DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM is pleased to present the painter Klaus Jörres’s fourth solo show at the gallery. Titled Kleine Bilder, it opens on January 21, 2022, and will be on view through March 13.

In the practice he has built over twenty years, Jörres creates large-format acrylic paintings based on renderings and drafts exported from secondhand Mac computers, manipulating the basic visual structure of modern design, the grid.

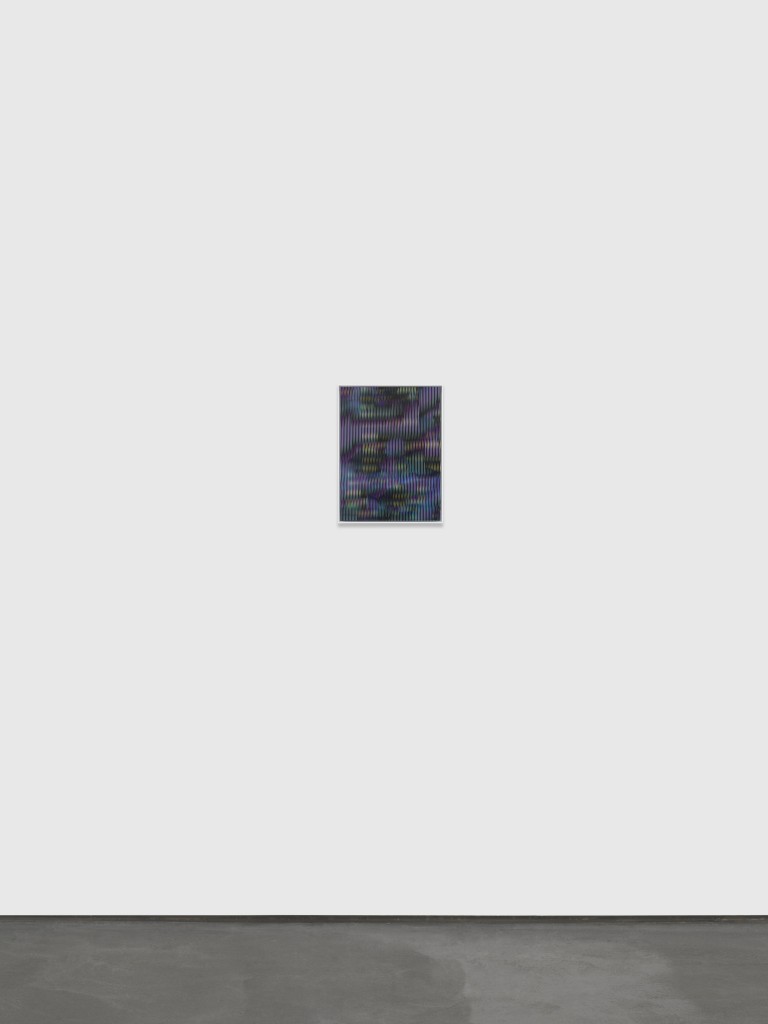

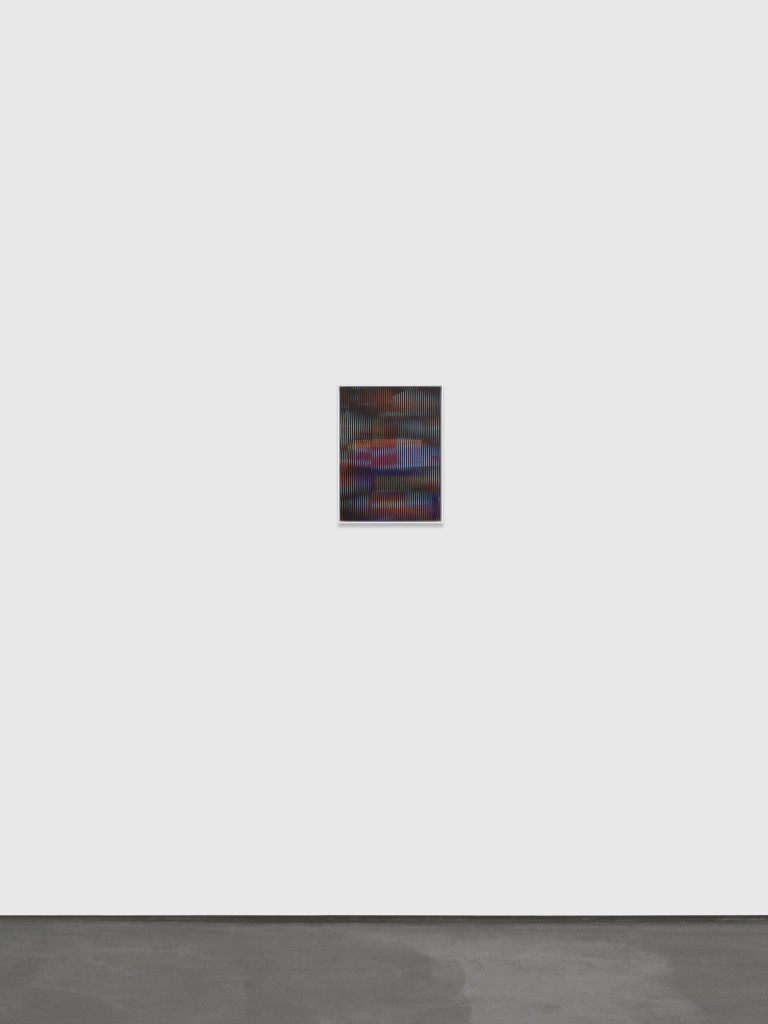

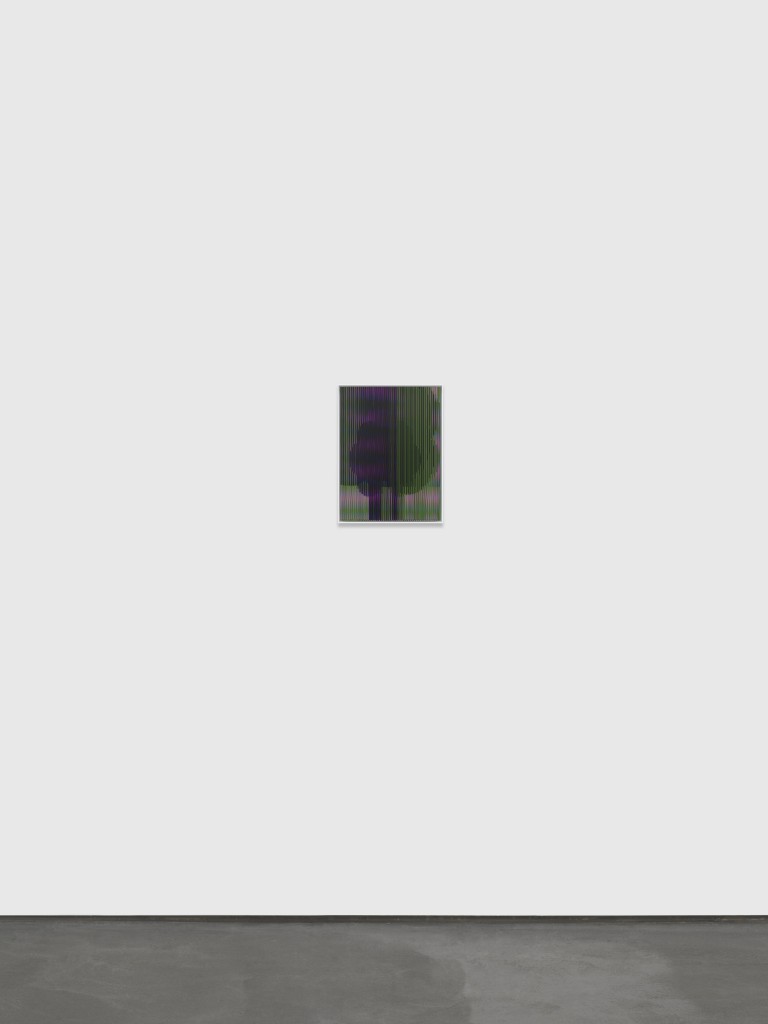

