title Mullan chose for his exhibition: though “spacers” is simply the technical term for the cross-shaped pieces inserted between tiles, it conjures up a vision of intergalactic travel.

The building materials maker in Stolpe did ultimately meet its end, though not until a few years ago, when production was relocated to Poland. The company nameplate has been bleached by the sun. Simon Mullan recruited the help of local firefighters to take it down and set it up in the gallery’s entrance area for his exhibition. One of the company’s products is on view in the smaller showroom, a huge concrete drainage pipe element that stood on the premises and was repurposed as a planter. A similar element can be seen in the historic picture of the fair booth, with the mustachioed employees standing around it as though it were a bar table. A small tree has grown from the pipe that is now presented at the gallery; this, too, a visual trope for the new—in this instance, artistic—economy that is taking root on the former factory compound.

The ambivalent relationship between the art world and proletarian culture has always resonated in the forty-year-old Mullan’s work; so has the role that artists as service-sector workers play in the structural transformation of the economy more generally. Commentators who speak glibly of the transition from the industrial to the service society suggest a frictionless shift in which the old is simply supplanted by the modern. Real people lost and are still losing their jobs and their culture as the production facilities where they worked are shuttered, but when their lived lives come up at all in the debate, they are typically treated with folkloristic nostalgia; they are seen as a problem only when the pent-up frustration in the rust belts manifests itself in election results. In Stolpe and elsewhere, decisionmakers then often court artists, hoping that they will spruce up the buildings and infuse them with a new symbolism that will attract other, more amply capitalized service industries.

That is why artists’ attitude toward the working class as reflected in the history of art is inflected by a mix of mild embarrassment and soft-focus idealization: many artists articulated their yearning for a heroic production, for serial mass manufacturing and industrial scale, in their works—and yet always remained prototypes of the service society. In “Spacers,” this nexus is recognizable in each element: in the nameplate from Stolpe by the entrance to the enterprise that is Dittrich & Schlechtriem; in the souvenir from the historic fair booth at a gallery that fields its own booths at art fairs; in the crosses that are also frames and now frame the emptiness; in the borrowings from minimalism, which sought to efface any trace of the artist’s hand, of creative individuality.

