Othering is alterity in the active voice—the often violent process of designating a body as alien, which frequently precedes and accompanies social exclusion. It is the declaration that you are not me and, because of that, do not share access to the rights that I possess. Othering is me saying that you belong to the margins—social, legal, often architectural—while I, to the center. But othering is also the necessary precondition for any politics, whether good or bad. In a famous passage from the Phenomenology of the Spirit, Hegel narrates an encounter between two beings who each approach the other as an object, only to realize they both possess self-consciousness. This recognition appears as a threat. On approaching the other, self-consciousness “has lost itself, for it finds itself as an other being,” Hegel describes.[1] The encounter precipitates a “struggle to the death,” culminating in the enslavement of one by the other. But this resolution doesn’t hold. The enslaved is forced to recognize the slaver on pain of death, while the slaver becomes dependent on the labor of the person they enslaved, without producing anything meaningful themselves. True self-consciousness requires mutual, interpersonal recognition—liberation of the other proves a necessity if I am to be free.

A century and a half later, in the aftermath of the Shoah, Emmanuel Levinas develops a philosophy that also begins with meeting the other. Like Hegel, Levinas marks this moment—the face-to-face encounter—as a foundational phenomenon for consciousness. But rather than privileging violent reactions, Levinas emphasizes an experience of responsibility. “The Other precisely reveals himself in his alterity not in a shock negating the I, but as the primordial phenomenon of gentleness,” he writes.[2] Encountering the face of another makes a demand of me that precedes my capacity to affirm or deny their being and their worth. For Levinas this is a transcendental experience—almost holy. Everything hinges on my response. The possibility of hospitality is predicated on the unexpected arrival of the stranger; only through choosing to rename them as my guest can I assume the identity of a welcoming host. Ethics emerge on this threshold and, from it, all else: without the other, there is no self.

This is as true ontologically as it is phenomenologically. Biologists use the term “microbiome” to describe the alien nature of human bodies and environments. Your gut alone contains countless microorganisms: bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea. Some of these creatures are pathogenic, meaning they cause disease, such as the SARS-CoV-2 virus that can induce COVID-19. Others are symbiotic, facilitating and enabling good health. According to a 2020 study published in Cureus, the relative health of your microbiome has effects that extend from the physiological to the psychological.[3] A healthy gut flora transmits brains signals that manage stress reactions, while adverse changes to gastrointestinal microbiota can precipitate depression, which in turn engenders neuroendocrine disruption. Put simply, the word “human” is a poor container, if not an outright misnomer, for the thousands of lives sheltered on and within our flesh. We are legion, literally. To forget this often proves fatal.

In medicine, “autoimmunity” refers to when an organism’s antibodies and T-cell receptors mistake healthy cells and tissues as an antigen, a foreign agent, and trigger an immune response. In effect, the body attacks itself while attempting to protect itself, mistaking the self for the other, as if a case of mistaken identity leading to friendly fire. Autoimmune diseases often emerge spontaneously and randomly, but research indicates that many of our best laid schemes to eradicate health risks in our environments, from hand sanitizer to antimicrobial soaps, go often awry, whether leading directly to increased allergies, autoimmune disorders, or the emergence of antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.”[4] Autoimmunity, in conceptual terms at least, is not strictly physiological and automatic, but extends into social relations.

In an interview with Giovanna Borradori published in 2003, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida recoups the term as a political metaphor to make sense of the events of September 11, 2001.[5] Explicating the post-Soviet global order as structurally tethered to the United States, he describes a body politic that supersedes the borders of individual nation-states, even as it often acts to shore them up. Unlike the wars of previous centuries featuring distinct and opposing sides, the attacks on the World Trade Center seemed to him to come from within: the perpetrators coopted American machines to attack American buildings through American airports. Successors to the mujahideen funded and trained by the U.S., their opposition to the United States emerged, in large part, from American imperialist aggression in the Middle East and its support for Saudi Arabia during the First Gulf War. In turn, the response by the U.S. and its NATO allies—the “global war on terror”—definitionally implicated the entire planet as a potential battlefield. This promise was quickly made real, as the U.S. extended the scope of its response far from any meaningful relation to the perpetrators of the attacks, often infringing on the sovereignty of other states in the process. Within this limitless, endless, and ambiguous conflict, distinctions between ally and enemy, civilian and combatant, quickly blurred. The consequences of this continue to unfold some twenty years later, producing further antagonisms, conflicts, and instability both abroad and within the declared territorial limits of the United States. In a globalized world, the self and other are not so easily delaminated.

