His epochs are not hollow similes of cultural or art history. His present is the Holocene. The Holocene is the most recent period in the earth’s history, and continues today. In the hierarchy of chronostratigraphic units, it is ranked as a series, but it is not further subdivided into stages. The Holocene began around 11,700 years ago, when a warming global climate marked the end of the Pleistocene. Holocene and Pleistocene are parts of the Quaternary, which is the youngest system of the Cenozoic. Occasionally, the Holocene is simply called the Present.

The term Holocene is Greek in origin and means “entirely new” (from oλος, “whole” or “entire,” and καινός, “new” or “recent”). The French zoologist Paul Gervais coined it around 1867/1869. A generation earlier, in 1833, Charles Lyell had proposed the term Present to denote the same period of the earth’s history. Advocates of Holocene rather than Present prevailed at the Third International Geological Congress in London in 1885.

Speculative realists such as Quentin Meillassoux fashion meticulously polished, highly exclusive, and ultimately circular theoretical zircons in the attempt to think their way into the Mariana Trenches of the non-human—and in the end remain human, all too human. Julian Charrière, by contrast, is an explorer—rather than a “researcher,” one who searches-again and produces what he hunts for—reporting from the inferno of information.

I. The Divine Commodities

Before me nothing but eternal things

Were made, and I endure eternally.

Abandon every hope, who enter here.

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia (1307–1321): Inferno, third canto Inscription on the Gates of Hell

I’m gonna put on a iron shirt, and chase the devil out of earth

I’m gonna send him to outa space, to find another race.

The Prodigy, Out of Space (1992)

