DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM is pleased to present the first solo show in Berlin by KEITH BOADWEE (b. 1961, Meridian, Mississippi, USA; lives and works in Emeryville, California, USA). The exhibition opens on Friday, September 16, 2022, 6–8 PM, with previews available to coincide with BERLIN ART WEEK 2022.

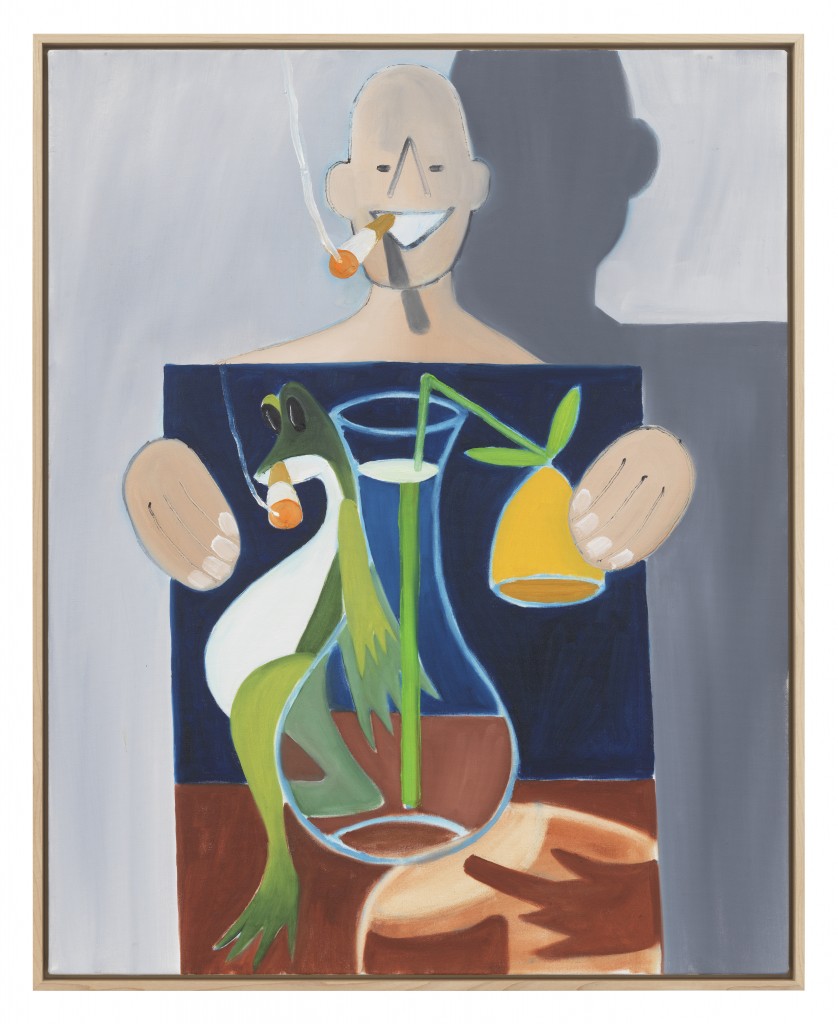

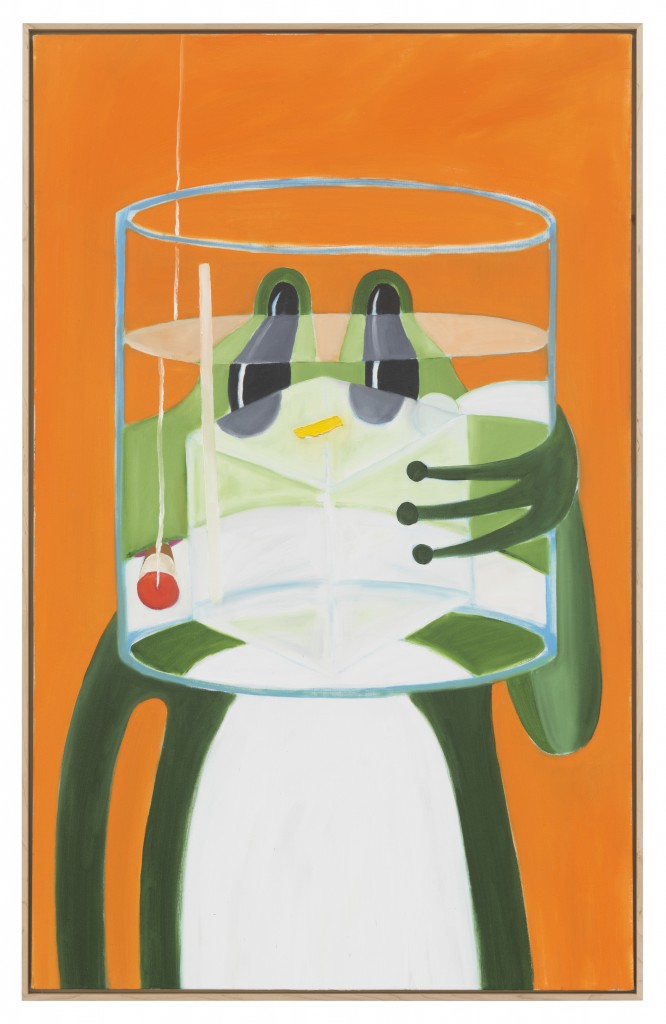

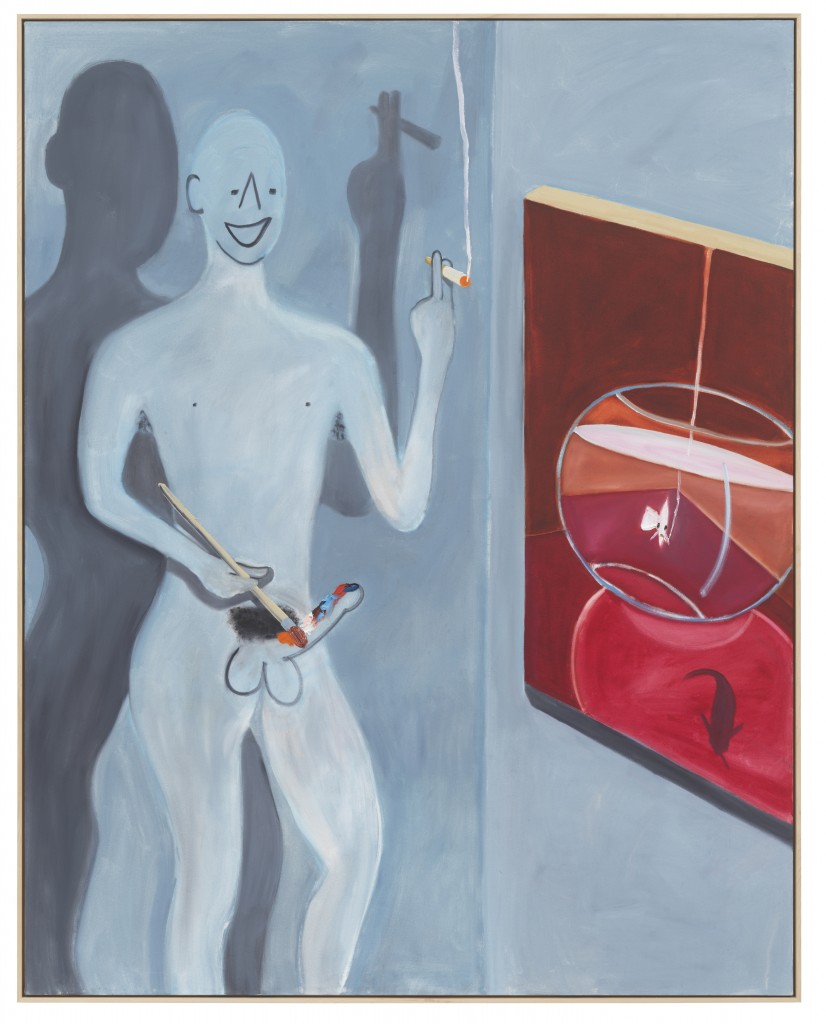

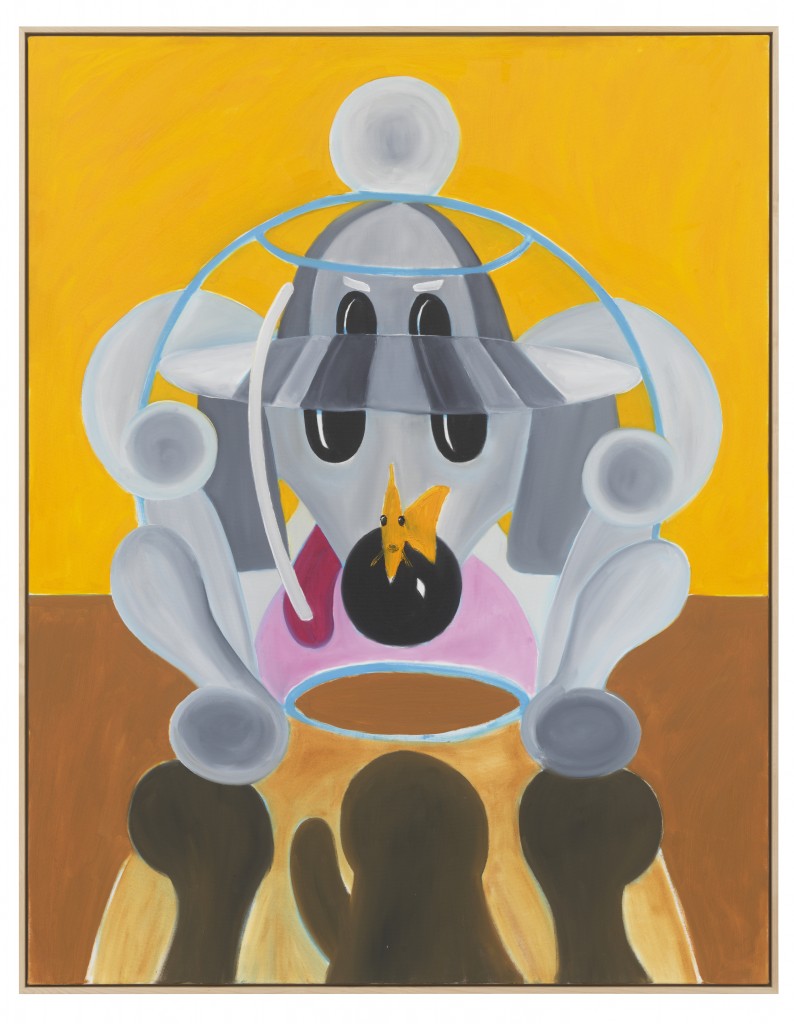

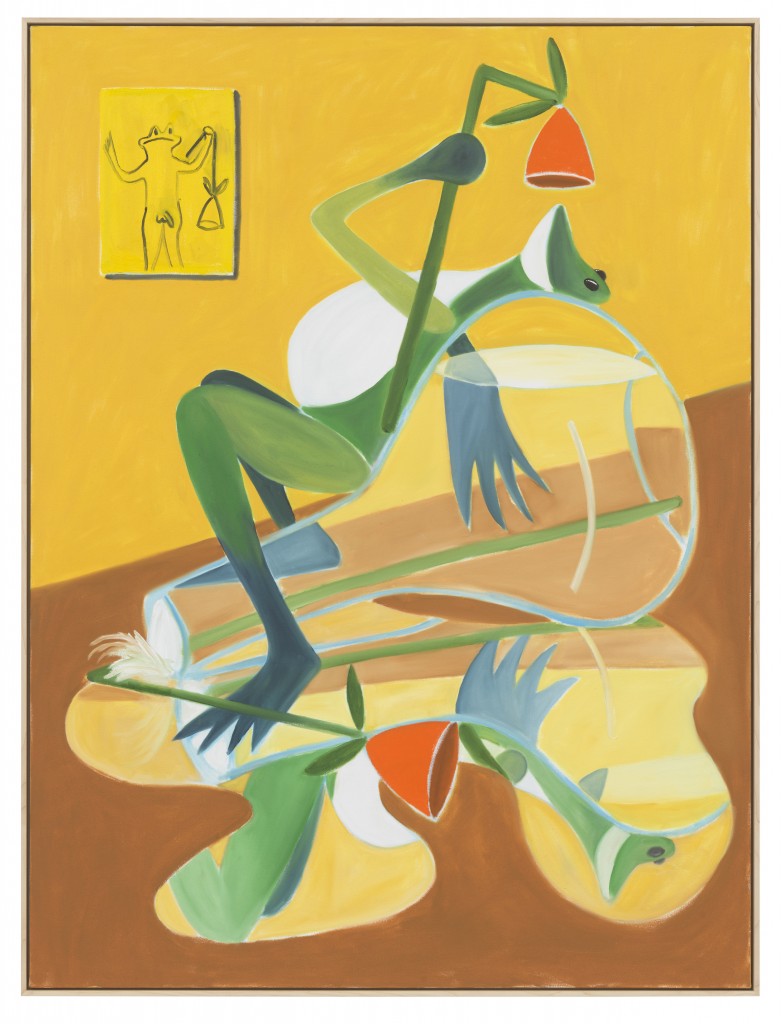

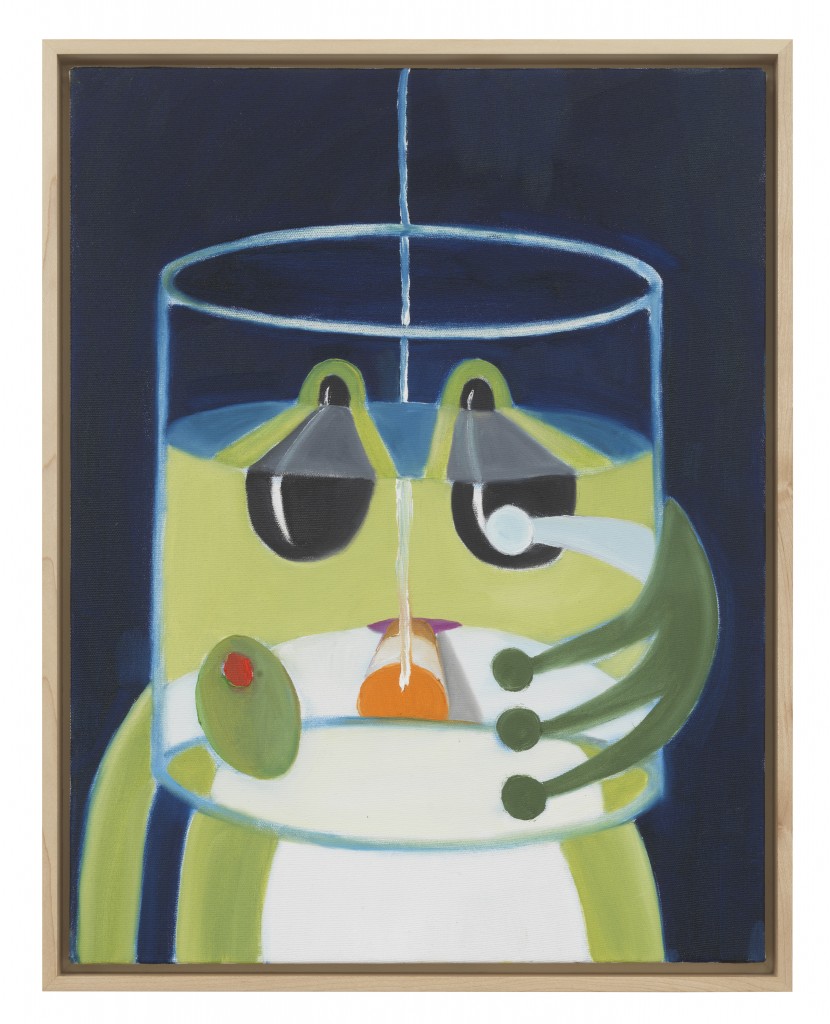

Portrait subjects -frogs, poodles, and fish- are depicted in multi-planer dimensions, posed and peering through cocktail glasses, prisms, and fish bowls, geometrically divided, multiplied and reflected. The new artworks have evolved now into a realm of spiritual abstraction. On the occasion of the exhibition, the gallery will produce and publish a catalog of