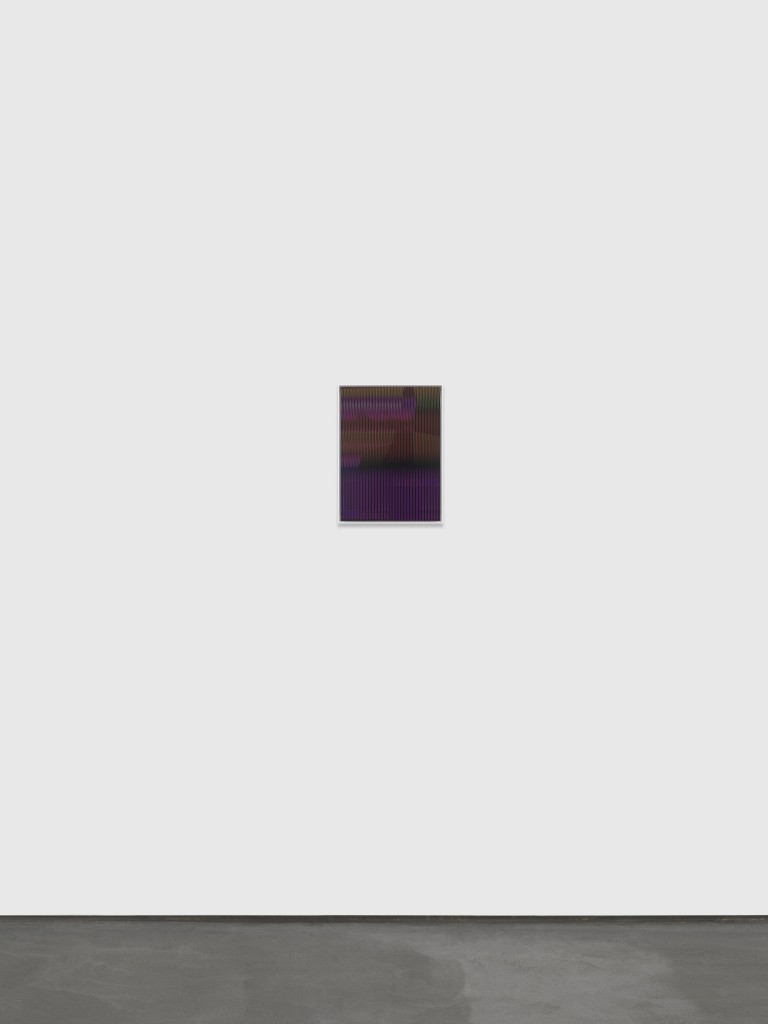

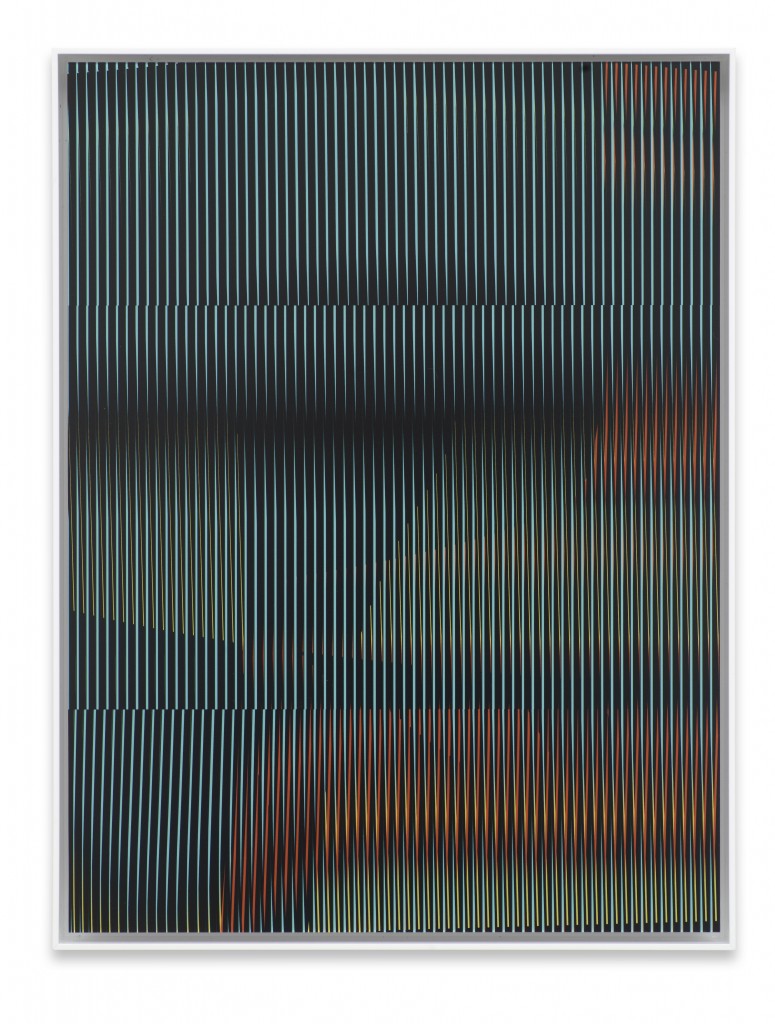

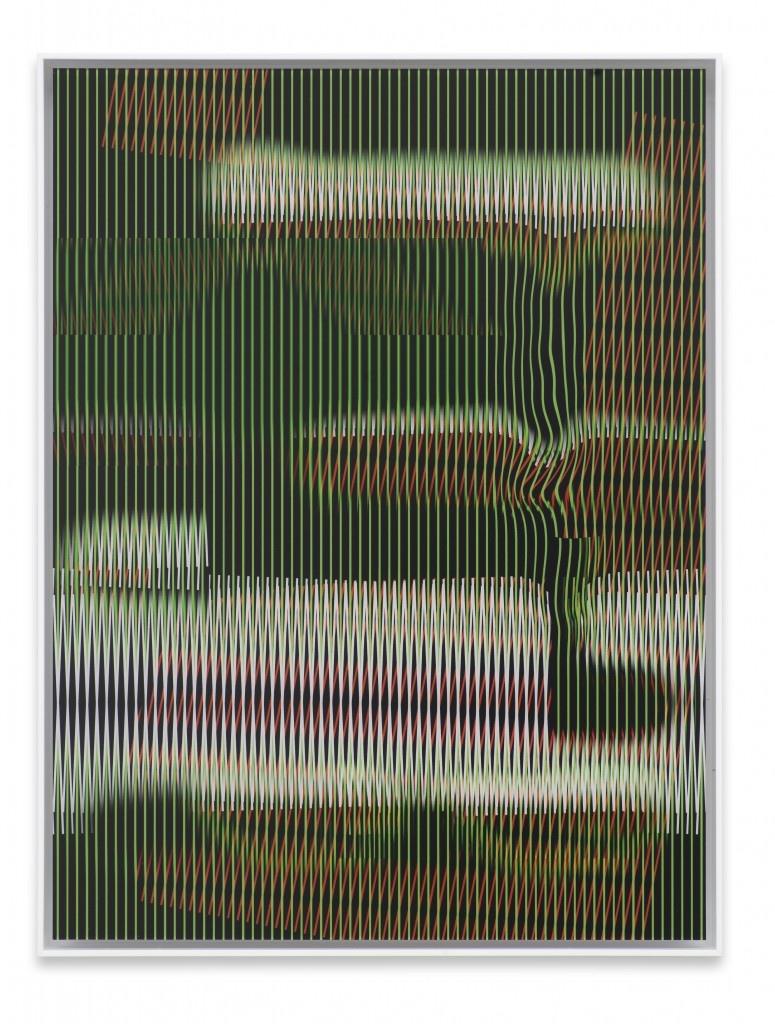

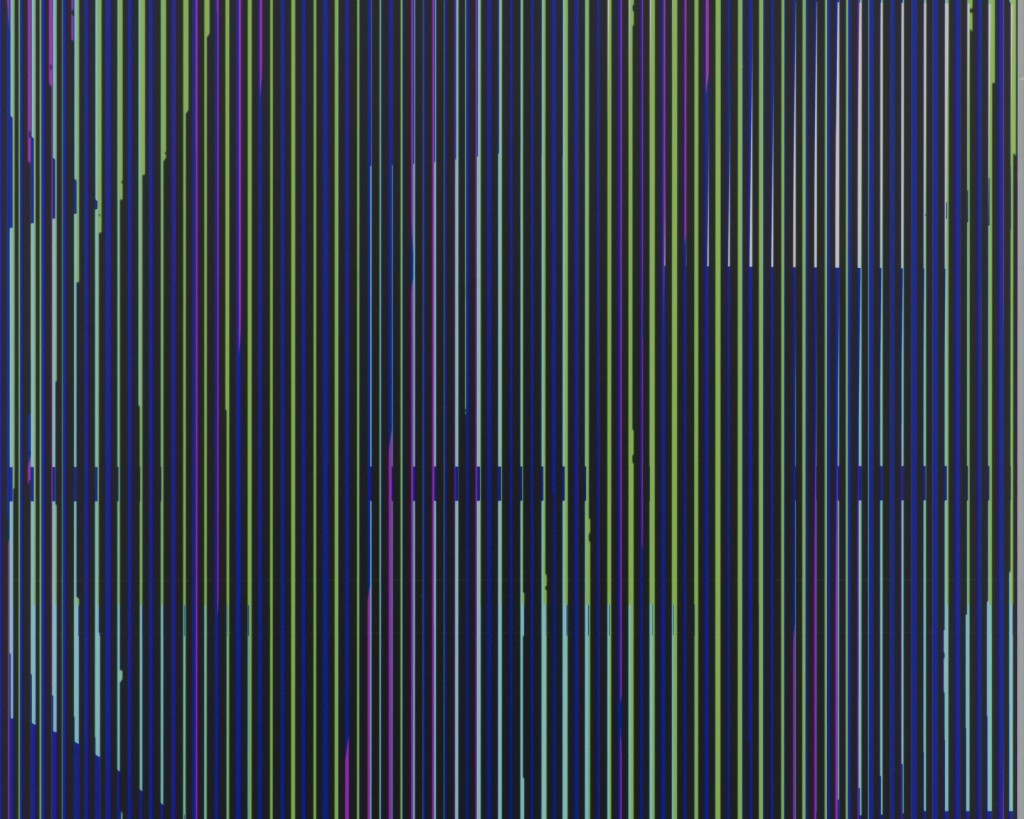

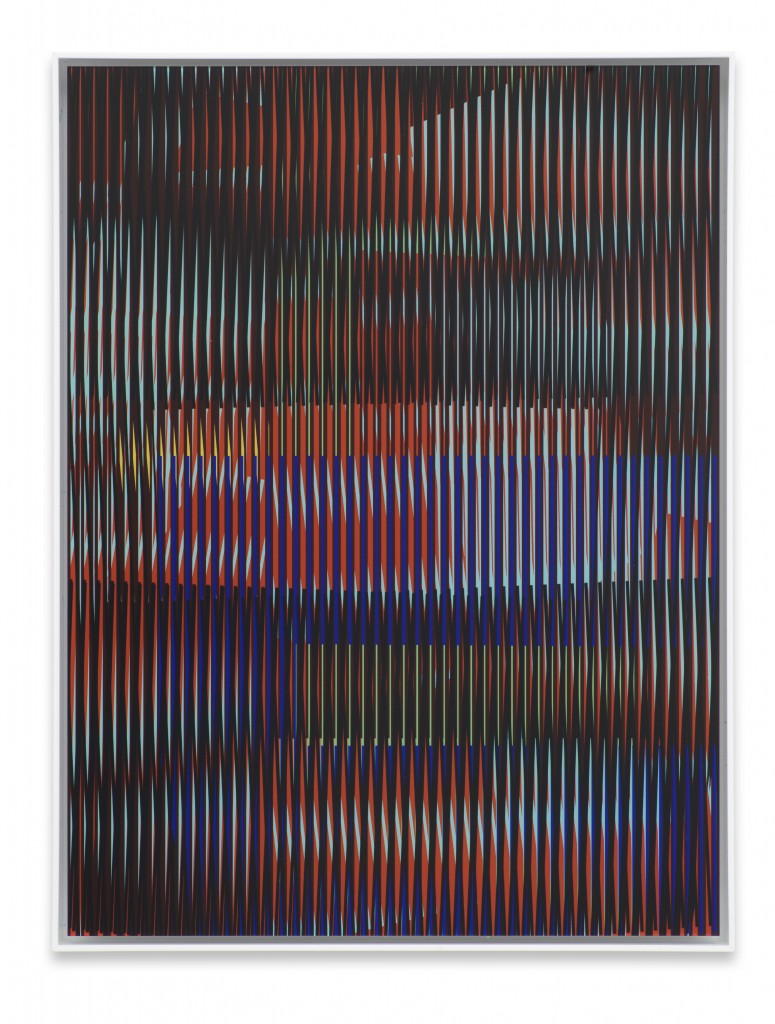

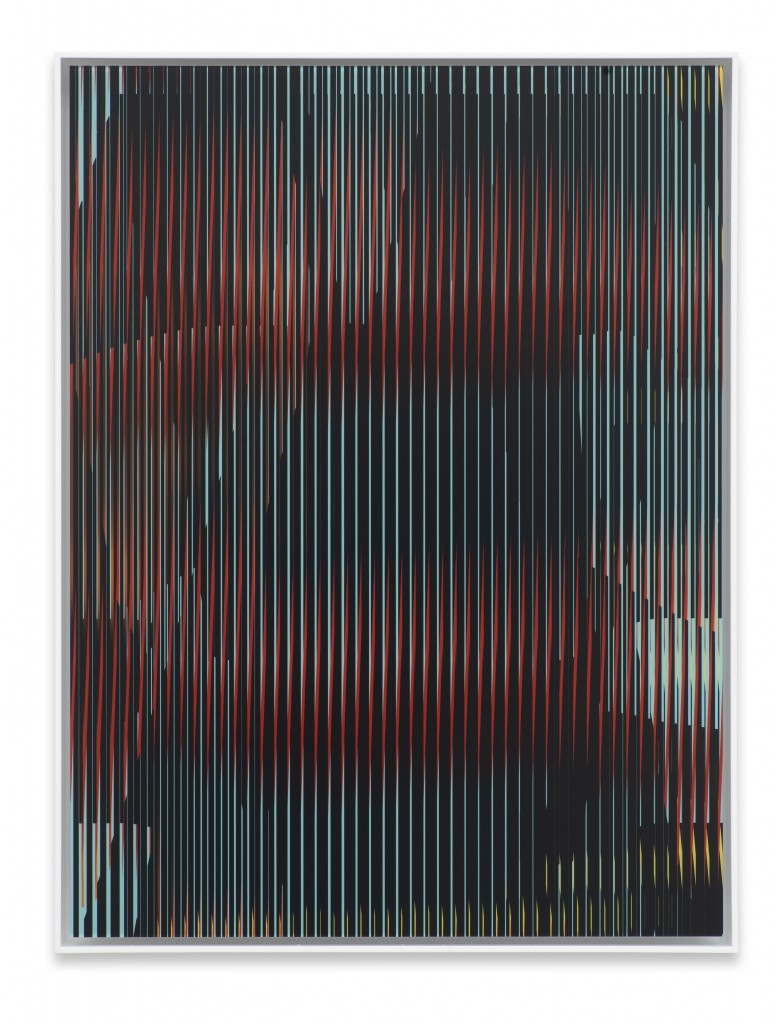

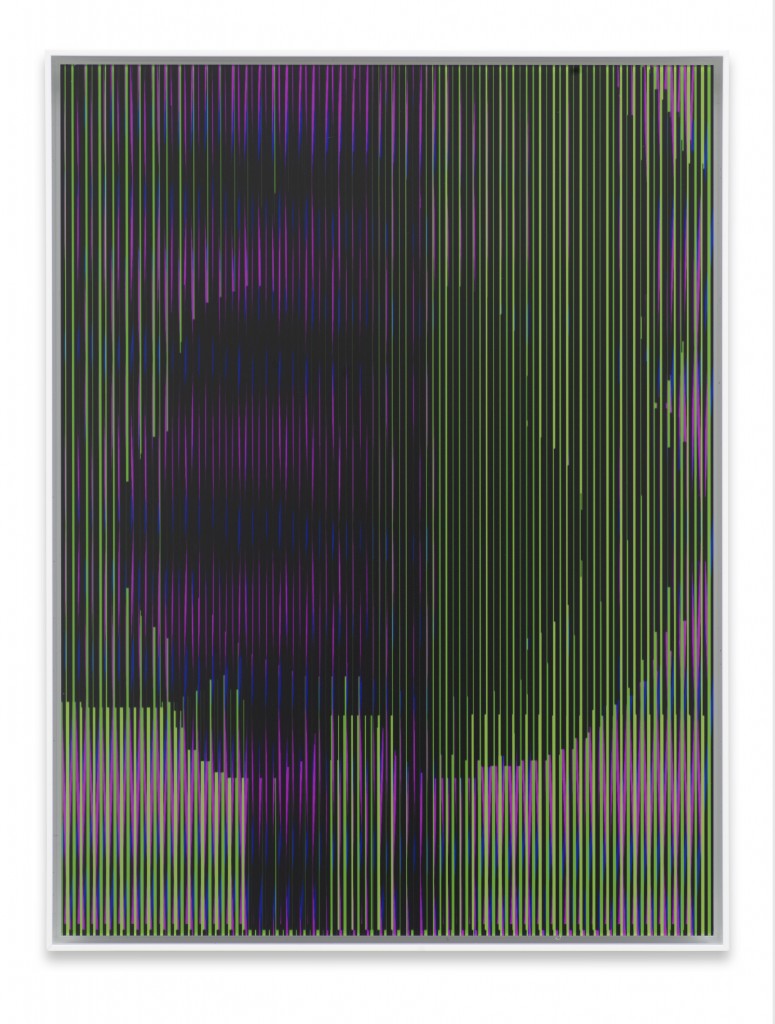

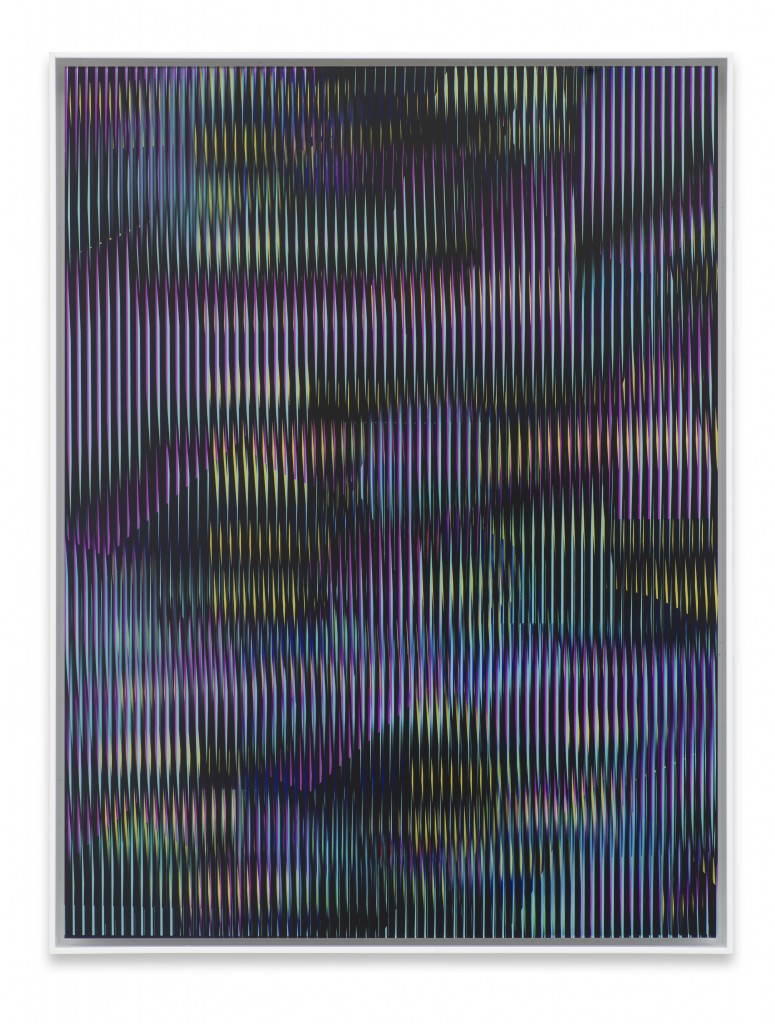

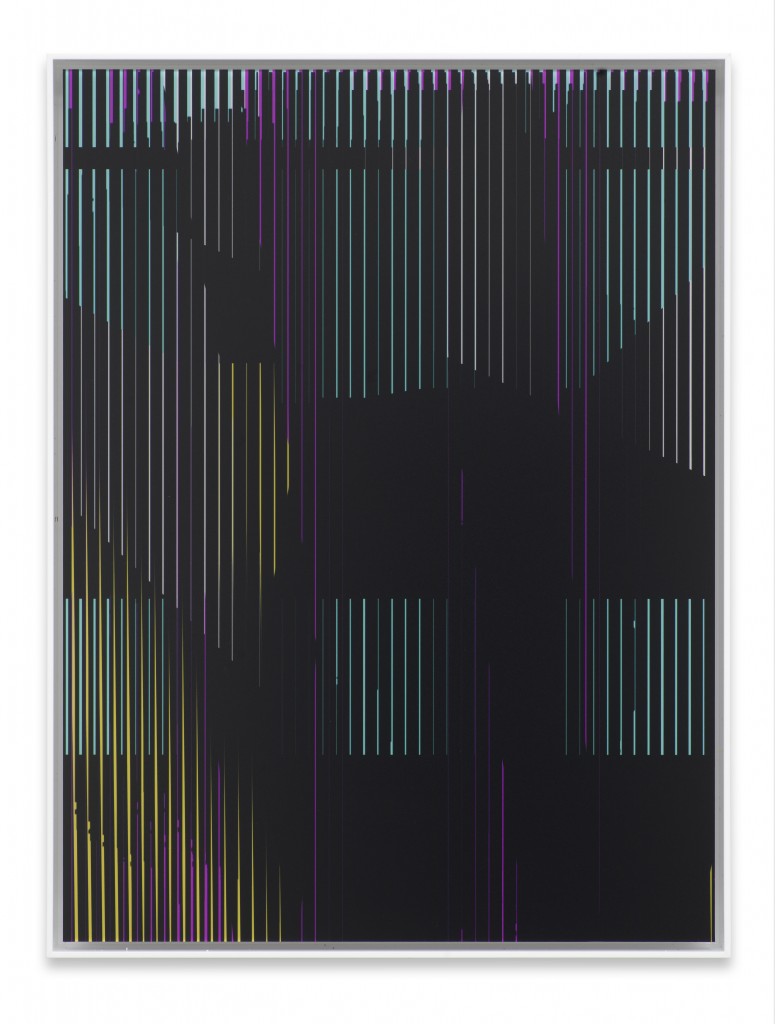

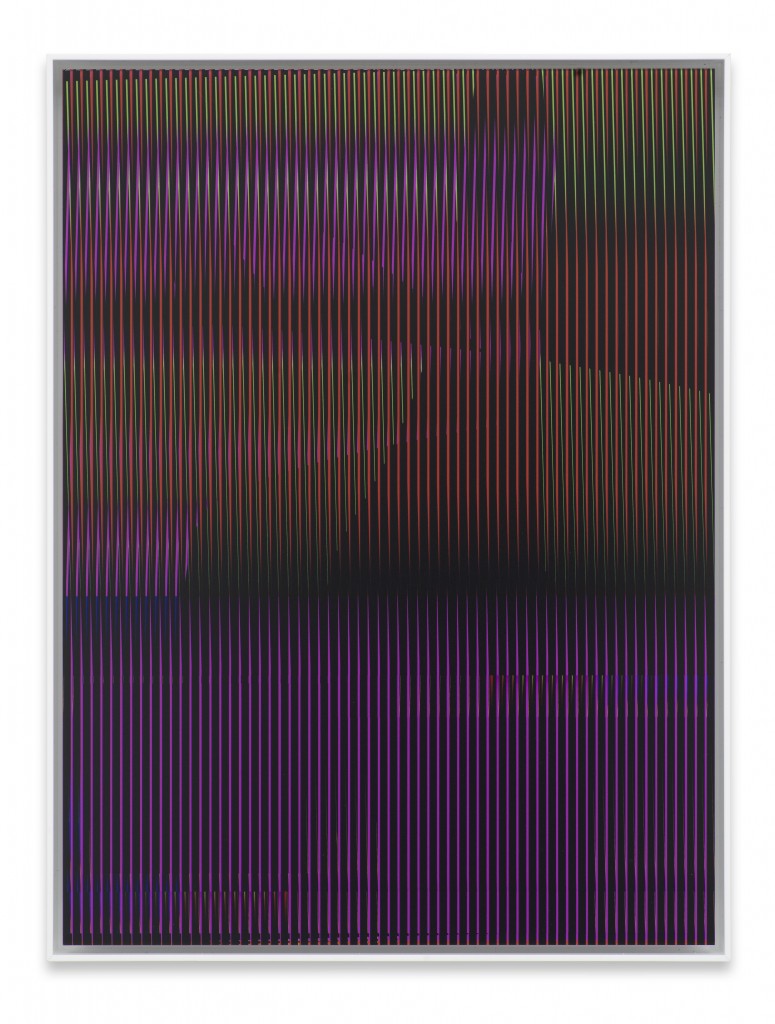

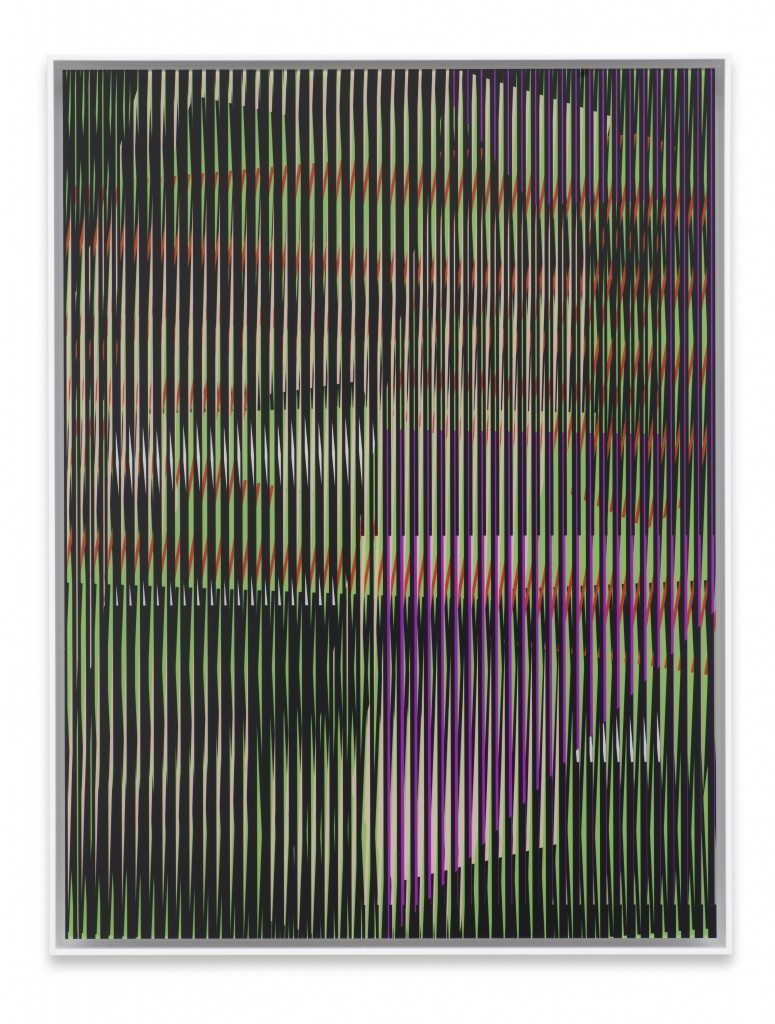

With Kleine Bilder, Small Pictures, the artist no longer transfers his “digital drafts” to the canvas by hand, instead generating a series of small-format 