At the center of the co-constituent crises that mark the contemporary—political or humanitarian, ecological or epidemiological—is an autoimmune-like relationship of othering, in which a refusal to recognize our contingent dependence on both other humans and other-than-human agents is leading to mutually assured destruction. If the representative technologies of the nineteenth century were the train and the telegram, then perhaps our era belongs to the HVAC system: in order to temporarily cool your home, you use a machine that depends on carbon-emitting electricity and raises global temperatures—a positive feedback loop inching us towards our own annihilation. The only path to survival is recognition, communication, and care across the artificial—and adverse—boundaries we’ve erected between ourselves and other beings. For many artists and theorists, this necessitates the development of novel forms of translation capable of bridging not only linguistically different human populations, but also across the gulf of anthropocentrism. Mutualism—or cooperative relations between different species—already entails informational transfer. But in order for humans to learn to live with and among the other-than-human beings that we depend on—and who depends on us—we must dismantle inherited ideologies that privilege the human, and foster the emergence of both intra- and interspecies communication tools.

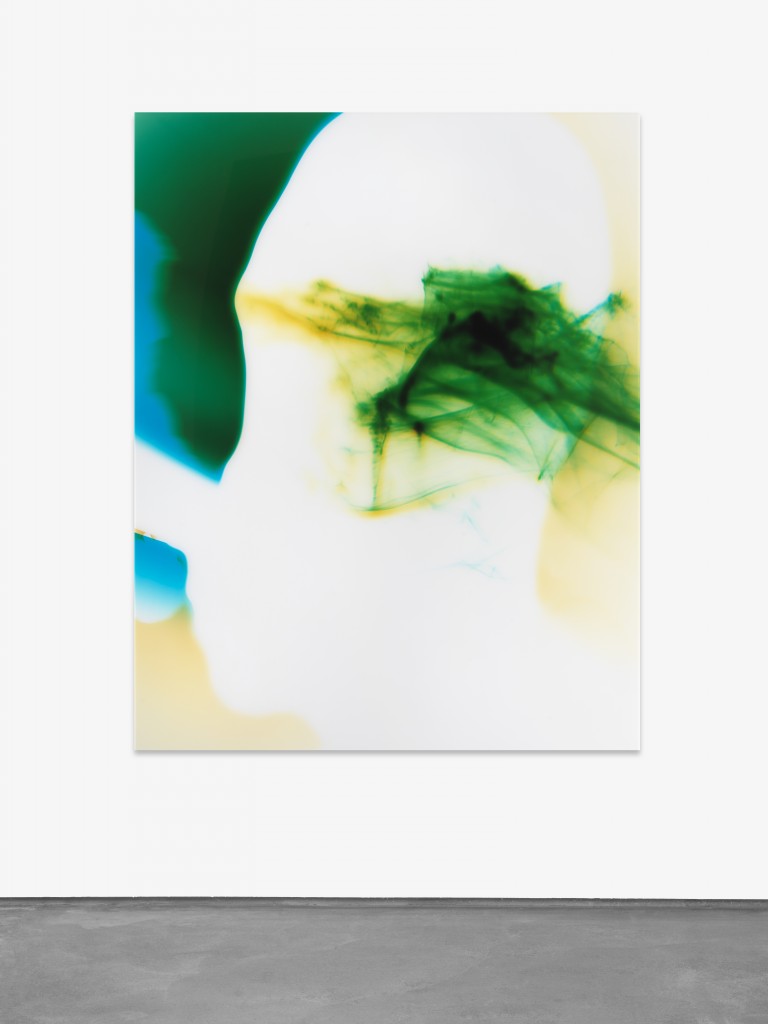

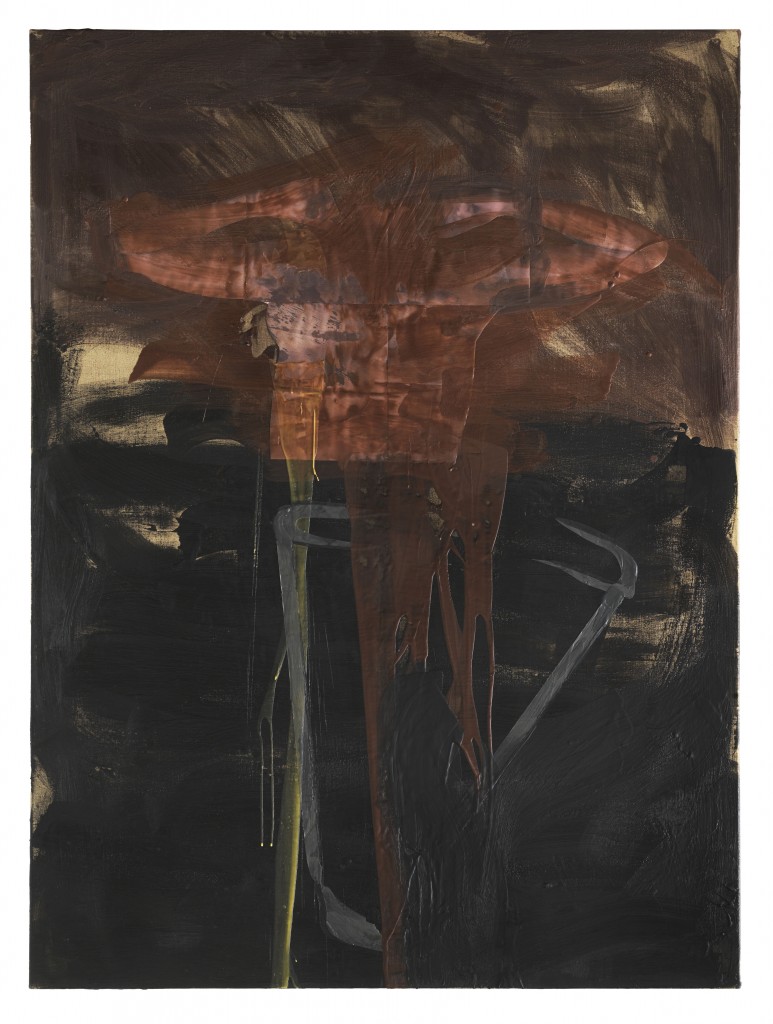

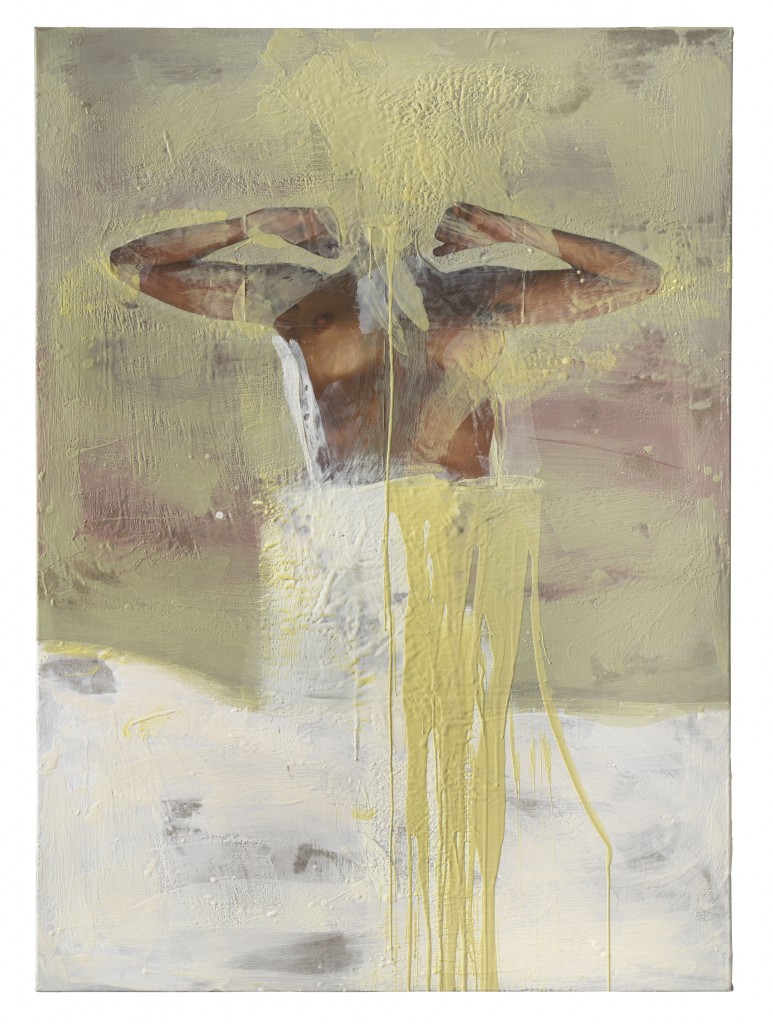

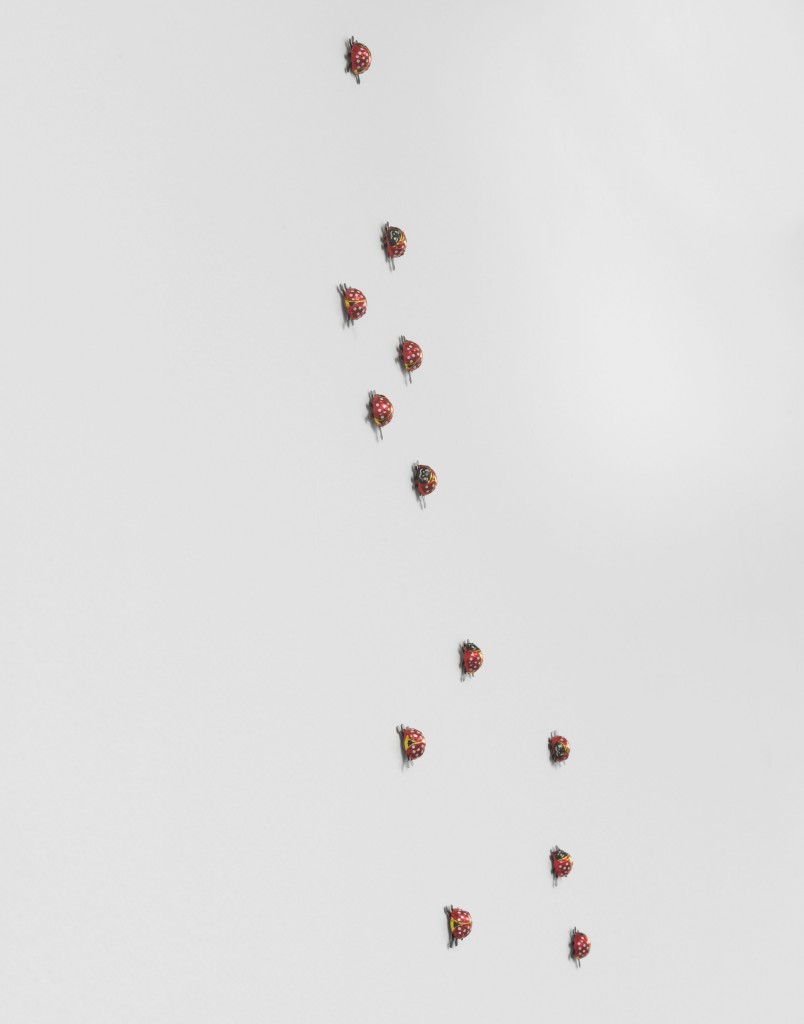

Othering is a group show curated by Jonas Wendelin opening on April 29, 2022, in conjunction with Gallery Weekend Berlin. It features the work of ten artists that explore, in various ways, how certain lives—human and nonhuman—are designated as alien, and the possibilities of forging communication, recognition, and solidarity across the yawning chasm of self and other. Filmmaker Yalda Afsah depicts complex relationships between humans and animals, merging documentary and staged choreography to explicate the blurred ambivalence between care and control that defines interspecies relations. A print by Albrecht Dürer features a rooster perched on a heraldic crest, presented in three dimensions—a prescient and surreal scramble of the animal world with its representation as image within the militaristic signifier of a coat of arms. An almost inverse view of human-animal relations can be read in a print by Francisco de Goya from his enigmatic series Los Disparates (The Follies), which depicts humans taking flight with strange, bat-like appendages. Alongside it, another print from the series depicts revelers during a carnival celebration, but with joy indiscernible from anguish and masks, from faces. Works by Andreas Greiner, meanwhile, question the art-historical tradition of landscape painting, using a Deep-Learning algorithm to produce hallucinatory and ambiguous depictions of the natural world, acting as both an extension of the human gaze as well as a refusal of its capacity to reify nature, as expressed in the Romantic sublime.