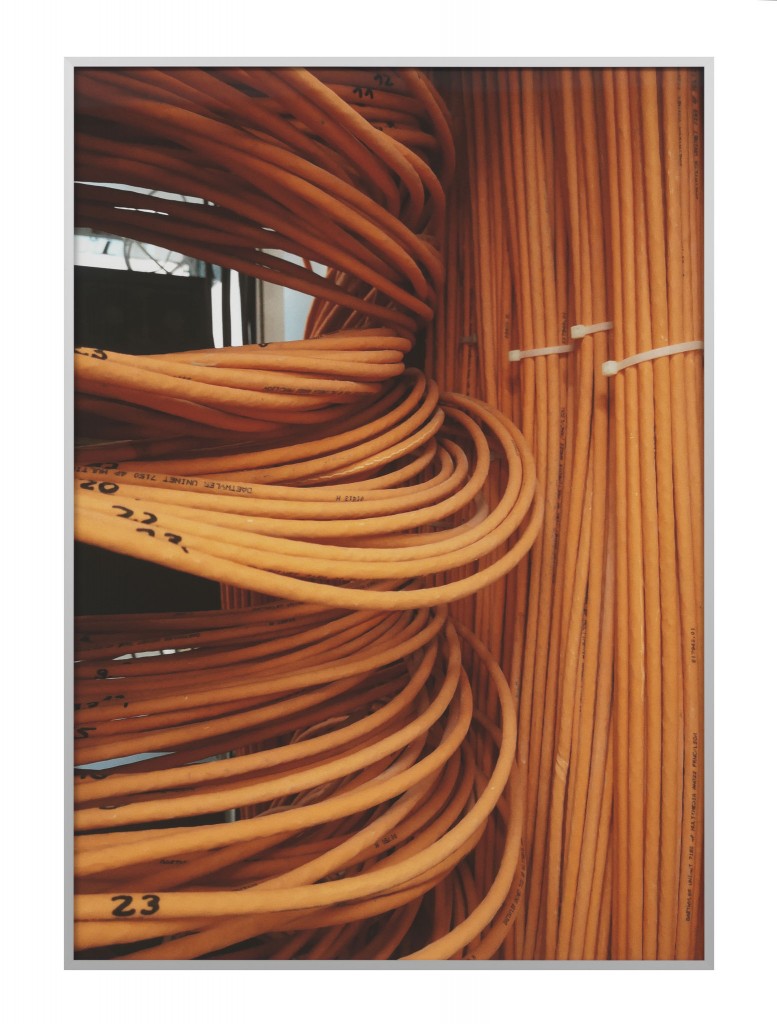

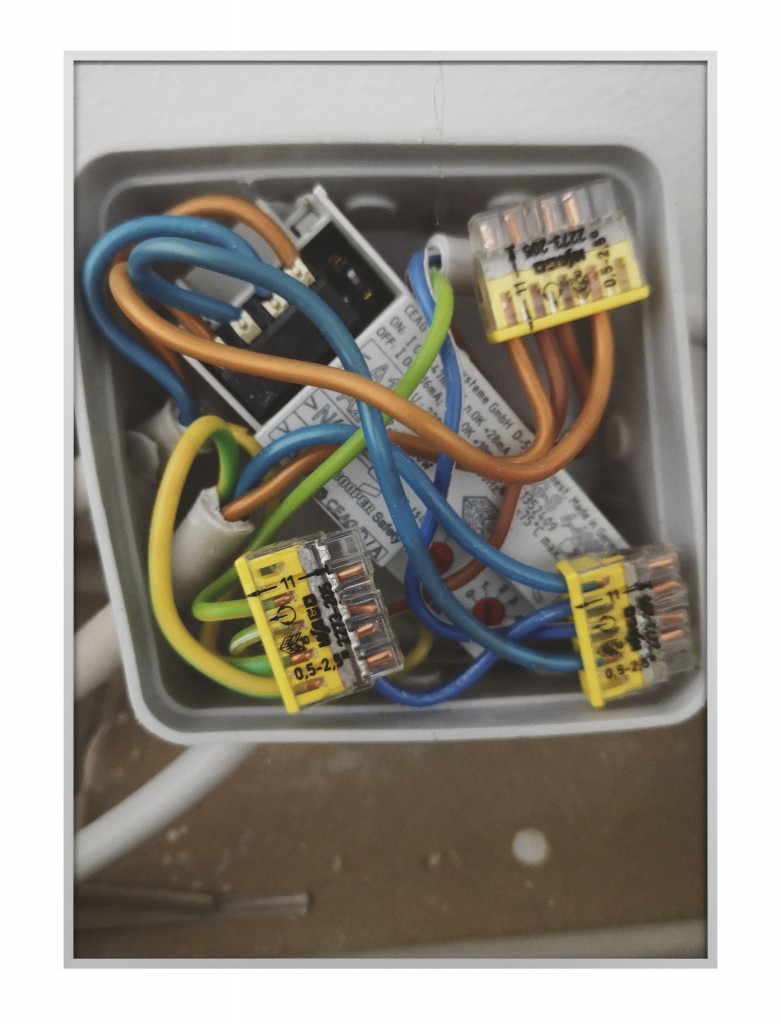

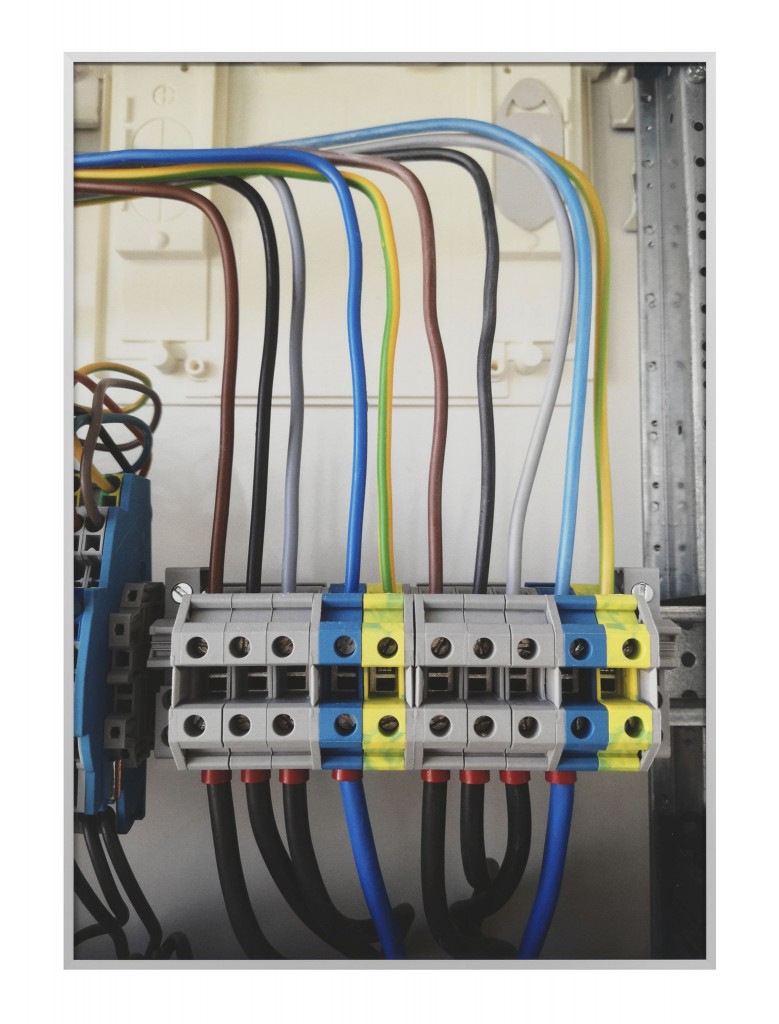

In Mullan’s life, too, art and manual labor go hand in hand. His father, a native of Northern Ireland, worked on construction sites in London and a shipyard in Kiel before becoming a teacher and told his son about his one-time colleagues’ wit. The young Mullan learned to lay tiles from a family friend who was an artist but earned a living as a handyman. Mullan himself combines the work on his art with gigs as an electrician. When he immerses himself in the culture of the working class, that is to say, he is not appropriating what is not his or putting it on a pedestal, but simply true to his own life story. He works without assistants and often collaborates with craftspeople. For the stone crosses, he asked the former stonecutter in Stolpe to help him and dusted off a machine that was installed at the concrete plant.

