DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM proudly present PROPEL, Daniel Hölzl’s second solo exhibition at the gallery, opening during Berlin Art Week on Thursday, September 11, 2025, 6–10 PM as part of Gallery Night and on view through October 25, 2025. The exhibition builds on the artist’s ongoing material and conceptual research into cycles of transformation, industrial memory, and the poetics of propulsion—extending the themes introduced in his 2022 solo exhibition GROUNDED.

Hölzl’s multidisciplinary practice is defined by a sensitive yet critical engagement with the systems and materials that shape modern life. Fusing sculptural engineering with ephemerality, he explores the entangled lifecycles of aviation, energy, and ecological consciousness.

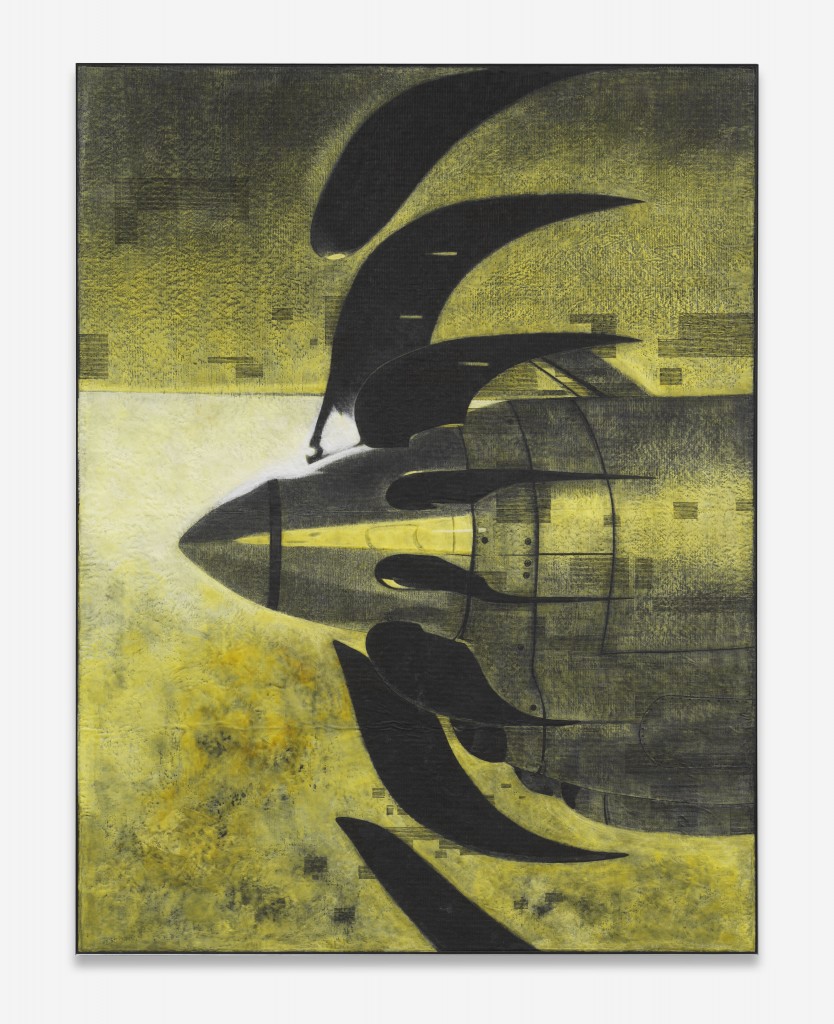

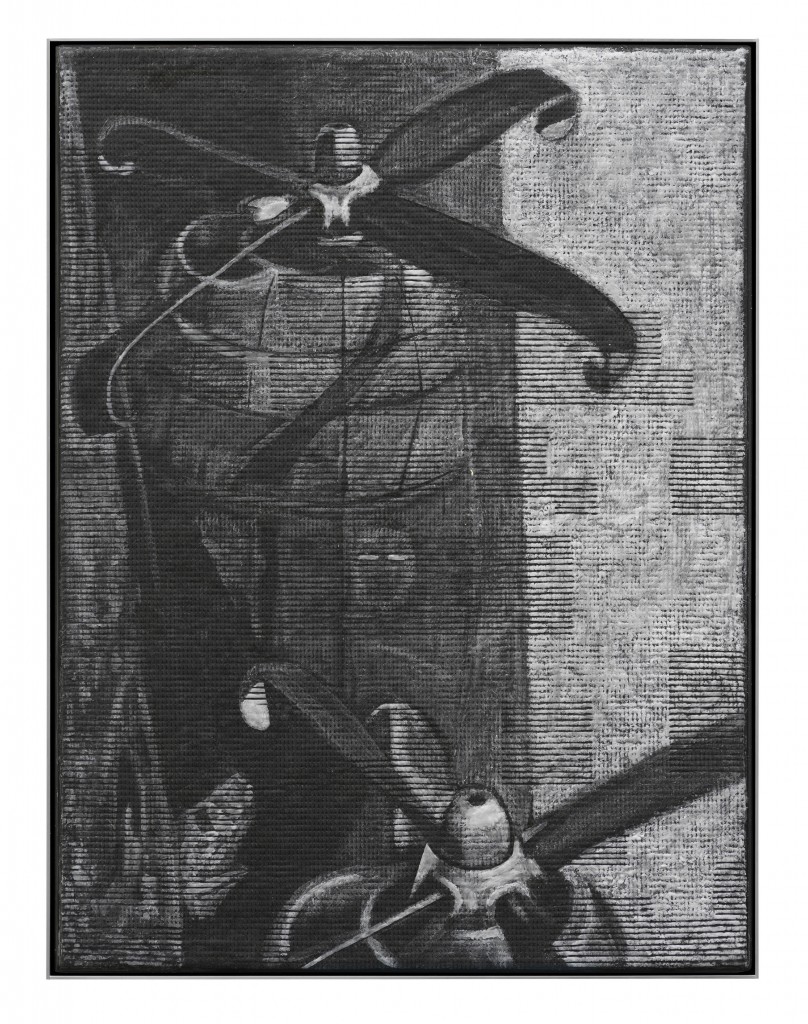