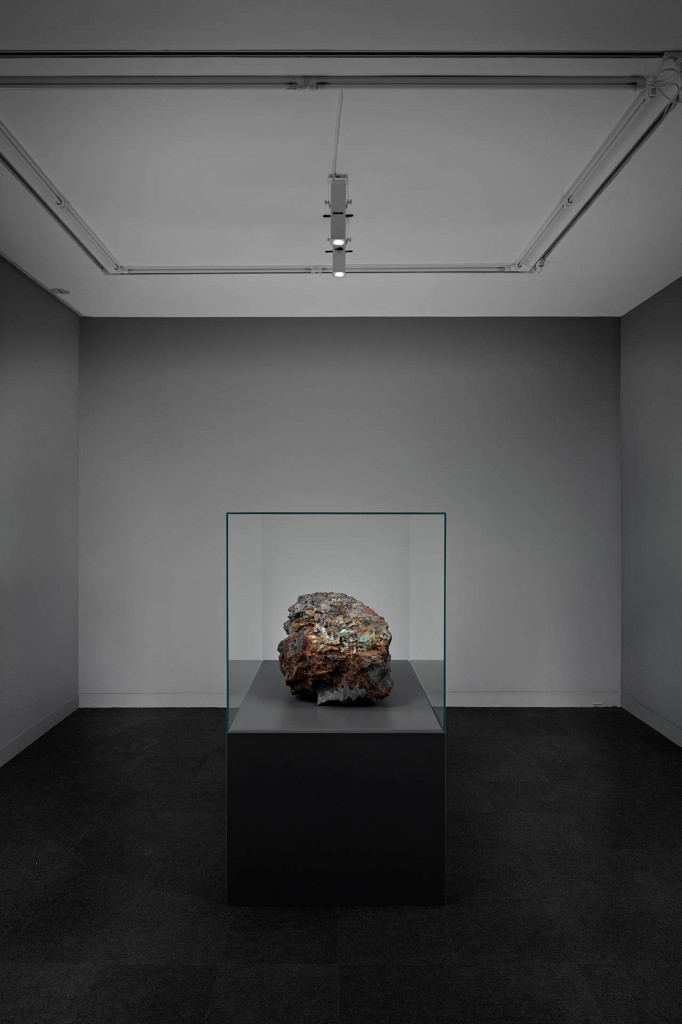

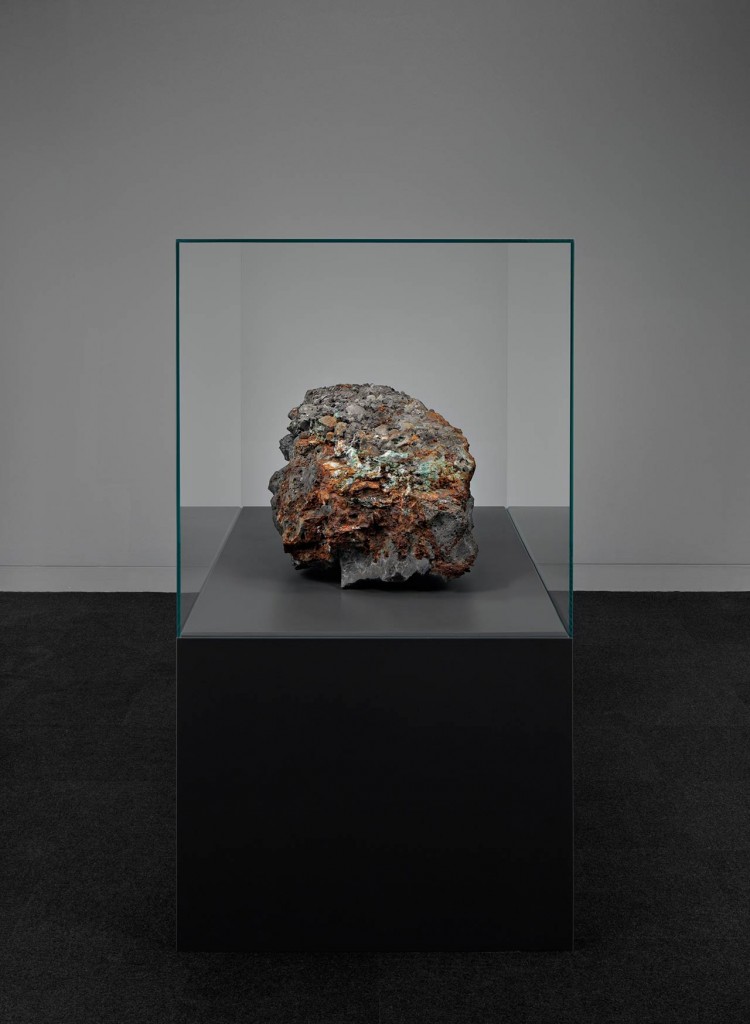

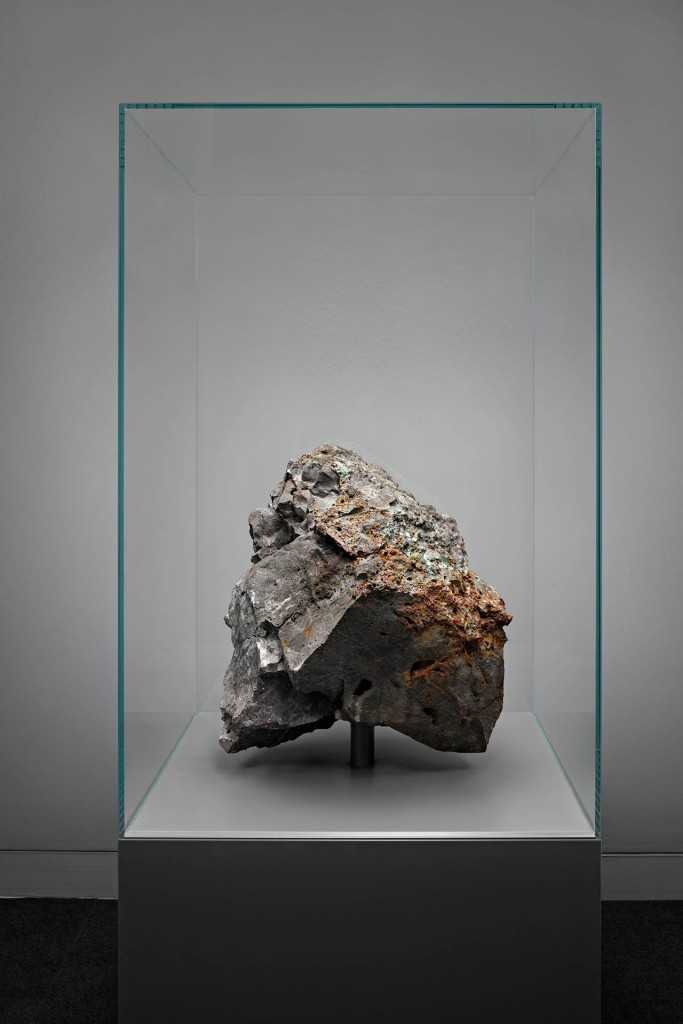

The pragmagical does not thunder in the canon of cannons, it leads an ephemeral and forever transmuting existence in the magma of the volcanoes. Where Dante, following Virgil’s guidance—“It is another path that you must take […] if you would leave this savage wilderness”—descends into the psychogeography of the Divine Comedy to wander through Inferno and Purgatorio toward Paradiso, Julian Charrière, in Into the Hollow, steers the opposite course, starting with what we might call our divine commodities and perambulating the half life of a “wastewilderness” to smelt it down in the toxic cauldron of deep time.

Dante’s topology—the crater or vortex opening onto the infinitely interior—is the eschatological bomb crater that resulted when Lucifer fell from heaven and smashed into the earth. On the opposite side of the globe, the repercussions of the impact raised the so-called mountain of purgatory, with paradise at its summit. Charrière’s information inferno, by contrast, is not an event but a state of being, permanent, distributed, veining the planet as the pits where rare earths are mined and the infrastructures they sustain:

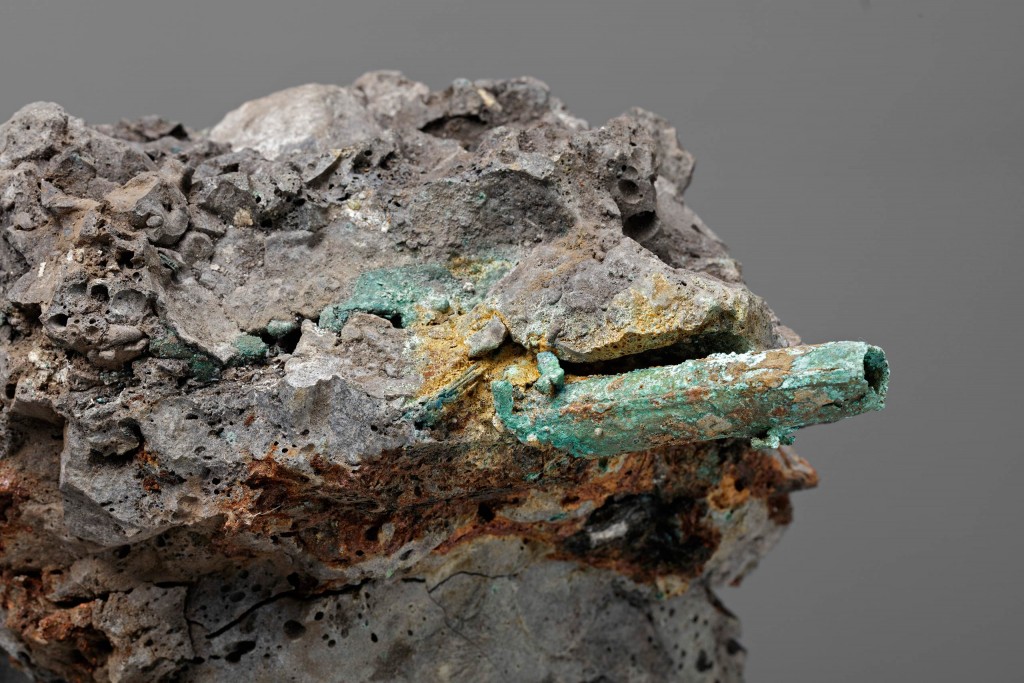

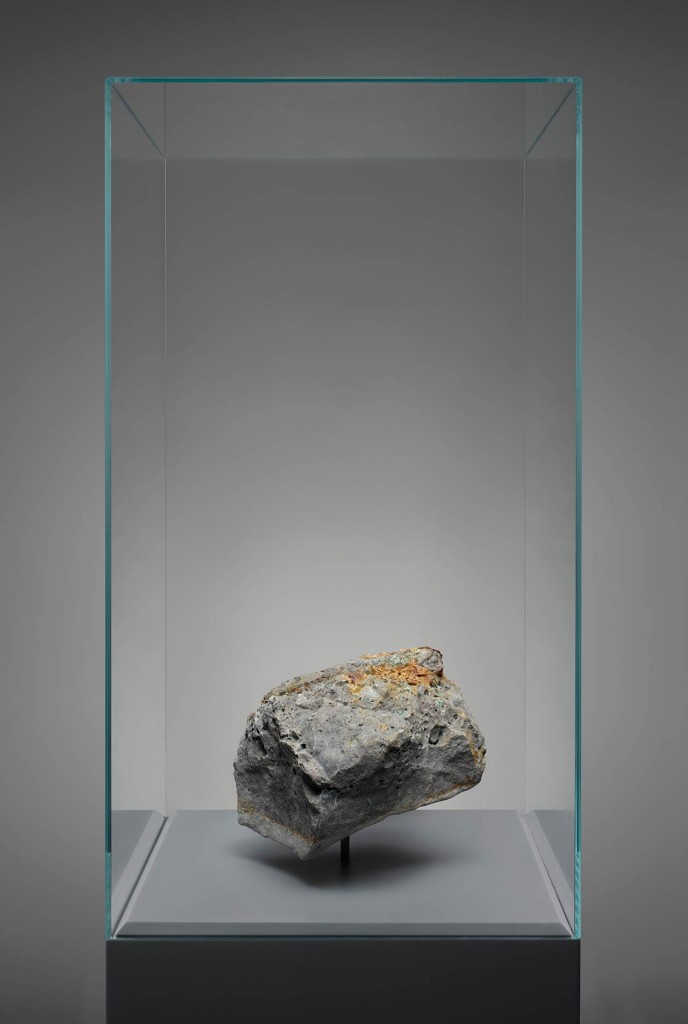

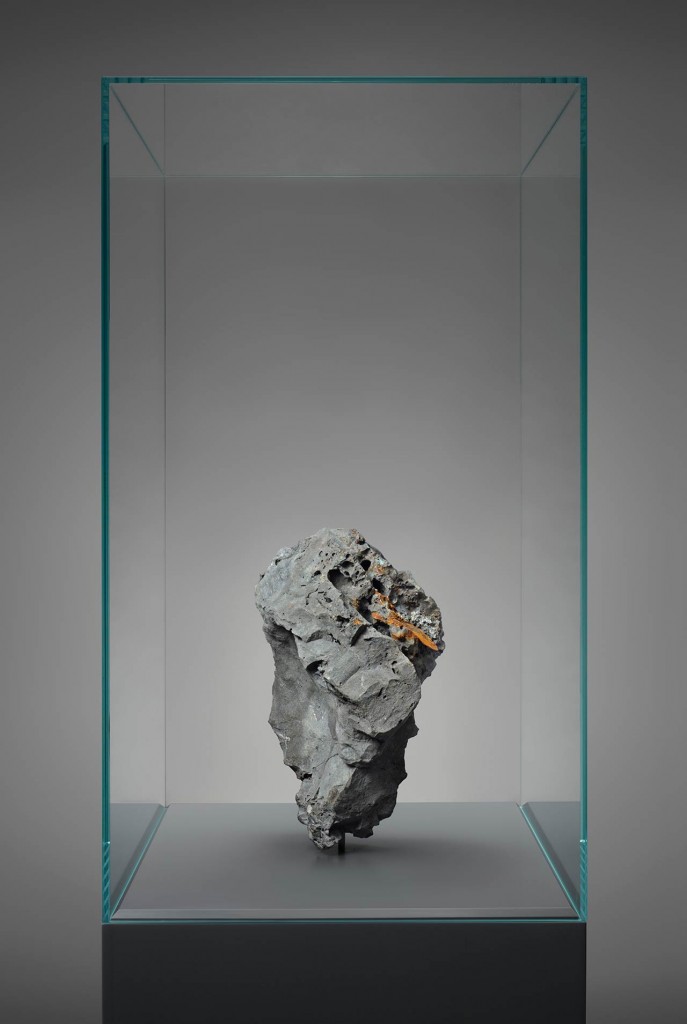

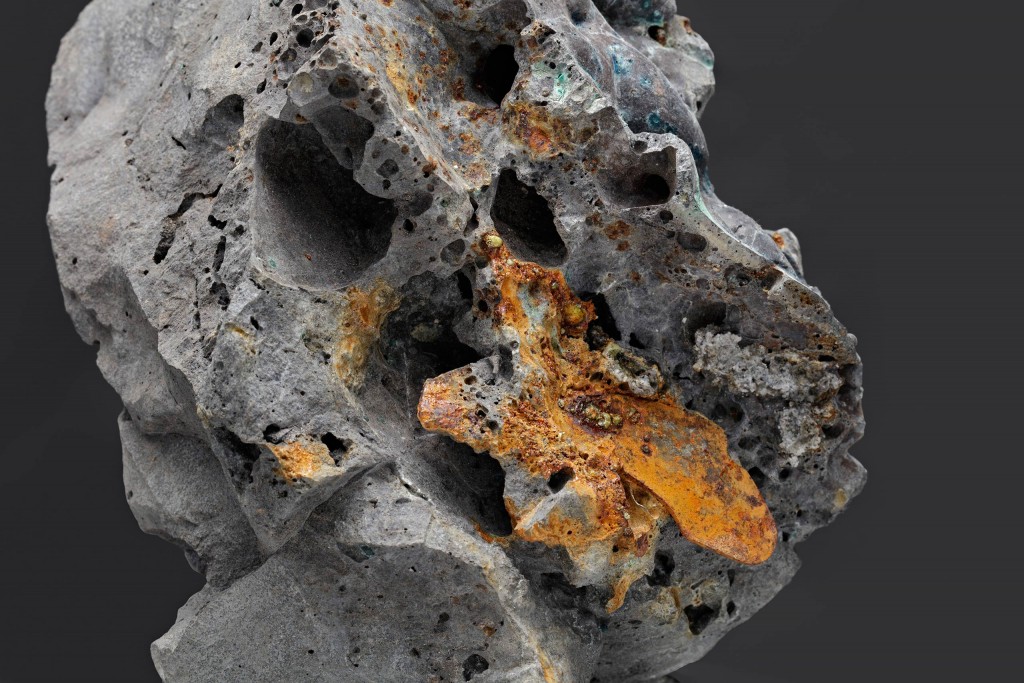

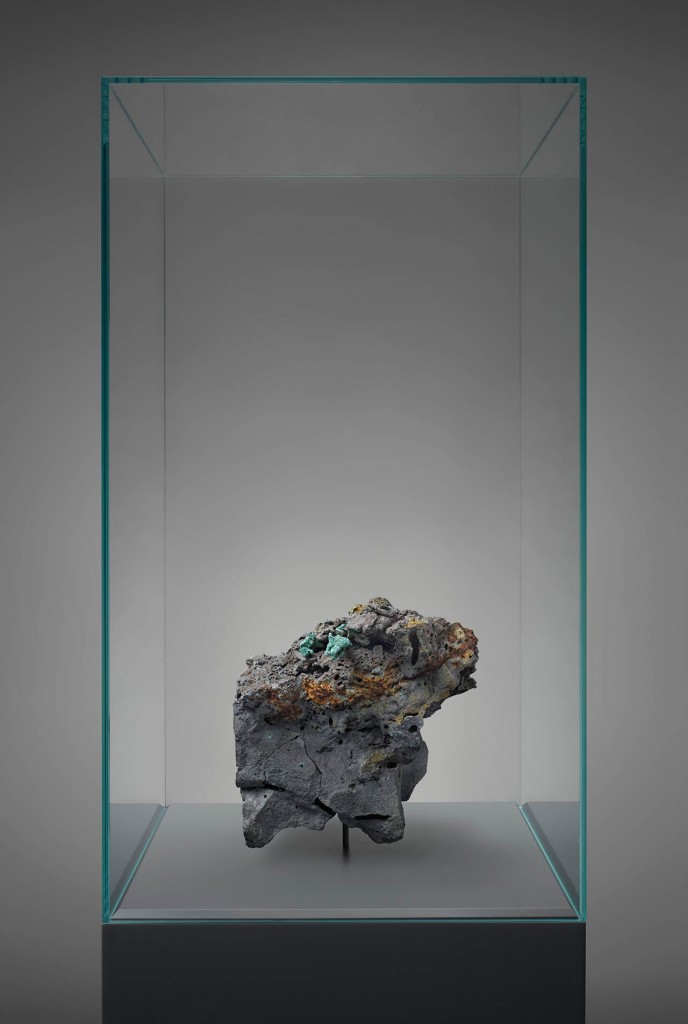

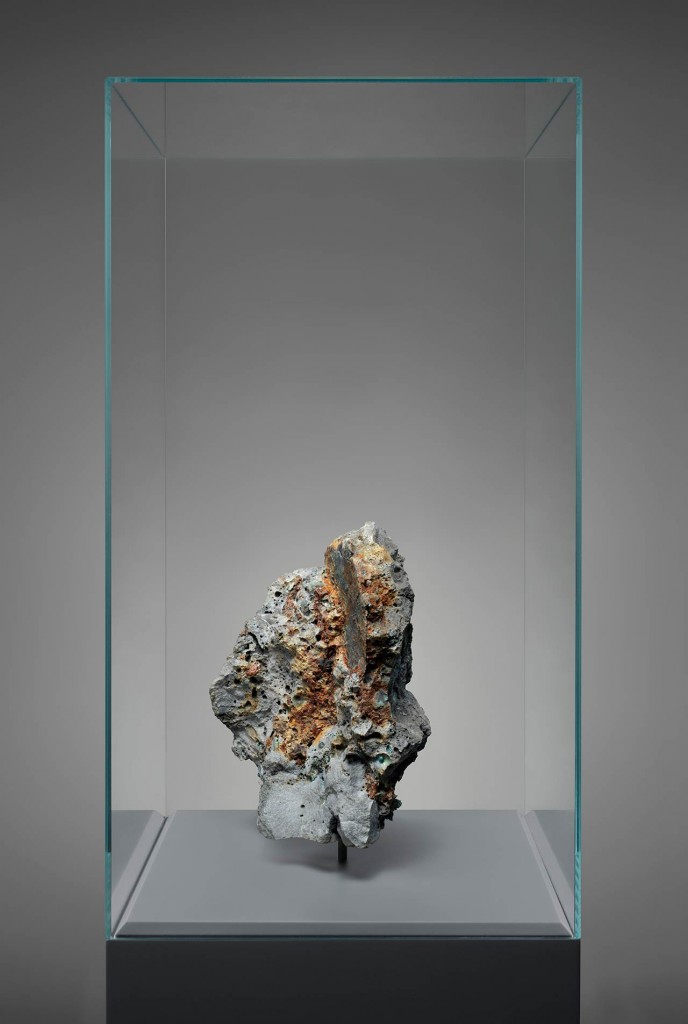

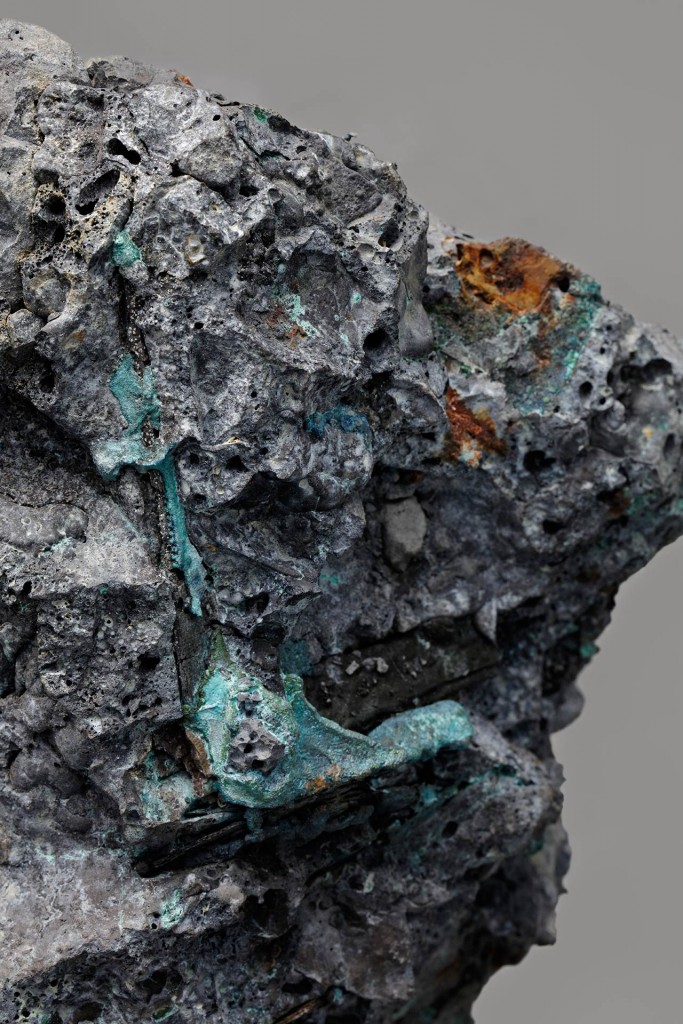

Negative sculptures unearthing resources for hardware on which source code finally melts down to software and the death drive of the hard drives finds for the ultimate penalty against itself in the Fossilicon Valley of Death, the inorganic exile of repetition. The paradise of the divine commodities is the inferno of others’ information. These alienated processes may be espied in the epistemic lumps Charrière puts on display. He took information technologies and magma to Thyssen-Krupp’s blast furnaces to smelt them into data rocks that stage an utterly new—holocene—object-oriented ontology and geology of technologies between the Congo Basin’s coltan mines and the NSA’s data mining: no longer “cogito ego sum” but now “cogito geo sum.”

The lumps of rock, this mountain-shelter of being, look, for the time being, like meteorites, crashed and impacted like Lucifer, deeply buried in the earth’s interior and hence rediscovered in the inferno they caused, dug up, brought to light. The truth is: this extraterrestrial reality has forever been here, always already created, never immaterial.

II. Capitalismans