the works available in September 2022. For further information on the artist and the works or to request images, please contact Owen Clements, owen(at)dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

Keith Boadwee received a Master of Fine Arts from the University of California, Berkeley, CA in 2000 and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of California, Los Angeles, CA in 1989. His work has been included in thematic exhibitions such as AA Bronson’s Garden of Earthly Delights, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg, Austria (2015); AA Bronson’s Sacre du Printemps, Grazer Kunstverein, Graz, Austria (2015); 15 Minutes of Fame: Portraits from Ansel Adams to Andy Warhol, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA (2010); Prospect 1.5, New Orleans, LA (2010); Into Me / Out of Me, MoMA PS1, Long Island, NY and KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany (2006); Grey Area, California College of Art, San Francisco, CA (2003); The People’s Plastic Princess, Banff Center, Calgary, Canada (2000); Double Trouble: The Patchett Collection, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA (1998); Selections from the Peter and Eileen Norton Collection, Santa Monica Museum of Art, Santa Monica, CA (1995); Bad Girls, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, NY (1994); Slittamenti, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy (1993); and Performance Behind the Curtain, White Columns, New York, NY.

DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM freuen sich, die erste Einzelausstellung von KEITH BOADWEE (geb. 1961, Meridian, Mississippi, USA; lebt und arbeitet in Emeryville, Kalifornien, USA) in Berlin zu präsentieren Die Ausstellung wird Freitag, den 16. September 2022, 18–20 Uhr eröffnet und ist während der BERLIN ART WEEK 2022 zur Vorbesichtigung zugänglich.