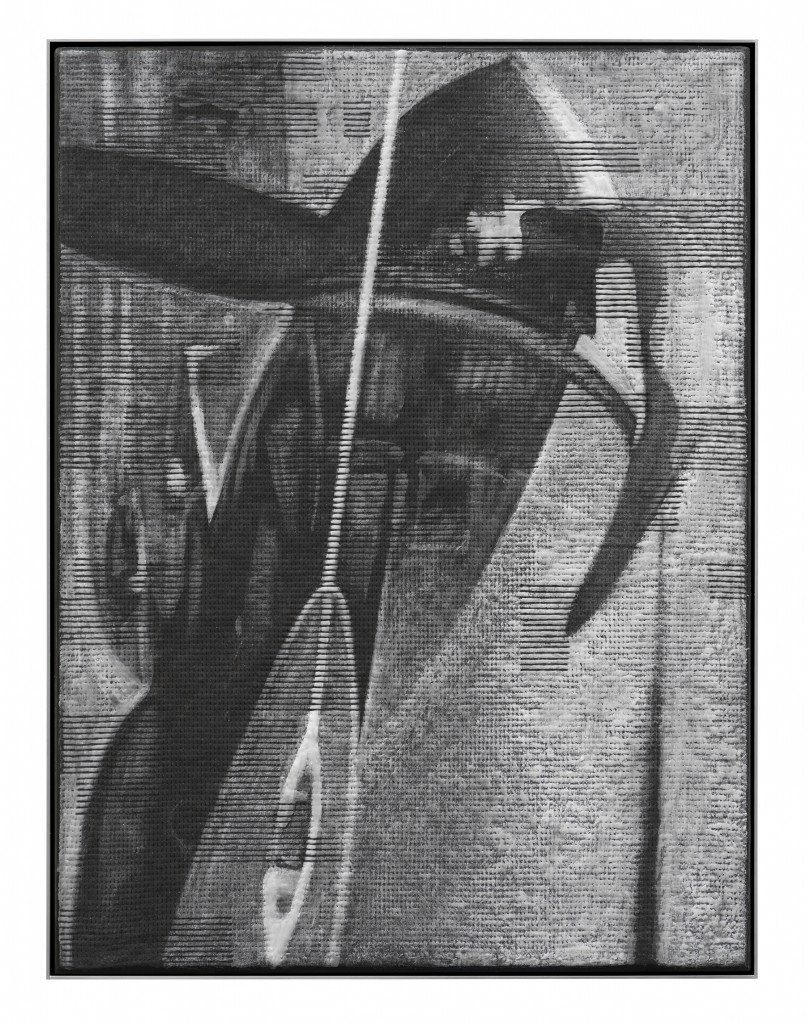

At the core of PROPEL are three types of propellers—each a meditation on movement, innovation, collapse, and transformation—recalling the forms of both seed and bomb, origin and end.

The first, attached to a historic radial engine from a “candy bomber,” features deformed aluminum blades that graze the floor, suspended between flight and failure. Meanwhile, at the center of the gallery, three hollow carbon-fiber propellers spin overhead in a kinetic installation, releasing drops of pigment—black ink made from recycled air pollution—that arc through space, striking the walls and gradually forming a continuous line. The third group, cast in paraffin wax, was warped by sunlight and continues to shift with the ambient temperature, echoing the entropy of both technology and nature.

