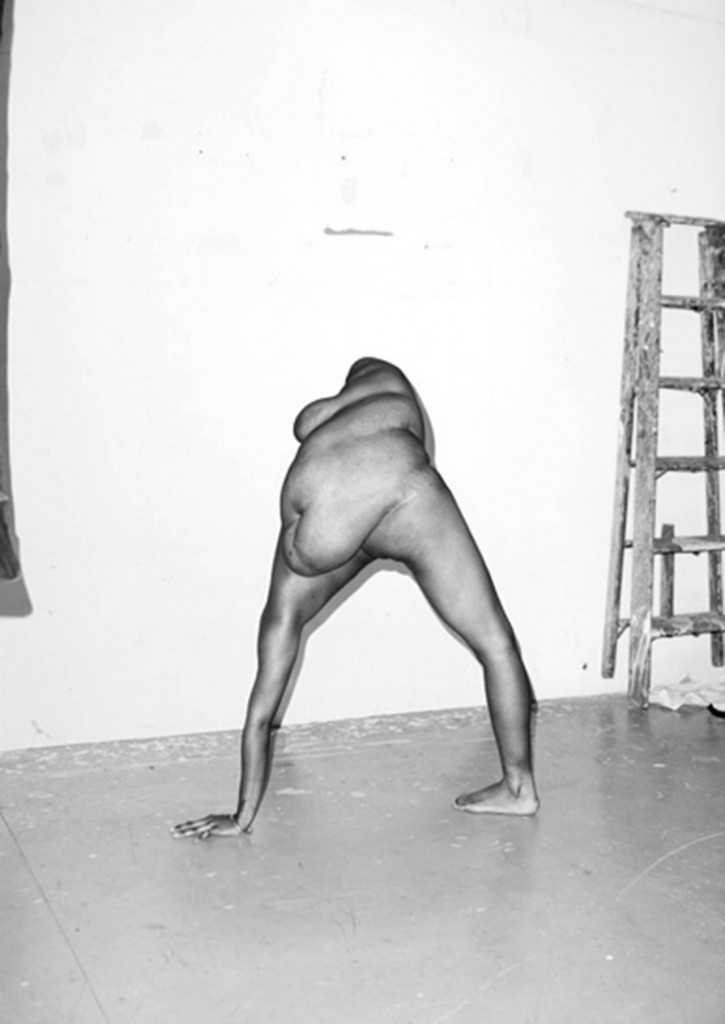

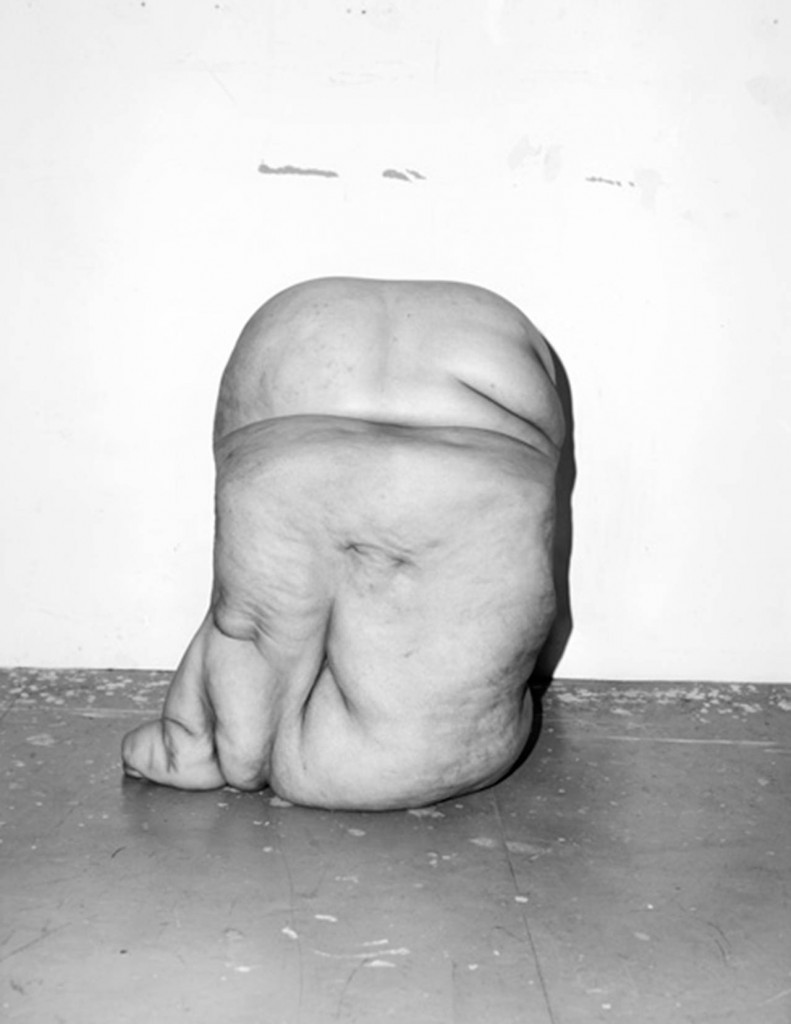

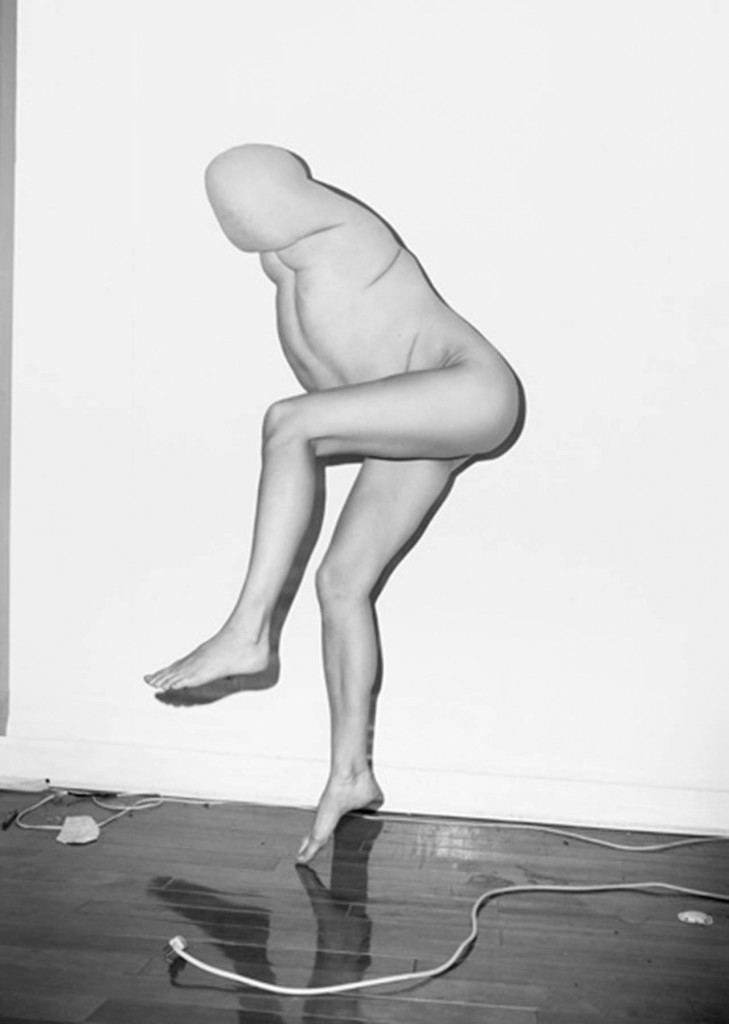

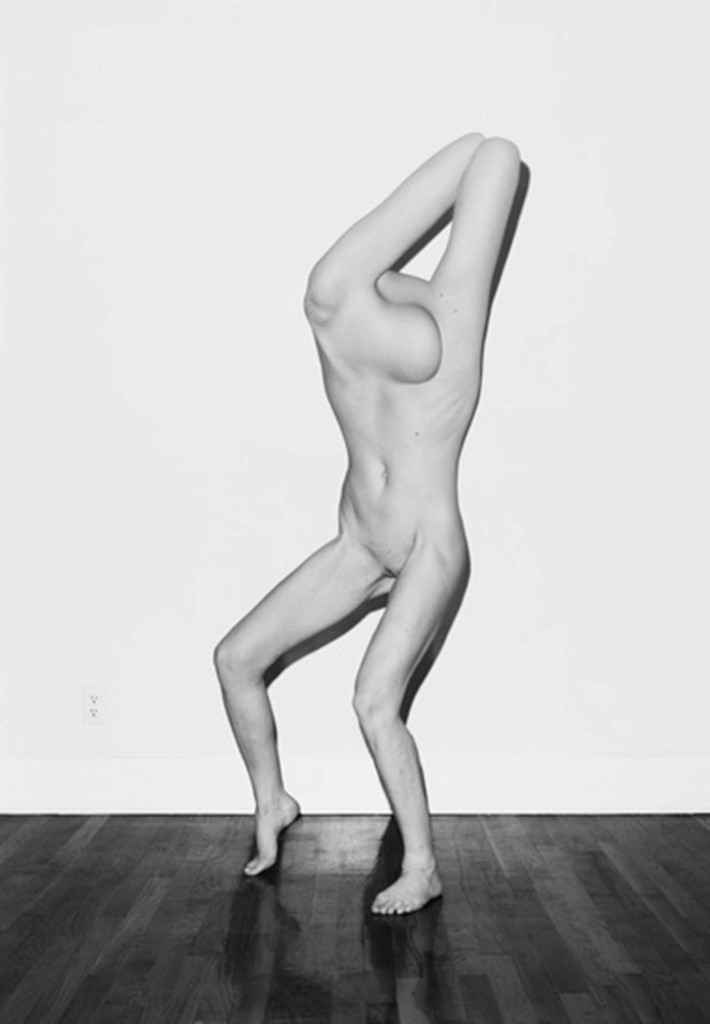

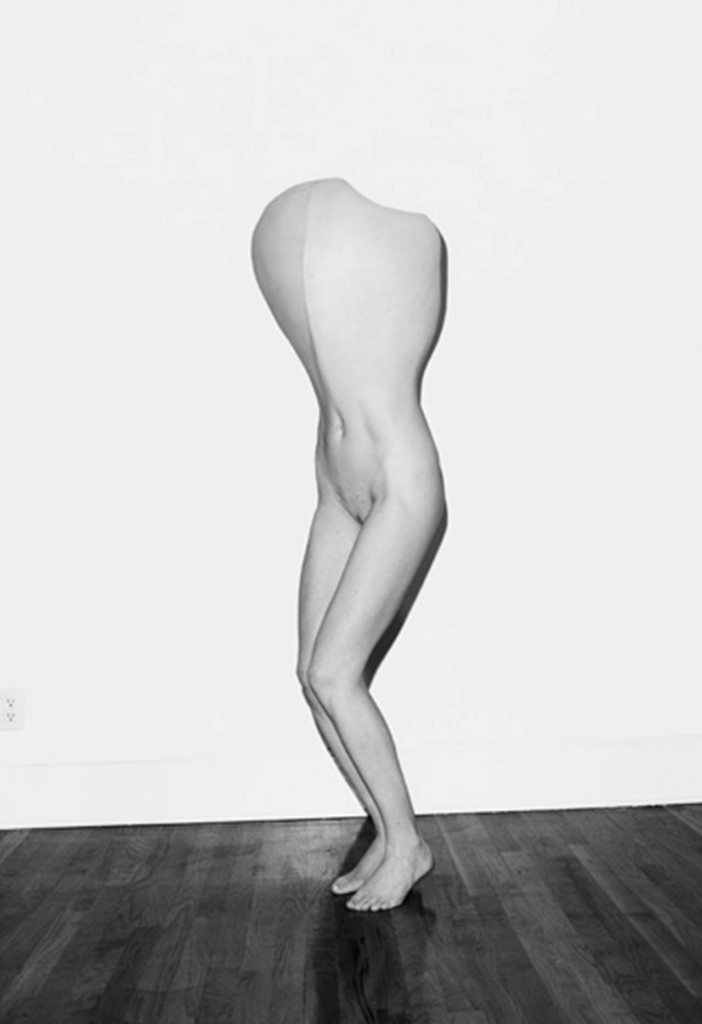

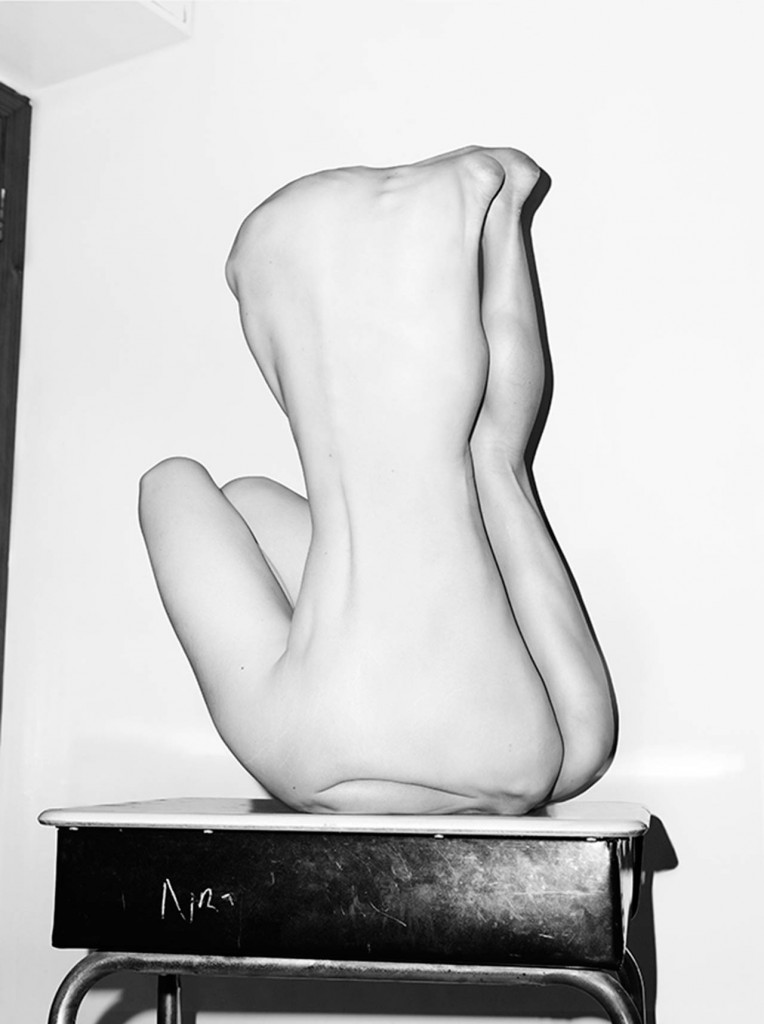

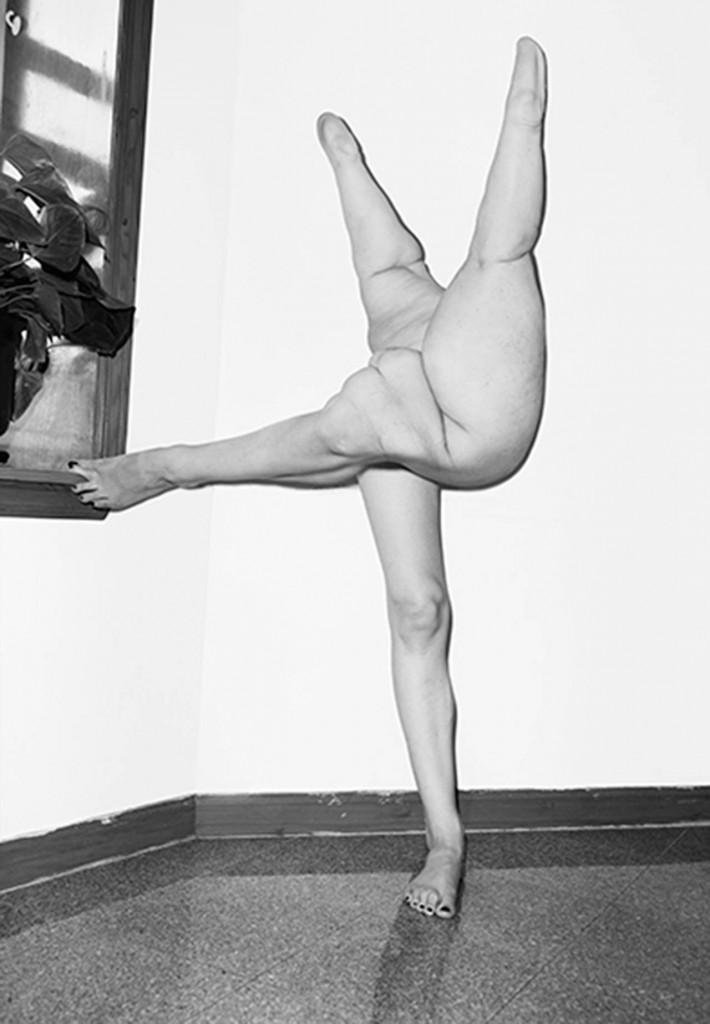

Carlsen creates his black-and-white photographs both in front of the camera and after the shot. In a first step, he captures images of models as weil as additional imitations of body parts made of modeling compound. In the subsequent time-consuming process of digital editing-the