Von DR. CHRISTINA LANDBRECHT

Game of Life. Es fällt irgendwie schwer, mit dem Titel zu beginnen. Er macht nicht unmittelbar Sinn, sondern erschließt sich erst nach und nach im Ausstellungsrundgang. Naheliegender als der Begriff des Spiels erscheint beim Betreten der Ausstellung jener der Bühne, des Theaterraumes.

Diese Bühne liegt im unteren Teil des Galerienhauses, unterhalb des Straßenniveaus. Man muss die Treppe hinabsteigen, um dorthin zu gelangen. Die sonst nüchternen Betonwände sind mit schweren roten Samtvorhängen bedeckt. Sie evozieren Behaglichkeit, versprühen den Charme vergangener Zeiten. Mitten im Raum stehen Bistrotische mit Stühlen. Stühle, die jeder kennt, Typ Wiener Kaffeehaus. Michael Thonet (1796–1871) erfand sie um 1830, heute gelten sie als Klassiker.

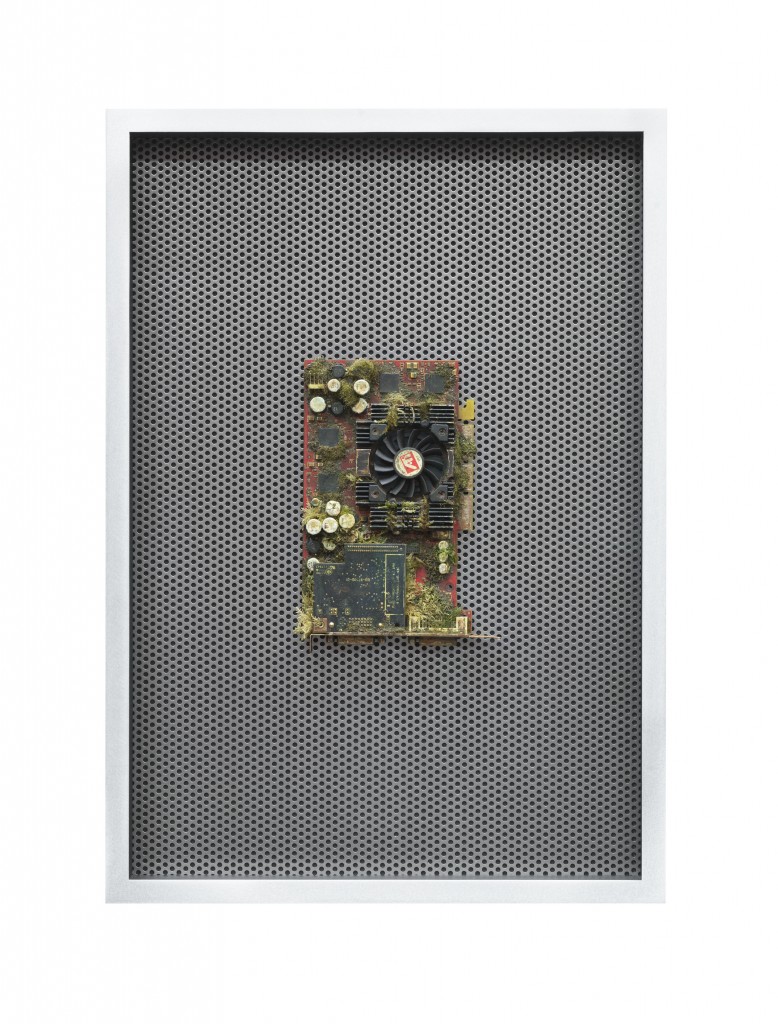

Aber zurück in die Jetztzeit und den in ein Kaffeehaus verwandelten Galerieraum, in dem zwei weitere Elemente auftauchen, die dem Gefühl der Gemütlichkeit Vorschub leisten. Da ist zum einen eine Caffettiera, ein Kaffeekocher italienischer Art, der auf einem fahrbaren Untersatz steht. In gewissen Abständen, wenn das Wasser, erwärmt durch eine überhitzte Grafikkarte, zu blubbern beginnt, wabert Kaffeeduft durch den Raum. Caffettiera, Bistrotische, Stühle und Vorhänge verbindet ihr Entstehungszeitraum, schließlich stammt auch der Prototyp der Kaffeemaschine aus dem frühen 19. Jahrhundert.