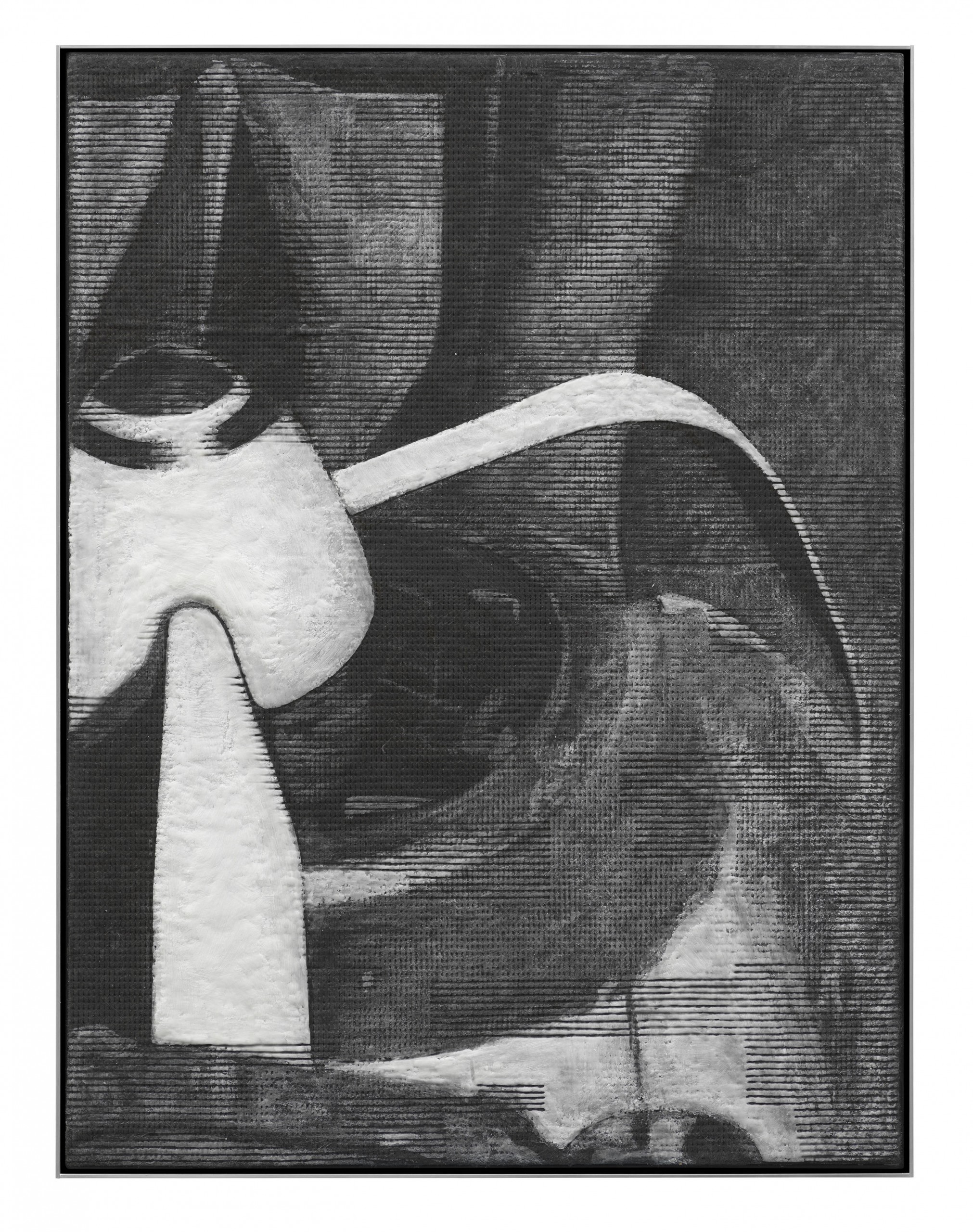

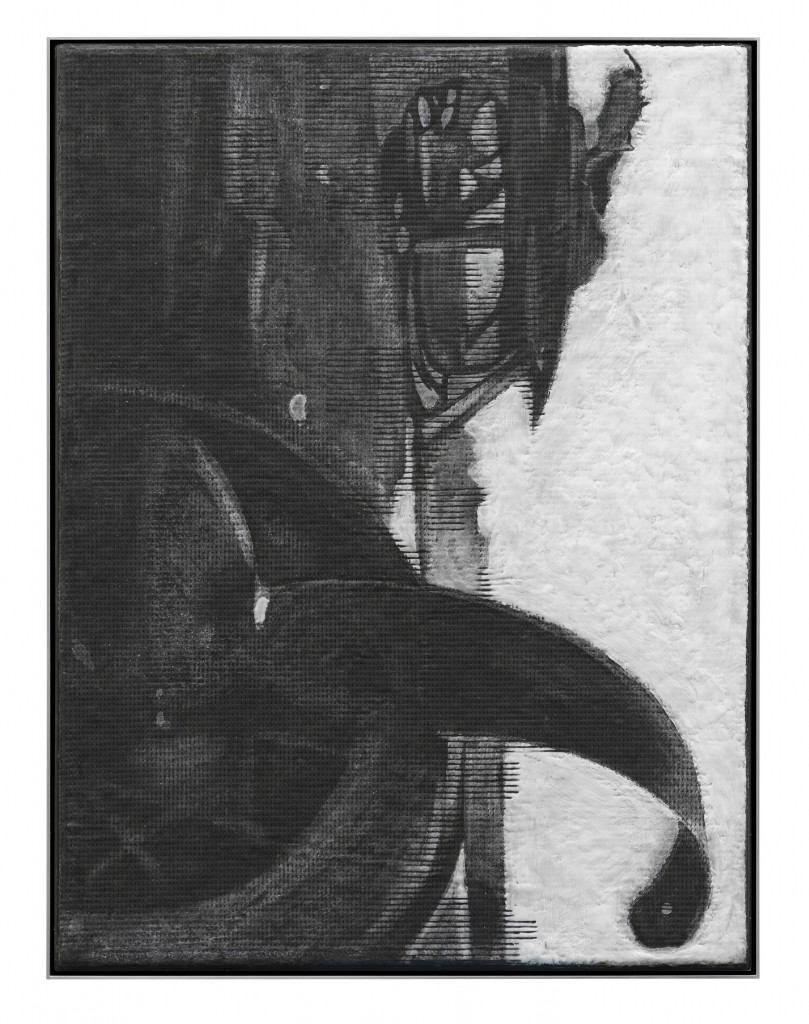

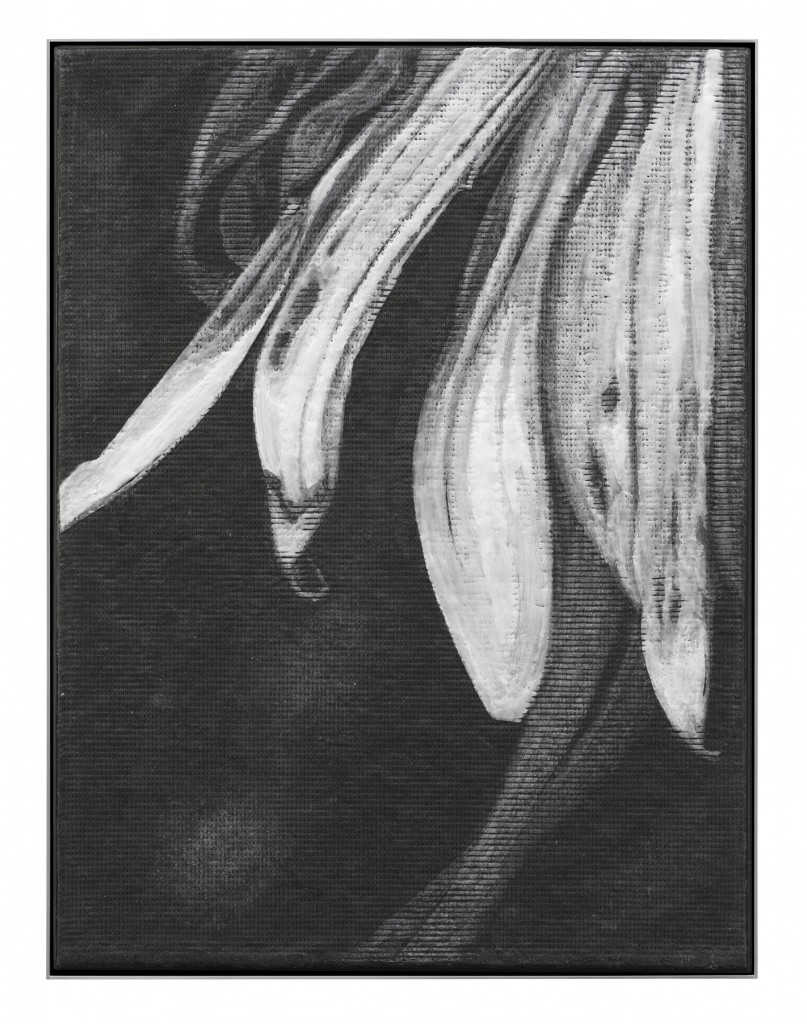