30-by-40-cm C-prints directly on photographic paper, framed and face-mounted to frosted acrylic glass. The cybernetic color palette and structured compositions develop images oscillating between techie disruption and classic abstraction. The acrylic front’s subtle milky thickness, not unlike the surface of oil paintings, further abstracts the linear language of rotations, overlays, repetitions, and cutouts.

Considering the long-suppressed but currently rapid rise of digital art, there exists a need for digital works of art in physical form. In this context, Jörres conceives of his Small Pictures as a tangible format that nonetheless responds to the basic ideas behind NFTs, for example, and the demands of a new kind of art market characterized by increased participation and a growing group of collectors.

To stand before an older or a more recent, a larger or smaller picture by Jörres (who has no use for work titles) is to find oneself incapable of letting one’s perceptions come to a rest. The plateaus of superimposed and intermeshed visual planes seem charged with an intangible dynamic energy that manifests as white noise and flickering. Moiré effects of the sort the artist has long employed have historic antecedents in the practices of Bridget Riley, François Morellet, or Carlos Cruz-Diez; working in different contexts, they created similar situations in the early 1960s that pushed the psycho-physiological capacity of eye and brain to edges where two-dimensional image and three-dimensional space blurred into one another. Nowadays, the ambient visual noise of Jörres’s pictures between abstraction and image interference may stand for the residual resistance that art is allowed, and by extension, for pure and positive potentiality.

Not unlike the specific objects that Donald Judd launched as vehicles of a “tactical innovatory art criticism” (Klaus Jörres) in the 1960s, deftly occupying a new interstice between painting and sculpture, the Small Pictures are specific objects: neither painting nor photography but hybrids without a central organizing principle. The artist sources all components from suppliers, making the works quasi-readymades: the demand assessment, the design and planning process, and the supply chain management are all handled from Jörres’s desk in a kind of telework, as is the final assembly of the material. It strikes me as significant that the works can’t be taken apart again. That makes them almost the physical equivalents of NFTs—simulacra. The Latin word—the Greek counterpart is “eidolon”—denotes sheer images detached from the surface, holographic “doppelgangers” of what they represent whose agency unfolds in the twilight zone between subject and object, between thing and beholder. Not coincidentally, the word “film” has its origins in a similar context. If we read Jörres’s Small Pictures as simulacra, they capture, within a world steeped in technology, the gruffly poetic quality of a new interstice bridging design and product.