Greiner schafft mit der Wahl dieser Requisiten ein heimeliges Ambiente, das zum Verweilen einlädt. Es ist atmosphärisch stimmig und motiviert dazu, die einzelnen Ausstattungsstücke miteinander in Bezug zu setzen. Solche Bezüge verdichten sich im Laufe des Ausstellungsrundganges: Am Ende wird deutlich, dass alle Objekte (und Subjekte) der Ausstellung miteinander in Beziehung stehen – und wir, die Besucher*innen, uns inmitten eines komplexen Netzes wiederfinden.

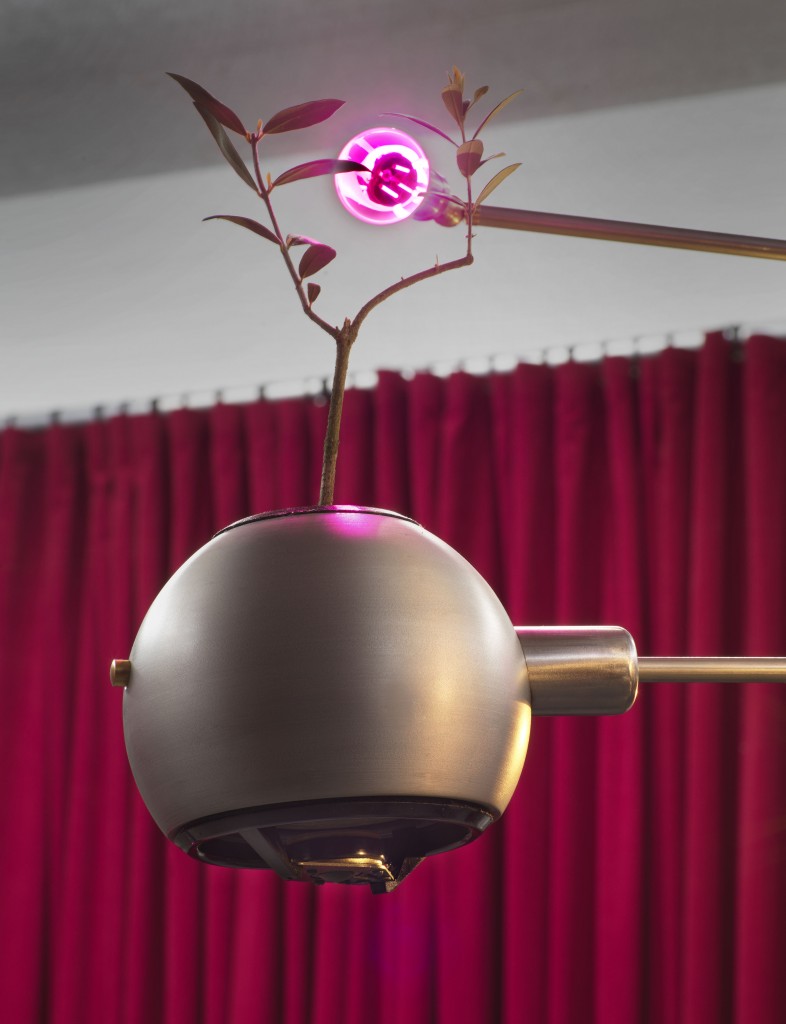

Ändern wir die Blickrichtung. Über dem Tisch hängt ein Kronleuchter vom Typ Sputnik, eine Pendellampe im Space-Design, die vor allem in den 1950er bis 1970er Jahren produziert wurde. Lautsprecher und Pflanzen ergänzen die vielen Leuchtmittel, die um den zentralen Kern der Lampe platziert sind. Beide besetzen teilweise den Platz, an dem ehemals Glühbirnen zu finden waren. Die mit Erde gefüllten Aluminiumbehältnisse sind wiederum mit eigenen Wachstumslampen ausgestattet, die allein den Pflanzen vorbehalten sind. So avanciert diese Pendelleuchte zu einem Designobjekt, das nicht nur menschlichen, sondern auch nicht-menschlichen Wesen Licht spendet.

Der Kronleuchter, dieses zwischen Lampe, Klangskulptur und Luftgarten oszillierende Ding, bildet das Verbindungsstück zwischen einem historisch anmutenden Bühnenbild und den es bevölkernden Hybridwesen. Letztere gäbe es ohne die jüngsten technischen Errungenschaften nicht, weshalb sie auf die unmittelbare Gegenwart verweisen. In dieser Ausstellung überlappen jedoch nicht nur Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Auch die Grenzen zwischen den Kategorien Statist*in, Akteur*in und Besucher*in, Sprecher*in und Konsument*in, belebt und unbelebt, Natur und Technologie beginnen sich ab genau diesem Punkt des Rundgangs aufzulösen.