artist uses the program Photoshop-he assembles the individual parts that appear in the pictures so as to obscure the sutures. So the photographic act properly speaking is the work of a brief moment in relation to the creative process on the computer: “A one-hour photo session becomes material for years of work in my computer. “1 The provocation of the subject of his pictures clashes with the mastery of the editing. The body that emerges irritates the human eye with its striking homogeneity. The selective and carefully considered composition of the bodies and pictorial spaces, the meticulous lighting, which renders the pictures almost palpably vivid, and the nuanced grayscale attest to the artist’s love of detail and extraordinary artistic skill. Umfangreiche Bildbearbeitung ist eine in der heutigen Fotografie, insbesondere der Mode- und Werbefotografie, etablierte Praxis. Schon seit ihrer Erfindung ist die Fotografie ein Medium, das seine Überzeugungskraft nicht nur aus der Nähe zur Realität, sondern auch aus der Kraft der Imagination bezieht: Mit Inszenierung und Retusche lassen sich imaginäre und glaubwürdige Bilderwelten erschaffen.

In contemporary photography, and in fashion and advertising photography in particular, comprehensive image editing is standard practice. Ever since it was first invented, photography has always been a medium whose power to convince flows not just from its proximity to reality, but also from the energy of the imagination: staging and retouching allow for the creation of imaginary and yet persuasive visual worlds. The photographic process has long allowed for a broad range of interventions. Only in rare instances, however, are they recognizable at first glance.