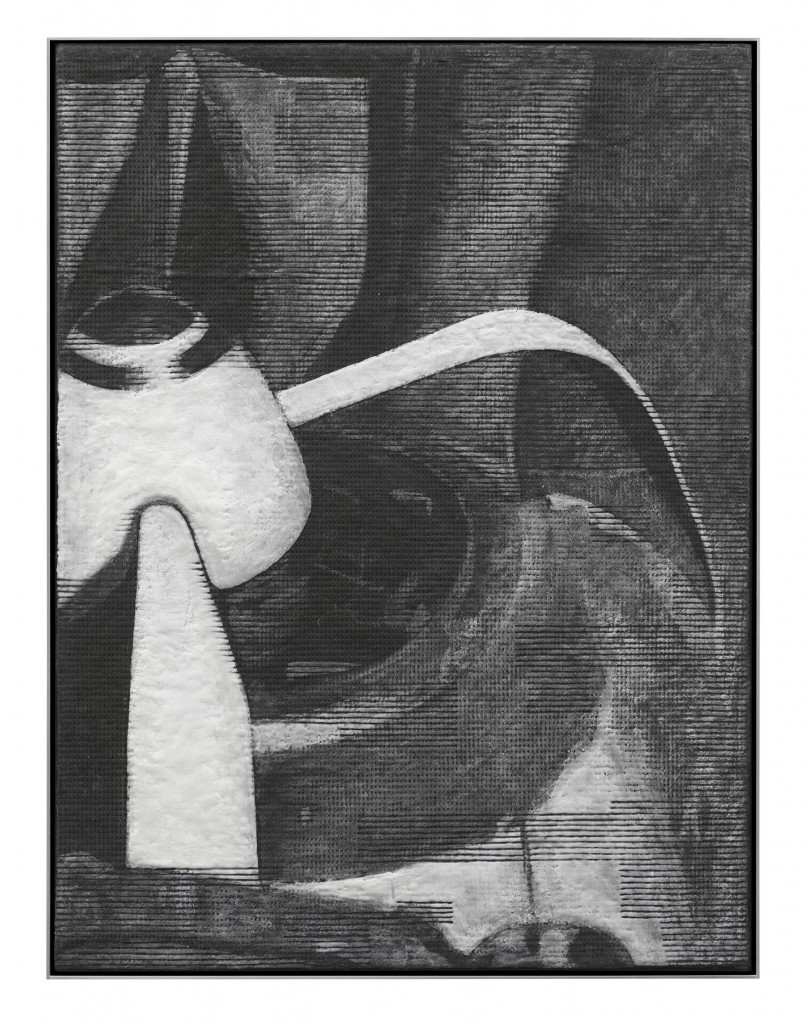

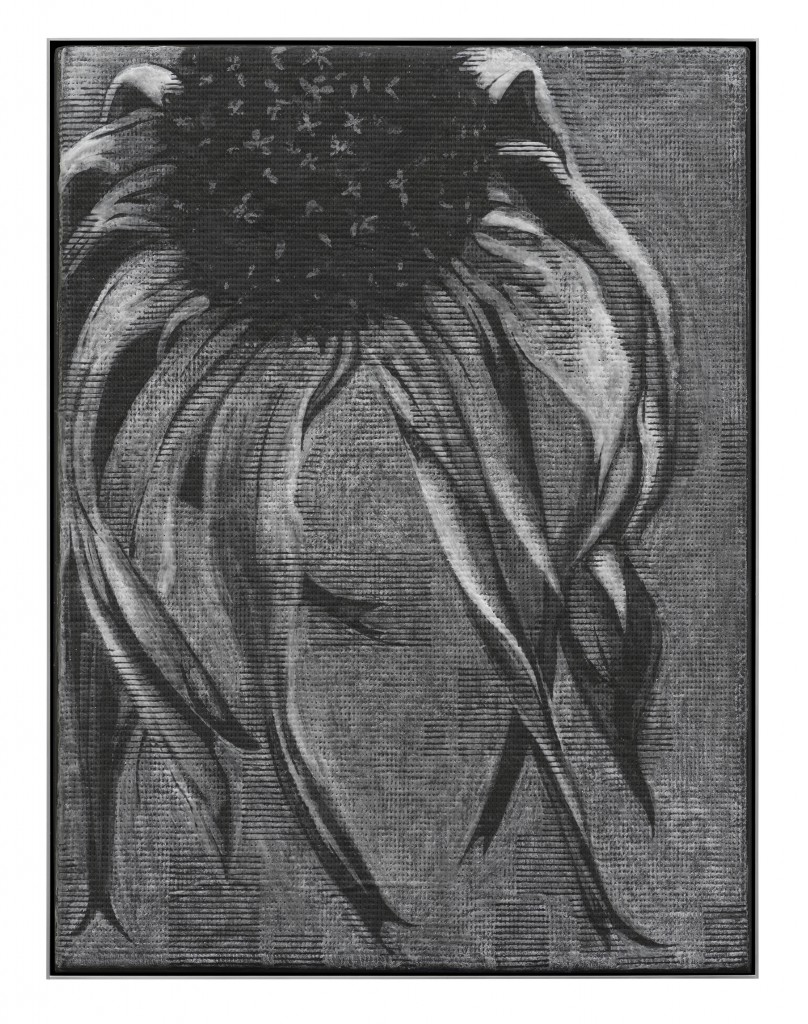

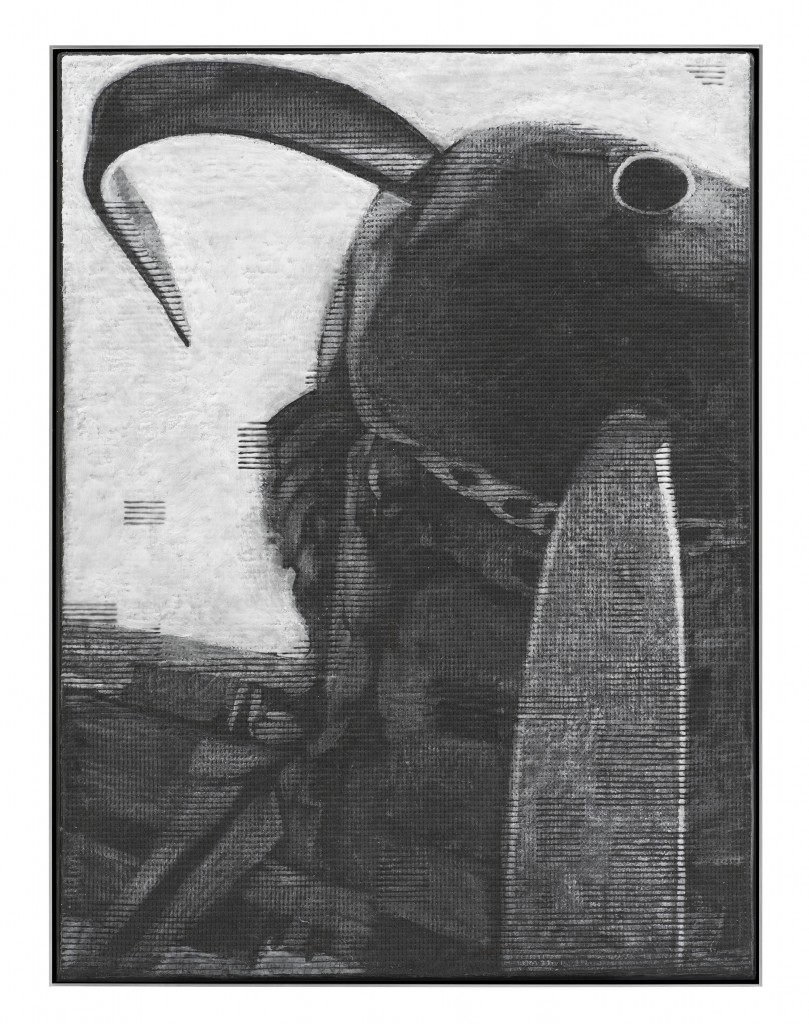