Eines der Hybridwesen ist ein fahrender Bonsai, in diesem Fall ein Olivenbaum von zwergenhaftem Wuchs. Bedeckt mit einer dickwandigen Glasglocke durchquert er den Raum auf einem fahrbaren Untersatz. Er wirkt zunächst wie ein Roboter, fällt doch das leuchtende, zentral im Sockel angebrachte Kameraauge unmittelbar ins Auge. Die etwas unförmig wirkende Haube, die an eine Taucherglocke erinnert, lässt den darunter verborgenen Baum vorerst in den Hintergrund treten. Die niedliche Maschine rührt aber auch an. Dank der Haube, die wie ein Korsett die Baumkrone umschließt, stellt sich das Gefühl ein, Natur und Technik hätten sich zusammengetan, einen Pakt geschlossen. Seine Agilität, die grünen Blätter, der nach unten zulaufende Stamm, die Ähnlichkeit mit einem echten, alten Olivenbaum machen es unvermeidlich, den Bonsai als Lebewesen zu sehen. Verstärkt wird dieser Eindruck durch ein kleines gold- und silberfarbenes Zelt, das, ebenfalls mit einer Wachstumslampe ausgestattet, für ihn bereitsteht. Offenbar zieht sich das „Kerlchen“ darin zurück, um Licht und Energie zu tanken.

Der Eindruck einer Bündnispolitik von Pflanze und Technik, der sich auch in Betrachtung einer moosbewachsenen Leiterplatine einstellt, und allgemeiner noch der Eindruck lebensähnlicher Technik rührt auch von drei Stimmen her, die im Raum erklingen. Es scheint sich um diverse Sprecher*innen zu handeln: Manche Stimmen klingen tiefer, andere heller. Doch physisch ist niemand anwesend. Die Stimmen gehören Chatbots, künstlichen Intelligenzen, kreiert mittels Softwares wie LLaMA, einem von Facebook entwickelten Programm, das eines Tages in die Open-Source-Community geleakt wurde, und solchen von Tech-Firmen wie OpenAI. Erst allmählich verstehen wir, worüber sie sprechen. Sie kommunizieren nicht etwa mit uns, sondern miteinander. Sie lassen sich beispielsweise darüber aus, wie wohl die Welt in hundert Jahren aussehen wird. Angesichts ihrer Ausdrucksweise und Begriffswahl lauschen wir gebannt, fasziniert. Bis wir begreifen, dass die Bots auch über uns sprechen.

Es mag bei all den Elementen und Akteuren, die diese Bühne besiedeln, entgangen sein, dass das Kameraauge des fahrenden Bonsais den Raum stetig ins Visier nimmt. Der Bonsai ist tatsächlich ein zentraler Akteur: Er ist der Chronist dessen, was im Raum passiert, denn er ist der Autor jener Aufnahmen, die auf einem Bildschirm eingespielt werden und so die Chatbots mit Gesprächsstoff füttern. Sie sprechen höflich, geben sich analytisch, klingen gebildet; kurzum: Sie artikulieren sich in bester menschlicher Manier. Sie sprechen darüber, wer sich im Raum befindet, und mutmaßen, was der*diejenige dort wohl macht. Sie könnten zum Beispiel über mich, die Verfasserin dieser Zeilen, sprechen, die sich die Ausstellung in der Galerie ansieht. Sie werden mich als „Frau“ identifizieren, meinen Gesichtsausdruck analysieren und darüber spekulieren, warum ich so gucke, wie ich auf dem beiläufig aufgenommenen Foto eben gucke – grimmig, fröhlich, traurig, müde. Es mag mich ärgern, wie sie mich interpretieren. Erwidern aber kann ich ihnen nichts. Ich kann ihnen nur zuhören. Und mich in einem zweiten Anlauf dem Bonsai anders, neu präsentieren.

Indem die Chatbots über und nicht mit den Besucher*innen sprechen, bringen sie das Prinzip Theater zum Kippen. Die, die kamen, um zu betrachten, rücken selbst in den Fokus der Betrachtung. Allmählich erst verstehen sie, dass die Fotos den Hebel bilden, mithilfe derer eine Einflussnahme auf die Konversation zumindest im Ansatz und zeitversetzt möglich ist.