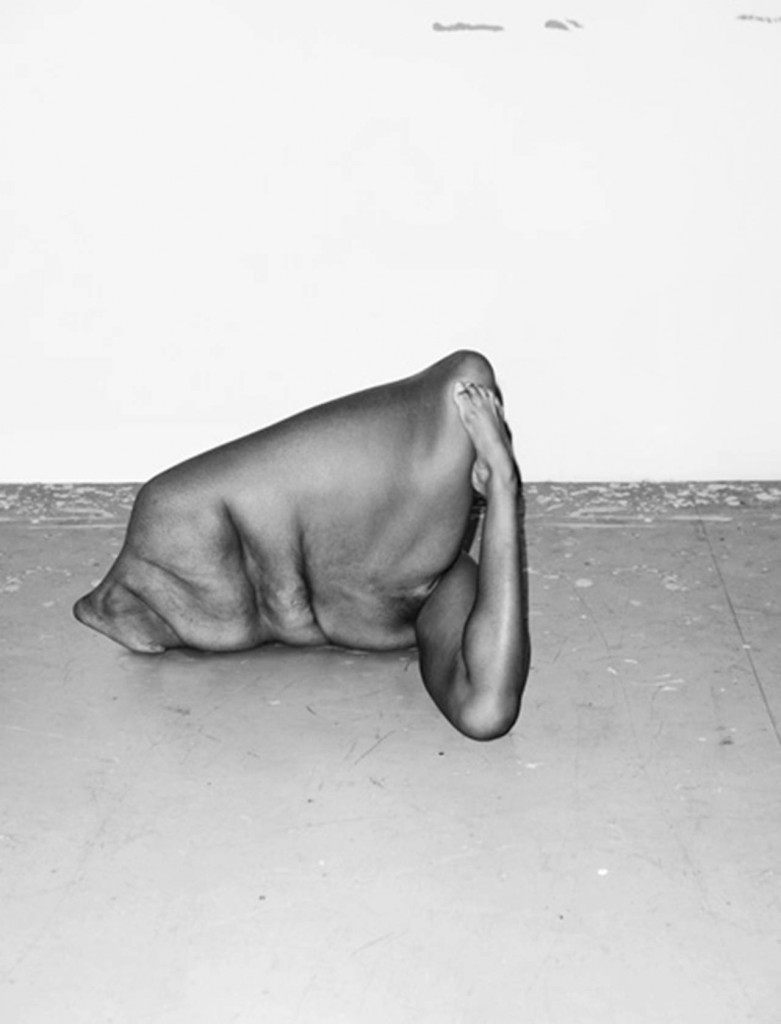

lt is widely known today that photographs do not show the truth. So if the contemporary beholder’s eyes are not liable to be taken in by illusions, why are Carlsen’s pictures so provocative? ls it the aggressive negation of the ideal of beauty circulated by the media, which calls for undamaged, slender, symmetrical bodies? Not unlike the painted portraits of Lucian Freud or Jenny Saville, Carlsen’s pictures do not shy away from showing wrinkles, rings of fat, and dimpled skin. On the contrary: “Hester” presents such features not as flaws but as different aesthetic physicalities. The amputation and arbitrary montage of limbs, moreover, runs counter to the idea that the intactness and integrity of the human body is the measure of its normalness and functionality. Carlsen’s photographs once again remind us that, our ostensible tolerance and enlightened views notwithstanding, there are taboos against the depiction of certain things in art.

The profound sense of discomfort provoked by the sight of these objects has yet another source: even if the bodies are recognizably imaginary constructs, their existence is nonetheless within the realm of the possible or conceivable. With “Hester,” the artist revives a debate that first arose in the 1990s, when digital photography was-rather hastily-interpreted as a visual harbinger of tissue engineering and cloning. When artists like lnez van Lamsweerde or Aziz + Cucher first started exploiting the creative potential of digital image editing, critics coined the skeptical concept of “photogenics.”2 The resemblance between the work of the human geneticist in the laboratory and the artist’s creation of artificial beings on the computer seemed just too close. That is because a credibility bonus still clings to everything photographic: as Walter Dadek put it, we are “compelled to assume that the object depicted actually exists, the reservations of our critical mind notwithstanding.”3