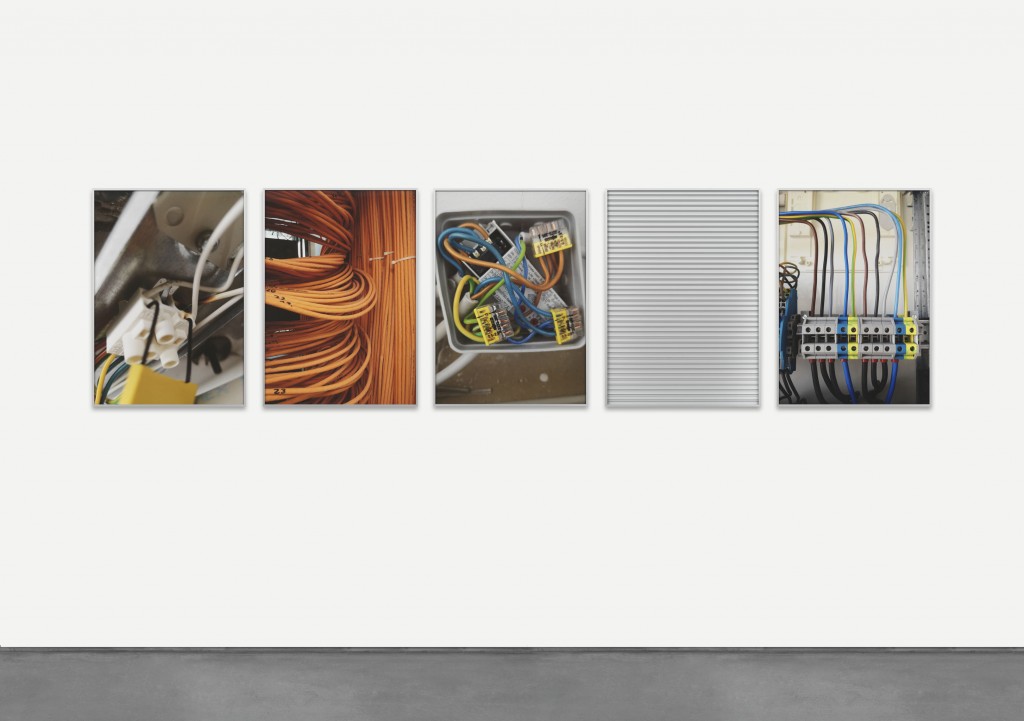

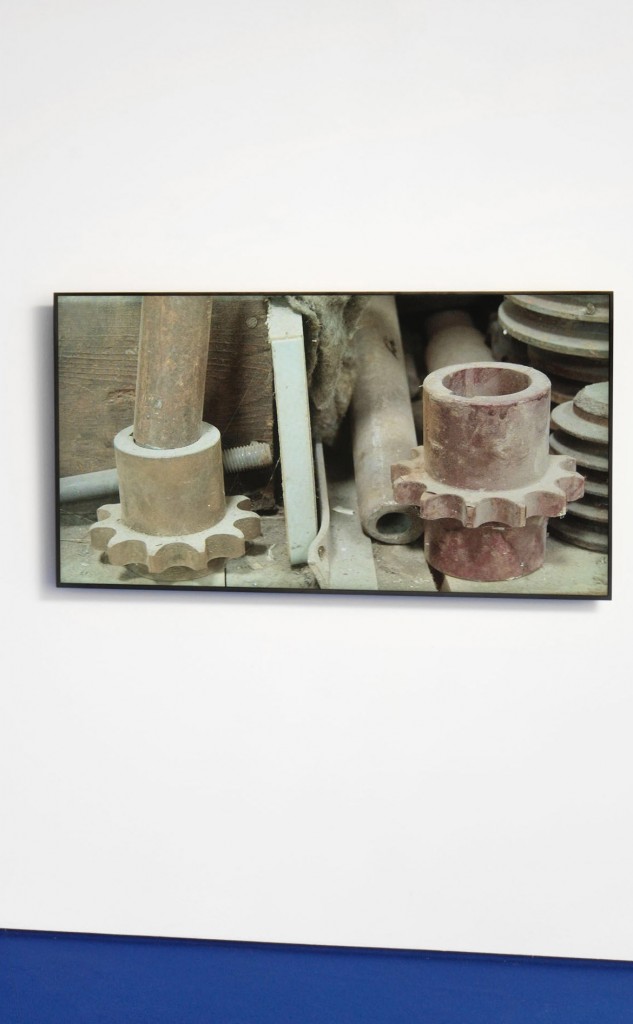

Considered in this light, the exhibition “Spacers” creates a space fraught with historical reminiscences that is about an erstwhile factory, about the artist’s studio, and about the ways in which the two scenes are interwoven. A film presents views of the dilapidated compound in Stolpe, abandoned machinery and tools, and, intercut between the images, selected words from a long conversation between the artist and a former employee:

BETON (CONCRETE)

WERK (WORK)

BETRIEB (PLANT)

CHEF (BOSS)

SCHACHT (WELL)

MESSE (FAIR)

They are echoes from another era, like repressed memories that surface only as decorative spoiled wares, if at all. Yet “Spacers” tells a much bigger story: of the enormous upheavals of globalization, their local impact—and art’s contribution to the valorization of the sites of the industries of the past.