“Capitalism, as project, emerges through a world-praxis that creates external natures as objects to be mapped, quantified, and regulated so that they may service capital’s insatiable demands for cheap nature. At the same time, as process, capitalism emerges and develops through the web of life; nature is at once internal and external. In this way of seeing, the oikeios is a general abstraction that gains historical traction only insofar as it provides the conditions for recasting the great drivers of world-historical change—foremost among them the perennial darlings of industrialization, imperialism, capitalism, modernity—as co-produced by humans and the rest of nature.”

Jason W. Moore, The Capitalocene. Part I: On the Nature & Origins of Our Ecological Crisis (2016)

In Dante’s underworld, the souls born into flesh must cross Acheron, the river of the suffering of the dead; the passage is paid with an obol to Charon the ferryman (in the Greek, κυβερνήτης, kubernétes, the first and last cyberneticist of them all). To die is to deal.

Cybernetic capitalism, too, requires rare and expensive metals so it can keep its channels of blissfully informed data flowing. Yet where Dante’s entire under- and overworld is hierarchical and concentric, structured by theo-teleology, the cartography of cybernetic capitalism maps a distributed network, though one that is not less but only the more subservient to the talisman of capital and power.

Not for nothing did Cerberus, the three-headed hound of Hades guarding the entrance to the underworld, lend his name, in 1978, to a distributed authentication service, a network protocol that guards the communication between client and server on the Internet.

Charrière’s artificial rocks materialize these very physical and metaphysical processes of market control and their Acherontian autonomy:

“A market needed no longer be run by the Invisible Hand, but now could create itself—its own logic, momentum, style, from inside. Putting the control inside was ratifying what de facto had happened—that you had dispensed with God. But you had taken on a greater, and more harmful, illusion. The illusion of control. That A could do B. But that was false. Completely. No one can do. Things only happen, A and B are unreal, are names for parts that ought to be inseparable …”

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

The history of these rocks is a rock-solid story—data strata—of an ultra-high-temperature, detached, autonomous production and accumulation process of technological objects—which, it has long been undeniable, have their own ontology—and their subjects. Subject to the perennial production of data, these subjects, commonly called “we,” exist solely on the outermost shell of the planet our technologies describe: the flat world of the user interfaces masks the media-ecological interior, the infrastructures that constitute these surfaces on which we believe we move and are in reality moved rather than movers. Julian Charrière’s lumps are also the rocks he throws through the panes of that glass house. Thrown up by the interior, they at once open up access to it.

Even before it was called “science fiction,” in the first heyday of industrialization, Jules Verne, in Voyage au centre de la Terre (1864), undertook a journey similar to Julian Charrière’s. His protagonists or agents subscribe to the idea that the earth is hollow (long a widely credited theory), and so they embark on a quest to find and explore the ecosystem inside the earth, formerly known as Dante’s Inferno. Having decoded an encrypted message from a scientist that identifies the opening in the earth’s surface—the crater of the Icelandic volcano Snæfellsjökull—they penetrate the earth’s various strata to reach the realm beyond history, the “first days of the world,” as the novel puts it. After subterranean ocean odysseys, expeditions through forests of (psychedelic) giant mushrooms, and encounters with dinosaurs, a volcanic eruption eventually spits them out through Mount Stromboli into a present between the ash clouds of industrialization and the ash plumes, simulated into reality by supercomputers, of Icelandic volcanoes such as Eyjafjallajökull.