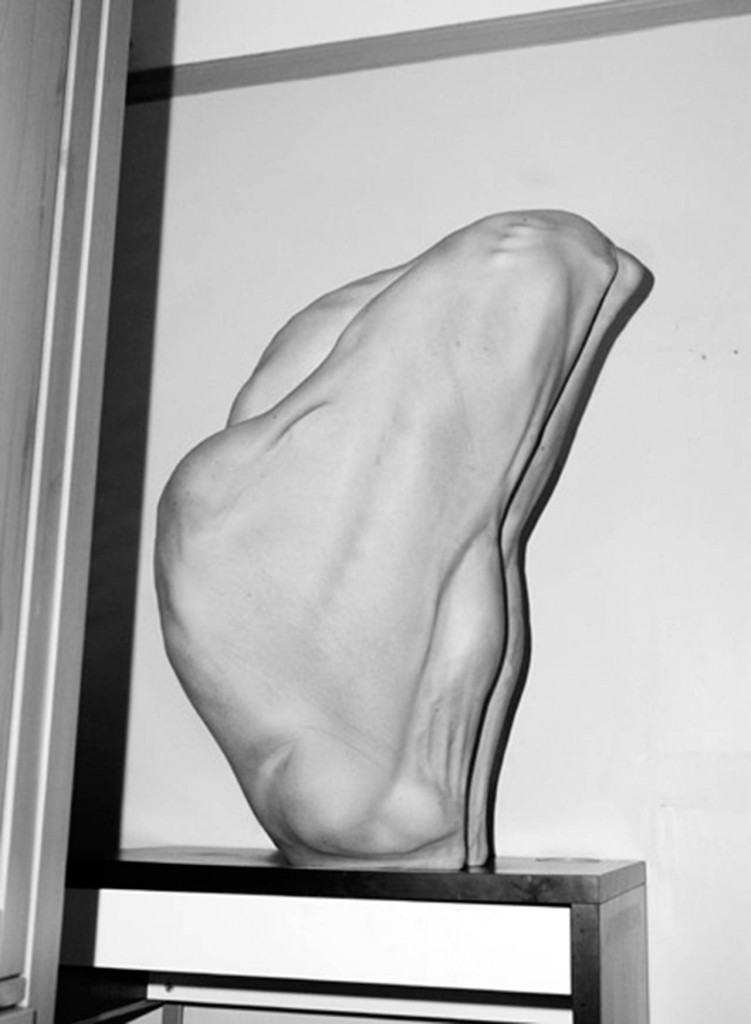

The expansion of the concept of the photographic medium is probably also one reason why Carlsen himself regards his pictures as artistic creations rather than photographs. “Making Hester was more of a sculptural challenge and had very little to do with being a photographer.”4 Looking at “Hester,” we are in fact unsure what it is we see: Photographs? Sculpture? Photographs of sculpture? There are indeed points of comparison in the history of painting and sculpture that may help us understand Carlsen’s art. Following the example of abstract art, and more particularly of early twentieth-century synthetic cubism, Carlsen, working on the computer, processes several views at once, deconstructing their forms and reassembling them; the goal is not just to depict human bodies, but to render a vivid experience of them. Still, photography has a distinctive penetrating power that painting, sculpture, or drawing lack. Simply imagine, for example, Carlsen’s works not as photographs of objects but as three-dimensional sculptures made of classical materials such as marble, bronze, or copper. That would presumably make them comparable to, say, Henry Moore’s sculptures, which are regarded as pure and hyperaesthetic forms.

Georges Braque is supposed to have said that “il ne taut pas imiter ce que l’on veut creer [ … ] Les sens deforment, /’esprit forme.” -One must not imitate what one would create. The senses deform, the mind forms. In “Hester,” Carlsen, a former forensic photographer who used to document crime scenes and victims for New York’s police, works against the reduction of photography to a medium of depiction. He represents a generation of artists who aggressively harness the potentials of digital image editing for their creative processes. Complex images result that invite us to look afresh at the paradoxes of photography, the contradictions of its relation to reality, and its subliminal veracity.

1 Asger Carlsen in einem Interview mit Austin McManus in: Juxtapos, January 2013, pp. 78-87.

2 Geoffrey Batchen, Photogenics/Fotogenik, in: Camera Austria International 62-3 (1998): pp. 5-16.

3 Walter Dadek, Das Filmmedium. Basel, 1968, p. 95.

4 Asger Carlsen in: Juxtapos, p. 81.