Simon Mullan’s earlier works have given proof of the tile’s appeal, staging an unprepossessing construction staple like constructivist art. Eschewing tiles and grout lines and exhibiting the blanks instead, he now appears to be scaling back his ambitions as an artist in an effort to make room for memories. What the “concrete utopia” the owners wish to see realized on their former industrial site in Stolpe actually looks like: that is presumably a question to which they have no real answer, but this gesture of modesty by the artist Simon Mullan might be a model. There are ways to cushion the blow of wrenching economic change, yet the transformation itself is most likely unstoppable. What remains possible is a respectful engagement with history and an awareness of the situation of people whom the contemporary world has left out in the cold.

DANIEL VÖLZKE was born in East Germany in 1975. He lives and works in Berlin as an editor of “Monopol,” where he oversees the art magazine’s online presence.

Auch auf der Brache der ehemaligen Betonfabrik im brandenburgischen Stolpe, die sich so langsam in einen „Kulturpark“ verwandeln soll, verwittern Baustoffe und Produkte auf ansehnliche Weise: Auf dem Gelände direkt am Hohensaatener Kanal, der parallel zur Oder verläuft, liegen aus Beton gegossene Rohrteile, Betonplatten, Kieshaufen. Eine Website der neuen Eigentümer wirbt um „Makers & Thinkers“, die eine „Workation in Beton“ brauchen, sich als Mieter:innen „an dem Entwicklungsprozess beteiligen“ und hier eine „konkrete Utopie“ (ein Wortspiel?) verwirklichen wollen.

Einer der ersten Mieter ist Simon Mullan, und der angehende „Kulturpark“ hätte kaum einen besseren finden können. Der Berliner Künstler beschäftigt sich schließlich in seiner Kunst schon seit langem mit den Spuren der in Europa verschwindenden Schwer- und verarbeitenden Industrie und der damit untergehenden proletarischen Kultur. Auch wenn die Umwandlung industrieller Brachen durch Projektentwickler:innen gelegentlich Häme (wegen des Kontrastes zwischen der einstigen schmutzigen Arbeit und der zukünftigen symbolischen Arbeit), Wut (wegen vermeintlicher Verdrängung) oder Verklärung (dessen, was einmal war) provoziert, haben Mullans performative Installationen und Skulpturen nichts von Parodie, Kampfansage oder Sentimentalität. Stattdessen spürt er mit großer Zärtlichkeit und Respekt den vielfältigen Ausdrucksformen eines schrumpfenden und sich wandelnden sekundären Sektors nach, indem er Arbeitskleidung und Baustoffe zu künstlerischem Material umwertet.

Um Leerstellen geht es auch in Simon Mullans neuer Ausstellung „Spacers“ in der Galerie Dittrich & Schlechtriem – und nebenbei zum ersten Mal um Stolpe. Die zentrale Installation besteht aus 58 Kreuzen: Die aus Restposten von Steinplatten geschnittenen Objekte hängen in einem gleichmäßigen Abstand voneinander an der Wand des großen Galerieraumes und definieren so quadratische Flächen zwischen ihnen. Diese Quadrate entsprechen im Maßstab eins zu zehn der Größe einer Standard-Badezimmer-Fliese, die Kreuze im gleichen Maßstab der Größe von Fliesenkreuzen, mit deren Hilfe die Kacheln in gleichmäßigem Abstand voneinander verlegt werden.

Simon Mullan hat immer wieder Fliesen benutzt in seiner Kunst, Wände, Skulpturen und MDF-Platten damit verkleidet. Diesmal aber wird die Abwesenheit der Fliesen ausgestellt und nur Darstellungen des kreuzförmigen Hilfsmittels sind zu sehen: Während beim Kacheln die Abstandhalter-Kreuze am Ende entfernt werden, sind sie hier die verbleibenden Elemente.

Die christliche Symbolik der Kreuze drängt sich auf, aber auch ohne sie entsteht durch die Gleichmäßigkeit und den Rhythmus der Gestaltung ein quasi-sakraler Raum, dessen Stille im Kontrast zur geräuschvollen Herstellung der Objekte steht, wenn der Steinmetz mit dem Diamantschneider durch den Naturstein fräst.