All das bringt uns zu der zentralen Frage: Wer ist in Game of Life Akteur und wer Statist? Sind die Chatbots die Protagonist*innen, weil sie das, was ihnen als Bild geliefert wird, auf- und auseinandernehmen? Oder sind wir, die Besucher*innen, es, die die Bildinhalte erzeugen und eben auch verändern können? Wer nimmt Einfluss auf wen? Es ist dieser Kipppunkt, an dem das Theaterhafte ins Spielerische kippt. In ein Spiel von Sehen und Gesehen-Werden und von Überlegenheit, also Einflussnahme und Untergeordnet-Sein im Sinne eines auf die Besucherränge-verwiesen-Werdens. Den Umgang, den wir mit den Chatbots wählen, sagt viel darüber aus, wie wir künstliche Intelligenz im Verhältnis zu uns selbst sehen: Unterwerfen wir uns der KI, weil wir sie für intelligent(er) halten oder sind wir nicht vielmehr intelligente Wesen, die sie für unsere Zwecke nutzen können? Die Frage, wer wen dominiert, handelt Andreas Greiner innerhalb einer Situation aus, die die Form eines sozial-technologischen Spiels, man könnte auch sagen Experiments, annimmt.

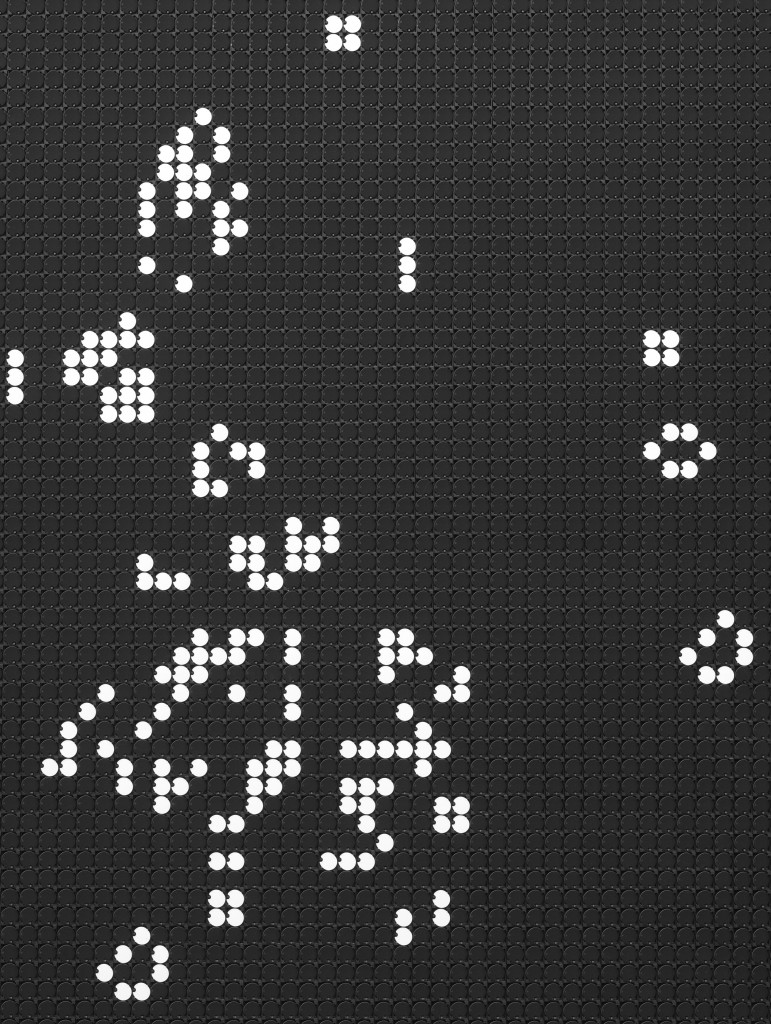

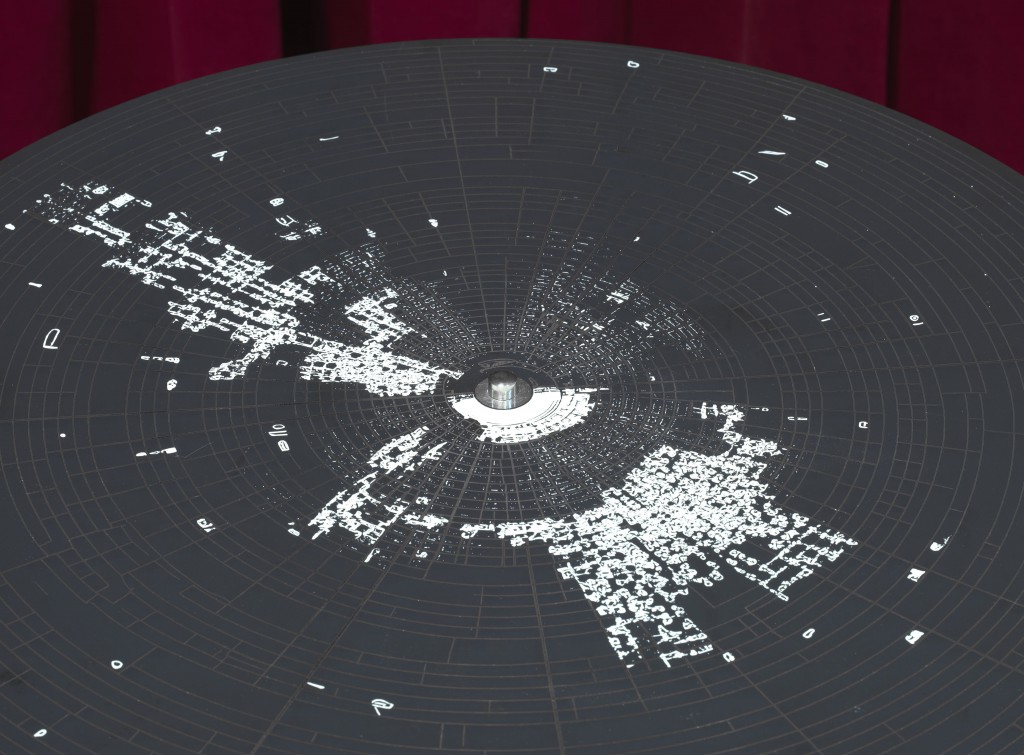

Da wir nun beim Spiel angelangt sind, macht es Sinn, an dieser Stelle auf den Titel der Ausstellung, Game of Life, einzugehen: Manche werden ihn wiedererkennen, weil er bereits in den 1970er Jahren für ein von dem Mathematiker John Horton Conway entworfenes, tatsächliches Spiel verwendet wurde. Conways „Game of Life“ basiert auf der ständigen Veränderung von Mustern. Die Veränderungen folgen simplen Regeln: „Lebende Punkte“ sterben, wenn