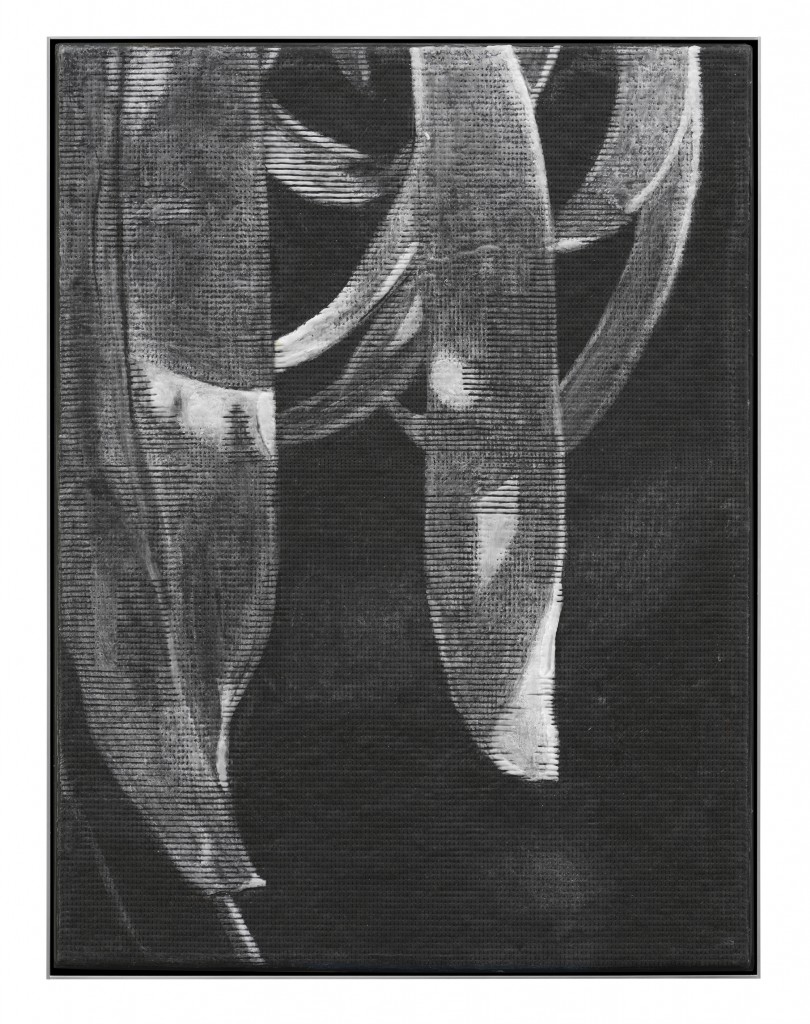

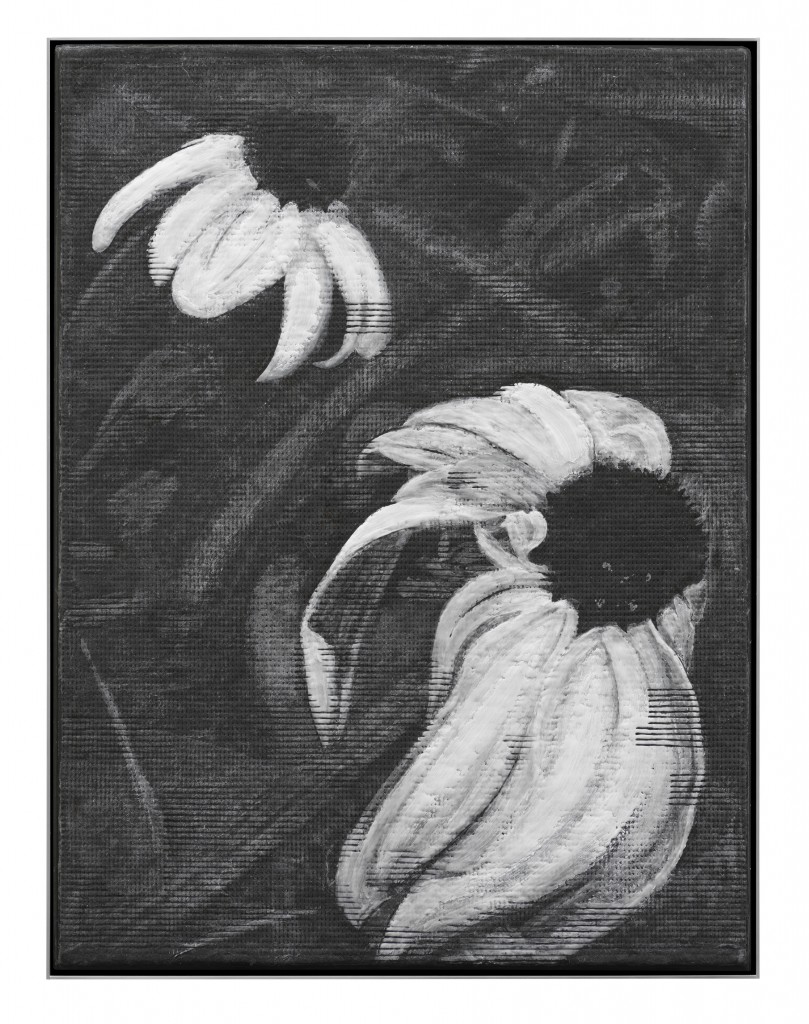