Carlsen kreiert seine Schwarzweißfotografien sowohl vor der Kamera als auch nach der Aufnahme. In einem ersten Schritt werden Fotomodelle sowie zusätzliche aus Modelliermasse geformte Körperimitationen abgelichtet. Bei der anschließenden aufwendigen digitalen Bearbeitung der Fotografien mit dem Bildbearbeitungsprogramm Photoshop, werden die fotografierten Einzelteile so zusammengefügt, dass die Schnittstellen unkenntlich gemacht werden. Das eigentliche Fotografieren ist im Verhältnis zur Kreation am Computer also ein kurzer Moment: ,,A one-hour photo session becomes material for years of work in my computer. “1 Der Provokation durch das Bildsujet, steht die meisterliche Bearbeitung der Bilder gegenüber. So entsteht ein für das menschliche Auge irritierend homogener Körper. Die ausgewählte, durchdachte Komposition der Körper und Bildräume, die Lichtdramaturgie, welche die Dreidimensionalität unterstreicht, sowie die Bandbreite an Graustufen zeugen von Detailliebe sowie künstlerischer Virtuosität.

Umfangreiche Bildbearbeitung ist eine in der heutigen Fotografie, insbesondere der Mode- und Werbefotografie, etablierte Praxis. Schon seit ihrer Erfindung ist die Fotografie ein Medium, das seine Überzeugungskraft nicht nur aus der Nähe zur Realität, sondern auch aus der Kraft der Imagination bezieht: Mit Inszenierung und Retusche lassen sich imaginäre und glaubwürdige Bilderwelten erschaffen.

Die möglichen Eingriffe während des fotografischen Prozesses waren und sind höchst vielfältig. Auf den ersten Blick wahrnehmbar sind sie jedoch in den seltensten Fällen.

Dass Fotografien nicht die Wahrheit zeigen, ist heute allgemein bekannt. Wieso also provozieren die Bilder Carlsens dennoch den eigentlich so abgeklärten Blick des zeitgenössischen Betrachters? Ist es die offensive Negation des medial zirkulierenden Schönheitsideals, welches auf Unversehrtheit, Schlankheit und Symmetrie basiert? Ähnlich den gemalten Portraits Lucian Freuds oder Jenny Savilles scheuen Carlsens Bilder die Darstellung von Falten, Fettringen und Orangenhaut nicht. Im Gegenteil: Bei „Hester” erscheinen sie nicht als Makel, sondern als unterschiedliche ästhetische Materialitäten. überdies läuft die Amputation und willkürliche Montage von Gliedmaßen dem Gedanken der Unversehrtheit und Integrität des menschlichen Körpers als Maß seiner Normalität und Funktionalität zuwider. Die Fotografien Carlsens erinnern einmal mehr daran, dass ungeachtet unserer vermeintlichen Toleranz und Aufklärung, Tabus des Darstellbaren in der Kunst existieren.