The above is an excerpt from the essay contributed by Martin Germann to the catalog published on the occasion of the exhibition and available at the gallery and from our online shop this February.

Please visit our website and social media accounts for additional updates, content, and news. For further information on the artist and the works or to request images, please contact Nils Petersen, nils(at)dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM freuen sich, die vierte Einzelausstellung des Malers Klaus Jörres in der Galerie zu präsentieren. Die Schau mit dem Titel Kleine Bilder eröffnet am 21. Januar 2022 und ist bis zum 13. März zu sehen.

In seiner über 20 Jahre entwickelten malerischen Praxis schafft Jörres großformatige Acrylbilder auf Grundlage von Renderings und Entwürfen, die er aus Secondhand-Macs exportiert, um die visuelle Grundstruktur des modernen Designs, das Raster, künstlerisch zu verarbeiten.

In Kleine Bilder überträgt der Künstler seine „digitalen Entwürfe“ nicht mehr von Hand auf die Leinwand. Stattdessen entsteht die Serie von C-Prints im kleinen Format von 30 mal 40 cm direkt auf dem Fotopapier, das gerahmt und mit der bedruckten Seite auf mattes Acrylglas aufgebracht wird. Die Cyber-Farbpalette und die strukturierten

Kompositionen entfalten Bilder, die zwischen Tech-Bildstörung und klassischer Abstraktion oszillieren. Die subtile milchige Massivität der Acrylglasscheibe bewirkt ähnlich wie die Oberflächen von Ölgemälden eine zusätzliche Abstraktion der Bildsprache aus Drehungen, Überlagerungen, Wiederholungen und Ausschnitten. Der lange verdrängte, nunmehr aber um so rasantere Aufstieg digitaler Kunst weckt das Bedürfnis nach digitalen Werken in materiell greifbarer Form. In diesem Zusammenhang sieht Jörres seine Kleinen Bilder als sinnlich erfahrbares Format, das dennoch die Grundideen, die etwa hinter NFTs stehen, und die Anforderungen des heutigen durch neue Käuferschichten und eine wachsende Zahl von Sammlern geprägten Kunstmarkts aufnimmt.

Vor einem älteren wie vor einem neueren, einem größeren oder kleineren, stets nüchtern unbetitelten Jörres-Bild zu stehen bedeutet, die Wahrnehmung nicht stillstehen lassen zu können. Die Plateaus übereinander gelegter, ineinander verhakter Bildebenen scheinen mit ungreifbarer, Rauschen und Flimmern verursachender Dynamik geladen. Moiré-Effekte, wie der Künstler sie schon lange einsetzt, sind geschichtlich etwa über die Praxis von Bridget Riley, François Morellet oder auch Carlos Cruz-Diez bekannt, die in den frühen 1960er Jahren in je unterschiedlichen Kontexten ähnliche, die psycho-physiologische Kapazität von Auge und Gehirn in Grenzgebiete zerrende Situationen schufen, in denen zweidimensionales Bild und dreidimensionaler Raum fließend ineinander übergingen. Heute mag das Grundrauschen der Jörres-Bilder zwischen Abstraktion und Bildstörung für den Restwiderstand stehen, der Kunst eingeräumt wird, und damit gleichsam für reine wie positive Potenzialität.

Ähnlich wie Donald Judds spezifische Objekte, die in den 1960er Jahren als „taktische innovatorische Kunstkritik“ (Klaus Jörres) einen neuen Zwischenraum zwischen Malerei und Skulptur besetzen konnten, sind auch Kleine Bilder spezifische Objekte: weder Malerei noch Fotografie, sondern dezentral organisierte Hybride. Alle Bestandteile der Werke bezieht der Künstler als Quasi-Readymades über seine Zulieferer – Bedarfsermittlung, Entwurf, Planung und Supply-Chain Management werden allesamt in einer Art Teleworking von Jörres’ Arbeitsplatz vollzogen, genau wie die finale Assemblage des Materials. Mir scheint wichtig zu erwähnen, dass die Werke nicht mehr demontierbar sind. So sind sie beinahe physische Entsprechungen von NFTs – Simulacren. Das lateinische Wort – das griechische Gegenstück ist „Eidolon“ – bezeichnet von der Oberfläche gelöste, hauchdünne Abbilder, holografische „Doppelgänger“ des Bildgegenstandes, die ihre Wirkung in der Dämmerzone zwischen Subjekt und Objekt, Ding und Rezipient entfalten. Nicht von ungefähr entstammt auch der Begriff „Film“ ursprünglich einem solchen Zusammenhang. Verstehen wir Jörres’ Kleine Bilder als Simulacren, so machen sie innerhalb einer komplett technisierten Welt einen neuen, Entwurf und Produkt überbrückenden Zwischenraum mitsamt dessen spröder Poesie sichtbar.

Diese Passage stammt aus Martin Germanns Essay im Katalog zur Ausstellung, der im Februar in der Galerie und über unseren Online-Shop erhältlich sein wird.

Bitte besuchen Sie unsere Webseite und folgen Sie uns in den sozialen Medien, um über das Galerieprogramm und aktuelle Inhalte auf dem Laufenden zu bleiben. Für weitere Informationen zum Künstler und den Werken oder um Bildmaterial anzufordern, wenden Sie sich bitte an Nils Petersen, nils(at)dittrich-schlechtriem.com.