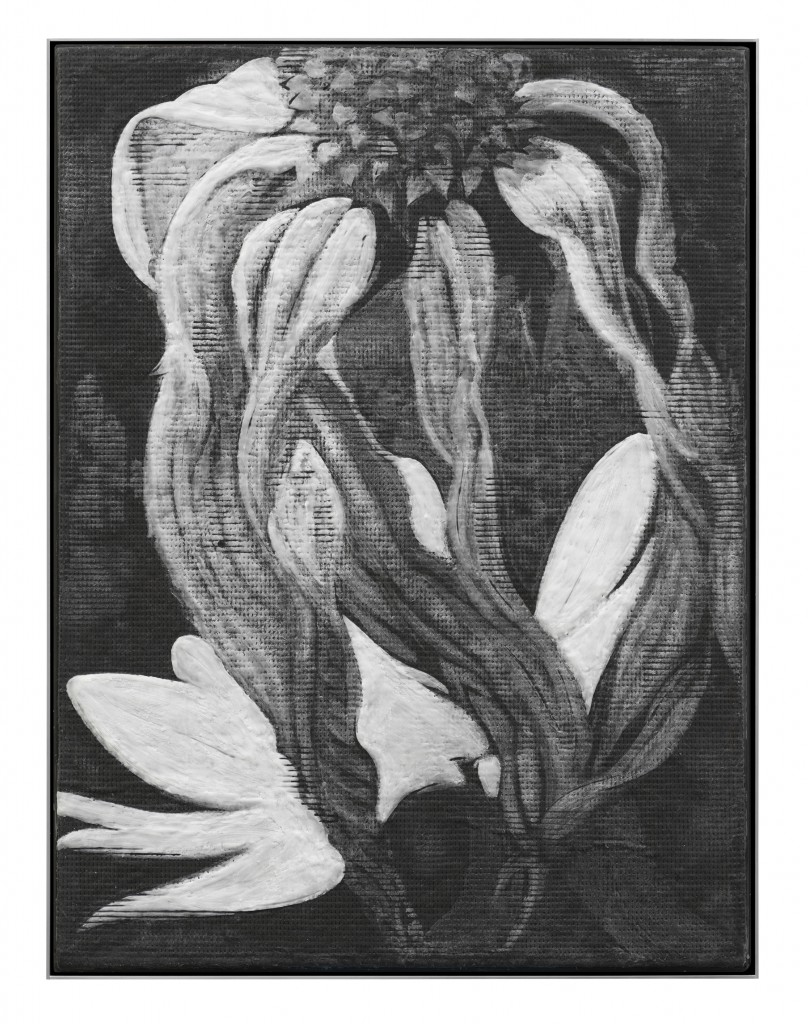

Accompanying the sculptures is a series of paintings of wilted flowers, rendered with melted wax and heat. Based on found photographs, these works translate botanical decay into scorched, fragile surfaces.