Das Weihevolle des Raumes wird auch gebrochen durch einen blauen Teppich, der den Boden des gesamten Untergeschosses der Galerie bedeckt. Simon Mullan hat eine Vorlage dafür in einem Foto gefunden, das Mitarbeiter der Baustoffwerk Stolpe GmbH & Co. KG in den 90er-Jahren auf einer Messe zeigt, der Stand ausgelegt mit eben einem solchen Teppich. Die Betonfabrik hatte sich in das wiedervereinigte Deutschland hinübergerettet, keine Selbstverständlichkeit in einer Zeit, in der die Treuhandanstalt viele traditionsreiche ehemalige DDR-Betriebe abwickelte. Die Mitarbeiter auf dem Foto, das Mullan tatsächlich in einer Halle der einstigen Fabrik gefunden hat, geben sich sichtbar Mühe, in die neue Realität zu passen – wirken aber in ihrer Verlegenheit ein bisschen so, als würde gerade ein hoher Parteifunktionär den Volkseigenen Betrieb besichtigen.

Die Nachwende-Ära hatte ihre eigenen ökonomischen Versprechen, die häufig uneingelöst blieben, aber damals umrankt wurden von einlullenden Beschwörungsformeln und englischsprachigen Übertölpelungsfloskeln wie der vom Joint Venture oder der vom spektakulären Brandenburger „CargoLifter“– blühende Landschaften verheißende Visionen, die mit einem Jargon gefüttert wurden, der dem heutiger Projektentwickler:innen und „Makers & Thinkers“ in nichts nachsteht. In Mullans Ausstellungstitel hallt die Großspurigkeit der Glücksritter von damals nach: „Spacers“ bezeichnet zwar einfach die kreuzförmigen Abstandhalter, aber klingt doch nach Aufbruch in den Weltraum.

Für das Baustoffwerk in Stolpe kam das Aus dann am Ende doch noch, allerdings erst vor einigen Jahren: Die Produktion wanderte nach Polen ab. Das Firmenschild ist inzwischen von der Sonne ausgebleicht. Simon Mullan hat es mit örtlichen Feuerwehrleuten abmontiert und für seine Ausstellung in den Eingangsbereich der Galerie gestellt. Im kleineren Ausstellungsraum ist ein Produkt der Firma zu sehen, ein riesiges Abflussrohrteil aus Beton, das auf der Brache stand und zum Pflanzenkübel umfunktioniert wurde. Ein ähnliches Teil ist auch auf dem historischen Bild vom Messestand zu sehen, die schnauzbärtigen Mitarbeiter stehen an ihm wie an einem Stehtisch. Aus dem Abflussrohrteil, das nun in der Galerie präsentiert wird, ist ein kleiner Baum gewachsen; auch das ein Bild für die neue Bewirtschaftung des Geländes, diesmal durch Künstler:innen.

Im Werk des 40-jährigen Mullan schwingt das ambivalente Verhältnis zwischen Kunstwelt und proletarischer Kultur immer mit, auch der Anteil von Künstler:innen als Dienstleister:innen am Strukturwandel überhaupt. Wer leichtfertig vom Übergang der Industrie- in die Dienstleistungsgesellschaft spricht, suggeriert einen reibungslosen Ablauf, in dem etwas Altes einfach durch etwas Modernes ersetzt wird. Das gelebte Leben der Menschen, die ihre Arbeit und ihre Kultur mit der Abwicklung ihrer Produktionsstätten verloren haben und weiter verlieren, wird indes oft folkloristisch verklärt oder erst dann als Problem gesehen, wenn der Frust aus den rust belts sich in Wahlergebnissen niederschlägt. Wie in Stolpe sind es dann oft die Künstler:innen, um die geworben wird. Sie sollen alles baulich und symbolisch schön herrichten und so weitere, solventere Dienstleister:innen anzuziehen.