Die Porträtierten werden in vielfältigen und komplexen Dimensionen abgebildet, spähen durch Cocktailgläser, Prismen und Fischgläser, werden geometrisch geteilt, multipliziert und gespiegelt. Eine erhabene Abstraktion, die vielleicht an die Bildsprache Hilma af Klints und Agnes Peltos erinnert. Die Gegenüberstellung von kunsthistorischem Einfluss und Queerness bereichert eine neue tiefgründige Bildsprache.

Anlässlich der Ausstellung wird die Galerie einen Werkkatalog produzieren, der im September 2022 veröffentlicht wird. Für weitere Informationen zum Künstler und den Werken oder um Bildmaterial anzufordern, wenden Sie sich bitte an Owen Clements, owen(at)dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

Keith Boadwee erhielt 2000 ein MFA von der University of California, Berkeley und 1989 einen BFA von der University of California, Los Angeles. Seine Arbeiten waren in thematischen Ausstellungen zu sehen, darunter AA Bronsons Garden of Earthly Delights, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg (2015), AA Bronsons Sacre du Printemps, Grazer Kunstverein, Graz (2015), 15 Minutes of Fame: Portraits from Ansel Adams to Andy Warhol, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, Ca. (2010), Prospect 1.5, New Orleans, La. (2010); Into Me / Out of Me, MoMA PS1, Long Island, N.Y. und KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2006); Grey Area, California College of Art, San Francisco, Ca. (2003); The People’s Plastic Princess, Banff Center, Calgary, Kanada (2000); Double Trouble: The Patchett Collection, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, Ca. (1998); Selections from the Peter and Eileen Norton Collection, Santa Monica Museum of Art, Santa Monica, Ca. (1995); Bad Girls, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, N.Y. (1994); Slittamenti, Venedig-Biennale, Venedig, Italien (1993); und Performance Behind the Curtain, White Columns, New York, N.Y.