Time travels, in other words, through the earth’s surface (Verne) or the user interface (Charrière) and “into the hollow,” through a Holocene that is forever new to us users of surfaces into the past eons disclosed to our experience only by measurements conducted under high-tech conditions, and into the reality, calculated from the future into the present, that lies before us in Julian Charrière’s rocks.

Seine Epochen sind keine hohlen Gleichnisse der Kultur- oder Kunstgeschichte. Seine Gegenwart ist das Holozän. Das Holozän ist der jüngste Zeitabschnitt der Erdgeschichte; es dauert bis heute an. In der Hierarchie der chronostratigraphischen Einheiten nimmt es den Rang einer Serie ein, wird aber nicht in Stufen unterteilt. Das Holozän begann vor etwa 11.700 Jahren mit der Erwärmung des Klimas am Ende des Pleistozäns. Holozän und Pleistozän gehören zum Quartär, dem jüngsten System des Känozoikums. In der englischen Literatur wird das Holozän mitunter auch als Present (dt. „Gegenwart“) bezeichnet.

Die Bezeichnung Holozän stammt aus dem Griechischen und bedeutet „das völlig Neue“ (von ὅλος, „völlig“, und καινός, „neu“). Der Begriff wurde um 1867/1869 durch den französischen Zoologen Paul Gervais geprägt. Bereits 1833 hatte Charles Lyell für diesen Zeitabschnitt der Erdgeschichte den Begriff Present geprägt. Auf dem 3. Geologischen Kongress in London 1885 setzte sich jedoch die Bezeichnung Holocene (eingedeutscht Holozän) gegenüber Present (Gegenwart) durch.

Wo spekulative Realisten wie Quentin Meillassoux mit feinst geschliffenen, hoch exklusiven und dabei zirkelschlüssigen Theoriezirkonen in die Marianengräben des Nichtmenschlichen hinein zu denken versuchen und dabei doch menschlich, allzu menschlich bleiben, berichtet Julian Charrière als Forscher – jedoch nicht im Sinne von „research“, also einer Wiedersuche, die herstellt, wonach sie fahndet – aus dem Inferno der Information.

I. The Divine Commodities

Vor mir ist kein geschaffen Ding gewesen,

Nur ewiges, und ich muss ewig dauern.

Lasst, die ihr eintretet, alle Hoffnung fahren!

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia (1307–1321): Inferno, dritter Gesang Inschrift auf dem Tor zur Hölle

I’m gonna put on a iron shirt, and chase the devil out of earth

I’m gonna send him to outa space, to find another race.

The Prodigy, Out of Space (1992)

Das Pragmagische donnert nicht im Kanon der Kanonen, sondern führt eine flüchtige, ständig den Aggregatszustand wechselnde Existenz im Magma der Vulkane. Wo Dante, nach der Weisung Vergils – „Du musst auf einem andern Wege gehen […] wenn du aus dieser Wildnis willst entfliehen“ – in die Psychogeografie der Göttlichen Komödie hinabsteigt, um Inferno und Purgatorio in Richtung Paradiso zu durchwandern, geht Julian Charrière in Into the Hollow den umgekehrten Weg, indem er von dem, was wir unsere göttlichen Commodities nennen könnten, ausgeht und die Halbwertszeit einer „Wastewilderness“ durchschreitet und in toxischer Tiefenzeit einschmilzt.

Dantes Topologie – der Krater oder Vortex, der ins unendlich Innere führt – ist jener eschatologische Bombenkrater, der entstand, als Luzifer vom Himmel fiel und auf der Erde einschlug. Dadurch faltete sich auf der anderen Seite des Erdballs der sogenannte Berg der Läuterung auf, auf dessen Gipfel das Paradies. Charrières Inferno der Information hingegen ist kein Ereignis, sondern ein Seinszustand, permanent, distribuiert, in Form jener Minen für seltene Erden und der darauf aufbauenden Infrastrukturen, die den Planeten durchmasern: Negative Skulpturen, die Ressourcen für Hardware zutage fördern, auf der schließlich Source Code zu Software schmilzt und sich der Todestrieb der Laufwerke – der death drive der hard drives – im anorganischen Exil der Repetition des Fossilicon Valley of Death selbst den Prozess macht. Das Paradies der göttlichen Commodities ist das Inferno der Information der anderen. Diese entfremdeten Prozesse finden sich in Charrières ausgestellten epistemischen Brocken. In den Hochöfen von Thyssen-Krupp schmolz er Informationstechnologien mit Magma zu Datengestein, das eine objektorientierte Ontologie und Geologie der Technologien zwischen den Coltanminen im Kongo und dem Data Mining der NSA völlig neu – holozän – in Szene setzt: Nicht mehr „cogito ego sum“, sondern „cogito geo sum“.

Die Gesteinsbrocken, dieses Gebirg des Seins, muten vorerst an wie Meteoriten, abgestürzt und eingeschlagen wie Luzifer, tief eingegraben ins Erdinnere und dort im Inferno, das sie verursacht haben, wiederentdeckt, geschürft, zu Tage gefördert. Dabei ist dieses Außerirdische stets hier gewesen, immer schon geschaffen, niemals immateriell.