In der Kunstgeschichte zeigt sich deshalb ein leicht verschämtes, leicht idealisierendes Verhältnis von Künstler:innen zur Arbeiterklasse: Viele haben ihre Sehnsucht nach einer heroischen Produktion, serieller Massenfertigung und industrieller Größe in ihren Werken ausgedrückt – und sind doch immer Prototypen der Dienstleistungsgesellschaft geblieben. In „Spacers“ ist dieses enge Verhältnis in allen Elementen ablesbar: im Gewerbeschild aus Stolpe am Eingang der Firma Dittrich & Schlechtriem; in der Erinnerung an den historischen Messestand in einer Galerie, die auch an Kunstmessen teilnimmt; an den Kreuzen, die gleichzeitig Rahmen sind und jetzt das Nichts rahmen; an den Anleihen aus der Minimal Art, die jede individuelle Künstler:innen-Handschrift löschen wollte.

Auch in Mullans Leben gehen Kunst und handwerkliche Arbeit eng zusammen. Sein nordirischer Vater hat, bevor er Lehrer wurde, auf Baustellen in London und einer Kieler Werft gearbeitet und seinem Sohn von dem Witz der einstigen Kollegen erzählt. Das Fliesenlegen lernte Mullan als junger Mensch von einem Freund der Familie, der Künstler war, aber als Handwerker sein Geld verdiente. Mullan selbst arbeitet heute nicht nur als Künstler, sondern auch als Elektriker. Wenn er sich also mit der Kultur der Arbeiterklasse beschäftigt, ist das keine Aneignung und Heroisierung , sondern erklärt sich aus der eigenen Biografie. Er arbeitet ohne Assistenz und häufig in Kooperation mit Handwerkern. Auch die Steinkreuze sind gemeinsam mit dem ehemaligen Steinmetz von Stolpe zurechtgeschnitten, auf einer Maschine, die Teil der Betonfabrik war.

Die Ausstellung „Spacers“ schafft so einen mit Geschichte aufgeladenen Raum, in dem es um eine ehemalige Fabrik geht, um das Atelier des Künstlers und die Verschränkung dieser beiden Orte. Ein Film zeigt Bilder von der Stolper Brache, zurückgelassene Maschinen sowie Werkzeug, dann zwischen den Bildern einzelne Wörter aus einem langen Gespräch, das der Künstler mit einem ehemaligen Mitarbeiter der Fabrik geführt hat:

BETON

WERK

BETRIEB

CHEF

SCHACHT

MESSE

Es sind Echos aus einer anderen Zeit, wie etwas Verdrängtes, das höchstens noch als dekorative Bruchware vorkommt. „Spacers“ allerdings erzählt von etwas viel Größerem, nämlich den gigantischen Umwälzungen der Globalisierung, ihren lokalen Auswirkungen – und den Anteil der Kunst an der Aufwertung ehemals industrieller Orte.

Simon Mullan hat in seinem bisherigen Werk die Attraktivität der Fliese unter Beweis gestellt, indem er diesen banalen Baustoff wie konstruktivistische Kunst inszenierte. Wenn er nun auf Fliesen und Fugen verzichtet und stattdessen die Leerräume ausstellt, wirkt das wie eine Zurücknahme seiner künstlerischen Ambition, um Raum für Erinnerung zu schaffen. Welche „konkrete Utopie“ sich die Eigentümer der Stolper Brache wünschen, können sie sich wahrscheinlich selbst kaum beantworten, aber diese Geste der Bescheidenheit durch den Künstler Simon Mullan wäre vielleicht ein Modell dafür. Der Strukturwandel lässt sich zwar politisch abfedern, aber wohl kaum aufhalten. Was aber möglich bleibt, ist ein respektvoller Umgang mit der Geschichte und ein Bewusstsein für die Menschen, mit denen es die Verhältnisse nicht gut meinen.

DANIEL VÖLZKE wurde 1975 in der DDR geboren. Er arbeitet in Berlin als Redakteur des Kunstmagazins „Monopol“, wo er den Onlineauftritt leitet.