In linking nature, technological progress, and motifs of transience, Daniel Hölzl develops a contemporary form of poetic critique. In the propeller, past inventive spirit merges with the vision of a more environmentally friendly, electronic aviation technology of the future. His new works are not nostalgic machine fragments but markers of the present, reminding us that progress and finitude are inextricably intertwined, and that we live amid this very ambivalence.

The above is an excerpt from an essay on the exhibition by Madeleine Freund that will be published on our website prior to the opening.

Also during Berlin Art Week, Daniel Hölzl’s solo installation soft cycles is on view at Berlinische Galerie. And with support from Berlinische Galerie, Hölzl and Abie Franklin present a new site-specific installation titled Bycatch as part of the group exhibition HALLEN 06 at Wilhelm Hallen (Kopenhagener Str. 60–68, Berlin), on view September 6–14, 2025.

For further information on the artist and the works or to request images, please contact Owen Clements, owen@dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM sind stolz, PROPEL, Daniel Hölzls zweite Einzelausstellung in der Galerie, zu präsentieren. Die Schau eröffnet während der Berlin Art Week am Donnerstag, den 11.9.2025, 18–22 Uhr im Rahmen der Gallery Night und ist bis zum 25.10.2025 zu sehen. Der Künstler vertieft darin seine materiellen und konzeptuellen Forschungen zu Transformationskreisläufen, industriellem Gedächtnis und der Poetik des Antriebs – Themen, die er 2022 in seiner Einzelausstellung GROUNDED vorgestellt hat.

Hölzls disziplinenübergreifende Praxis ist von einer feinfühligen, aber kritischen Auseinandersetzung mit den das moderne Leben prägenden Systemen und Materialien gekennzeichnet. In einer Verbindung von skulpturaler Ingenieursarbeit und Vergänglichkeit erkundet seine Kunst die ineinander verwobenen Lebenszyklen von Luftfahrt, Energie und Umweltbewusstsein.

Im Mittelpunkt von PROPEL stehen drei Typen von Propellern; in einer tiefgründigen Reflexion auf Bewegung, technologischen Fortschritt, Zusammenbruch und Verwandlung lassen sie die Formen von Samen und Bombe, Ursprung und Ende erahnen.

Der erste, der auf einem historischen Sternmotor aus einem „Rosinenbomber“ sitzt, hat verformte Aluminiumflügel, die über den Boden streichen, halb flugfähig, halb schon abgestürzt. In der Mitte des Galerieraums drehen sich derweil drei hohle Kohlefaserpropeller über den Köpfen der Besucher*innen in einer kinetischen Installation, von der Tropfen aus recycelter Luftverschmutzung hergestellter schwarzer Tinte in weitem Bogen gegen die Wände fliegen und so nach und nach eine durchgehende Linie zeichnen. Die dritte, in Paraffinwachs gegossene Gruppe hat sich unter Sonneneinstrahlung verformt und hebt und senkt sich mit der Umgebungstemperatur, worin die Entropie von Technologie wie Natur anklingt.

Begleitet werden die Skulpturen von einer Reihe von Bildern verwelkter Blumen, die aus geschmolzenem Wachs unter Hitzeeinwirkung entstanden sind. Die auf gefundenen Fotografien basierenden Arbeiten übersetzen botanischen Verfall in versengte und empfindliche Oberflächen.

In der Verknüpfung von Natur, technischem Fortschritt und Vergänglichkeitsmotiven entwickelt Daniel Hölzl eine zeitgenössische Form poetischer Kritik. Im Propeller vereinen sich vergangener Erfindergeist und die Vision einer umweltfreundlicheren, elektronischen Luftfahrttechnik der Zukunft. Seine neuen Werke sind keine nostalgischen Maschinenfragmente, sondern Marker einer Gegenwart, die daran erinnern, dass Fortschritt und Endlichkeit untrennbar miteinander verwoben sind und dass wir inmitten dieser Ambivalenz leben.

Das Obige ist ein Auszug aus einem Essay von Madeleine Freund zur Ausstellung, der vor der Eröffnung auf unserer Website veröffentlicht wird.

Ebenfalls während der Berlin Art Week ist Daniel Hölzls Solo-Installation soft cycles auf der Berlinischen Galerie zu sehen. Und mit Unterstützung der Berlinischen Galerie zeigen Hölzl und Abie Franklin vom 6. bis zum 14.9. eine neue ortsspezifische Installation mit dem Titel Bycatch im Rahmen der Gruppenausstellung HALLEN 06 in den Wilhelm Hallen (Kopenhagener Str. 60–68, Berlin).

Für weitere Informationen zum Künstler und den Werken oder um Bilder anzufordern, wenden Sie sich bitten an Owen Clements, owen@dittrich-schlechtriem.com.