II. Capitalismans

„Capitalism, as project, emerges through a world-prax is that creates external natures as objects to be mapped, quantified, and regulated so that they may service capital’s insatiable demands for cheap nature. At the same time, as process, capitalism emerges and develops through the web of life; nature is at once internal and external. In this way of seeing, the oikeios is a general abstraction that gains historical traction only insofar as it provides the conditions for recasting the great drivers of world-historical change – foremost among them the perennial darlings of industrialization, imperialism, capitalism, modernity – as co-produced by humans and the rest of nature.“

Jason W. Moore, The Capitalocene. Part I: On the Nature & Origins of Our Ecological Crisis (2016)

In Dantes Unterwelt müssen die eingeborenen Seelen den Acheron, den Fluss des Leidens der Toten, überqueren, wozu man Charon, dem Fährmann (griechisch κυβερνήτης, kybernétes, der erste und letzte Kybernetiker überhaupt) einen Obolus leisten muss. Sterben heißt Handeln.

Seltene und teure Metalle verlangt auch der kybernetische Kapitalismus, um seine Kanäle mit selig informierten Daten im Fluss halten zu können. Wo aber Dantes gesamte Unter- und Überwelt hierarchisch, konzentrisch und theo-teleologisch aufgebaut ist, kartografiert der kybernetische Kapitalismus ein distribuiertes Netzwerk, das dabei jedoch nicht weniger, sondern umso stärker dem Talisman des Kapitals und der Macht folgt.

Kerberos, der dreiköpfige Höllenhund, der den Eingang zur Unterwelt bewacht, heißt nicht umsonst seit 1978 auch ein verteilter Authentifizierungsdienst, ein Netzwerkprotokoll, das im Internet die Kommunikation zwischen Client und Server bewacht.

Charrières künstliche Gesteine materialisieren genau diese physischen und metaphysischen Kontrollvorgänge des Markts und ihre acherontische Autonomie:

“A market needed no longer be run by the Invisible Hand, but now could create itself – its own logic, momentum, style, from inside. Putting the control inside was ratifying what de facto had happened – that you had dispensed with God. But you had taken on a greater, and more harmful, illusion. The illusion of control. That A could do B. But that was false. Completely. No one can do. Things only happen, A and B are unreal, are names for parts that ought to be inseparable …“

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

Die Geschichte dieses Gesteins ist eine Gesteinsgeschichte – data strata – eines hocherhitzten, losgelösten, autonomen Produktions- und Akkumulationsprozesses von technologischen Objekten – denen eine Ontologie längst nicht mehr abzusprechen ist – und ihren der ewigen Datenproduktion unterworfenen Subjekten. Diese Subjekte, gemeinhin „wir“ genannt, existieren nur auf der äußersten Schale des Planeten, den unsere Technologien beschreiben: Die flache Welt der Benutzeroberflächen cachiert das medienökologische Innere, die Infrastrukturen, die diese Oberflächen, auf denen wir uns zu bewegen meinen und dabei doch eher bewegt werden, konstituieren. Julian Charrières Brocken sind auch die Steine, die er durch diese Glashausscheiben wirft. Sie öffnen Eingänge ins Innere im selben Maße, wie sie aus diesem hervorgetreten sind.

Noch bevor es „Science Fiction“ genannt wurde, zur ersten Hochzeit der Industrialisierung, unternahm Jules Verne in Voyage au centre de la Terre (1864) eine ähnliche Reise wie Julian Charrière. Auf Grundlage der Annahme, die Erde sei hohl (einer lange weit verbreiteten Theorie), machen sich seine Protagonisten oder Agenten auf den Weg, das Ökosystem im Inneren der Erde – vormals noch Dantes Inferno – zu finden und zu erkunden. Nachdem sie die verschlüsselte Nachricht eines Forschers, die die Öffnung in der Oberfläche – den Krater des isländischen Vulkans Snæfellsjökull – markiert, entschlüsselt haben, gelangen sie durch die Erdschichten schließlich ins Jenseits der Geschichte, in die „erste Erdperiode“, wie es im Roman heißt. Nach unterirdisch ozeanischen Irrfahrten, Expeditionen durch (psychedelische) Riesenpilzwälder und Begegnungen mit Dinosauriern spuckt ein Vulkanausbruch sie schließlich wieder aus dem Stromboli in eine Gegenwart zwischen den Aschewolken der Industrialisierung und den auf Supercomputern in die Realität simulierten Aschewolken isländischer Vulkane wie des Eyjafjallajökull.

Zeitreisen also, durch die Erd- (Verne) oder Benutzeroberfläche (Charrière) „into the hollow“, durch das für uns Oberflächenbenutzer ewig neue Holozän in die nur durch Messung unter hochtechnischen Bedingungen erfahrbaren vergangenen Äonen und die aus der Zukunft in die Gegenwart gerechnete Wirklichkeit, die in Julian Charrières Gesteinen vor uns liegt.