Die Verstörung, welche die Betrachtung dieser Objekte hervorruft, rührt auch noch woanders her: Selbst wenn sich die Körper als imaginäre Konstrukte zu erkennen geben, liegt ihre Existenz dennoch im Bereich des Möglichen oder Vorstellbaren. Mit „Hester” knüpft der Künstler an eine Diskussion an, die bereits in den Neunzigern ihren Anfang nahm. Damals wurde die digitale Fotografie voreilig als visueller Vorbote des tissue engineerings und c/onings interpretiert. Als Künstler wie lnez van Lamsweerde oder Aziz + Cucher die gestalterischen Möglichkeiten der digitalen Bildbearbeitung erstmals ausreizten, kam der skeptische Begriff „Photogenics”2 auf. Zu sehr schien die Arbeit der Humangenetiker im Labor der künstlerischen Arbeit am Computer bei der Hervorbringung artifizieller Gebilde zu ähneln. Denn nach wie vor haftet allem Fotografischen ein Glaubwürdigkeitsbonus an, da wir, wie es Walter Dadek formulierte, ,,trotz aller Vorbehalte unseres kritischen Verstandes gezwungen sind, die Existenz des abgebildeten Objekts als tatsächlich gegeben anzunehmen.”3

Mit der Erweiterung des fotografischen Medienbegriffs dürfte auch der Umstand zusammenhängen, dass Carlsen selbst seine Bilder weniger als Fotografien denn als künstlerische Gebilde begreift. ,,Making Hester was more of a sculptural challenge and had very little to do with being a photographer. “4 Tatsächlich weiß der Betrachter nicht, was er bei „Hester” sieht: Fotografie? Skulptur? Fotografierte Skulptur? Um Carlsens Kunst zu begreifen, bieten sich in der Tat Vergleiche mit der Geschichte der Malerei und Skulptur an. Im Sinne der abstrakten Kunst, insbesondere des synthetischen Kubismus zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts, verarbeitet Carlsen am Computer mehrere Ansichten gleichzeitig, indem er ihre Formen dekonstruiert und neu zusammenfügt mit dem Ziel, menschliche Körper nicht nur abzubilden, sondern regelrecht erfahrbar zu machen. Dennoch ist der Fotografie eine andere Durchschlagskraft im Gegensatz zu Malerei, Skulptur oder Zeichnung eigen. Die simple Vorstellung etwa genügt, Carlsens Werke wären nicht Fotografien von Objekten, sondern dreidimensionale Skulpturen aus klassischen Materialien wie Marmor, Bronze oder Kupfer. Dann wären sie wohl durchaus mit den Skulpturen Henry Moores vergleichbar, welche als reine, hyperästhetische Formen betrachtet werden.

Georges Braque wird das Zitat zugeschrieben: ,,// ne taut pas imiter ce que l’on veut creer. [ … ] Les sens deforment, /’esprit forme.” – Man sollte das, was man schaffen möchte, nicht imitieren. Die Sinne deformieren, der Geist formt. Als ehemaliger Tatortfotograf, der einst im Auftrag der New Yorker Polizei Orte und Opfer von Verbrechen dokumentierte, arbeitet Carlsen mit „Hester” gegen die Begrenztheit der Fotografie als Medium der Abbildung. Er gehört zu einer Generation von Künstlern, welche die Möglichkeiten der digitalen Bildbearbeitung offensiv für ihre Schaffensprozesse nutzen. So entstehen komplexe Bilder, die die Paradoxien der Fotografie, ihre Widersprüchlichkeiten im Verhältnis zur Realität und ihre untergründige Wahrhaftigkeit neu zur Disposition stellen.

1 Asger Carlsen in einem Interview mit Austin McManus in: Juxtapos, January 2013, pp. 78-87.

2 Geoffrey Batchen, Photogenics/Fotogenik, in: Camera Austria International 62-3 (1998): pp. 5-16.

3 Walter Dadek, Das Filmmedium. Basel, 1968, p. 95.

4 Asger Carlsen in: Juxtapos, p. 81.