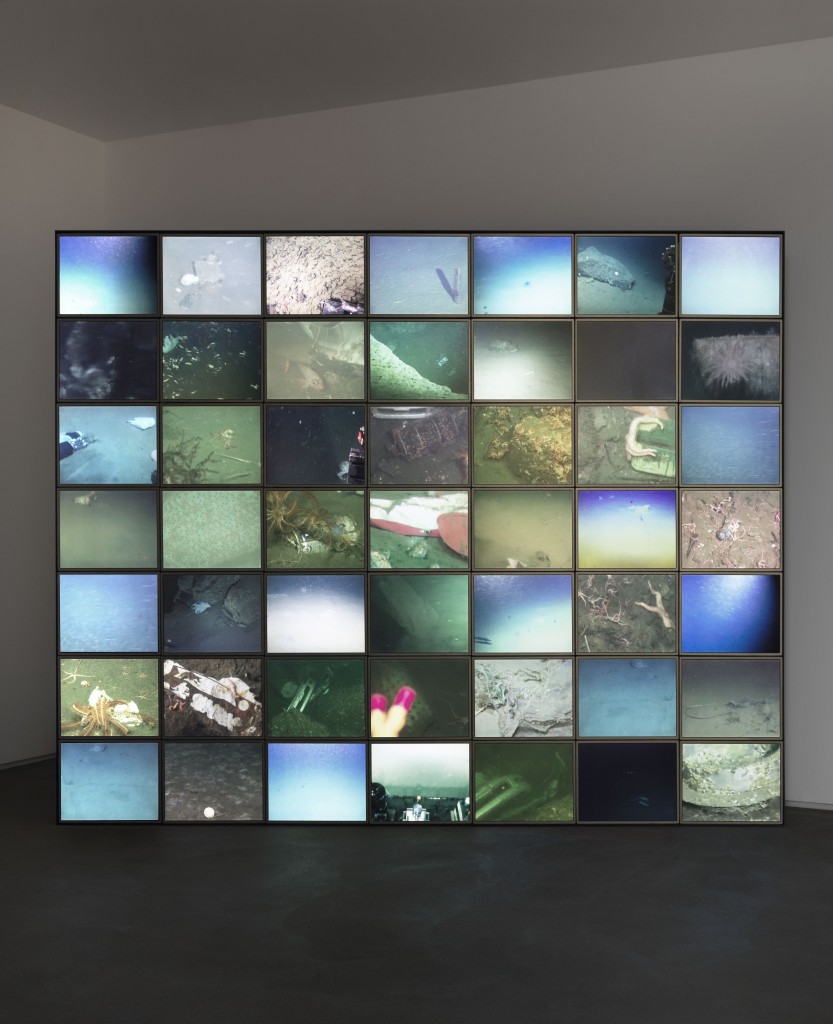

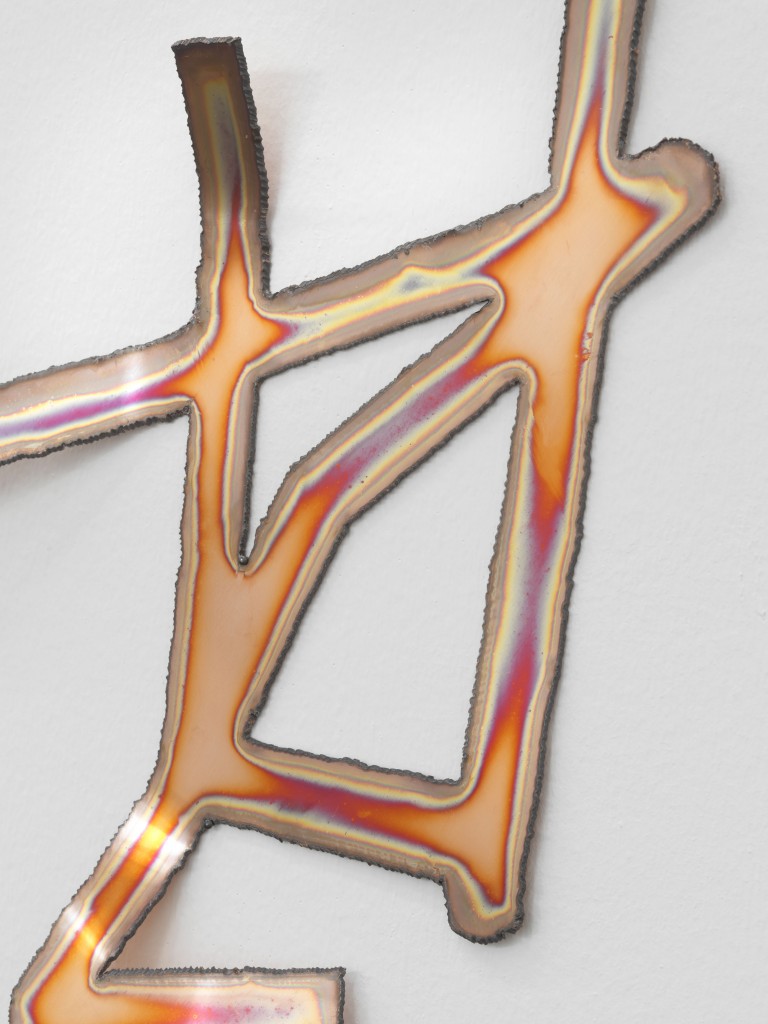

Julian Charrière’s 49-channel multimedia installation The Gods Must Be Crazy features a collection of found underwater footage presented as if a contemporary vanitas, in which the frontiers of human exploration are already littered with human waste—a submerged landscape populated by the already-present ruins of modernity. Jol Thoms addresses nature, technology, and the cosmos in his research-driven practice, experimenting with modes of sensing more-than-human and extra-planetary worlds on registers beyond the quantifiable. The work of Jenna Sutela also involves collaborations with both non-artists such as technologists and biologists and other-than-human beings such as bacteria to promote interspecies communication in opposition to anthropocentric worldviews. Analisa Teachworth likewise envisions new forms of communication in her work, using storytelling to unpack the reality-defining implications of technology on both personal terms as well as within collective histories. Meanwhile, the work of Sung Tieu contends with notions of social identity and its demarcation. It analyses the transnational movements of both people and objects—be it through the investigation of diaspora communities or the commercial, hyper-accelerated ways global capitalism is reproduced. Finally, works by Jonas Wendelin detourn Silicon Valley office aesthetics, deploying a parabolic cubicle system as a canvas for images of reptilian irises, acting as both a critique of the tech industry’s encroachments into life and work and a subversive reclamation of its forms.

[1] G.W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller with analysis of the text and foreword by J. N. Findlay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), par. 179, p. 111.

[2] E. Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969), p. 150.

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7510518/.

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/12/health/immune-system-allergies.html.

[5] Giovanna Borradori, “Autoimmunity: Real and Symbolic Suicides,” in Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jürgen Habermas and Jaques Derrida (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), pp. 85–136.

____________

Nicholas Korody is a writer, editor, and researcher from Los Angeles, currently based in Milan. He is the cofounder of Adjustments Agency and works independently as Interiors Agency. He is the author of The Uses of Decorating, a collection of four essays on the political economy of amateur home decorating, which was translated into Spanish and published in Madrid in 2020. He is currently Managing Editor of Capsule and formerly served as Editor-in-Chief of the architecture magazine Ed. His writing has been featured in publications such as 032c, Pin-Up, Harvard Design Magazine, Metropolis Magazine, Kaleidoscope, and e-flux Architecture, while his design work has been exhibited at institutions internationally, including Spazio Maiocchi in Milan, Swiss Institute in New York, Triennale di Milano, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, and Moderna Museet in Stockholm.