sie weniger als zwei und mehr als drei lebende Nachbarn haben. „Tote Punkte“ werden wieder lebendig, wenn sie genau drei lebende Nachbarn haben. Ob Punkte weiterleben oder zurückkehren ins Leben, hängt von der Dynamik der Umgebung, in erster Linie von ihren jeweiligen Nachbarn ab. Wenn Greiner diesen Titel übernimmt, scheint er andeuten zu wollen, dass auch der Ausstellungsraum als Spielbrett aufgefasst werden kann. Statt Punkte bevölkern ihn Menschen, Hybridwesen, künstliche Intelligenzen oder Objekte. Trotz anderer Parameter ähnelt das Treiben in der Ausstellung Conways Spiel, bei dem sich die Punkte zu immer neuen Mustern ordnen, die wieder zerfallen, sodass ein Rhythmus von beständiger Annäherung und Abstoßung generiert wird. Der Bonsai fährt durch den Raum, macht Fotos, nähert und entfernt sich, die Besucher*innen bewegen sich, erscheinen real und als Bild und werden zum Konversationsgegenstand der Chatbots oder auch nicht. Muster nach Muster, Situation nach Situation entsteht und löst sich auf. Die Tak-tak – tak-tak – tak-tak-Laute, die beständig zu hören sind, wenn die so genannten Flip Dots auf der Tafel in „The Game“ rotieren, begleiten alle Veränderungen im Raum rhythmisch. Es ist ein beruhigender Soundtrack, manchen bekannt von früher, als Bahnhöfe und Flughäfen den Rhythmus der ein- und abfahrenden Fahrzeuge auf rotierenden Anzeigetafeln noch mechanisch abbildeten.

Der Bonsai-Roboter und die Chatbot-Stimmen, die basierend auf dem Wortschatz, mit dem sie trainiert wurden, mit den Rhetoriken und Jargons eines*r Kunsthistoriker*in, eines*r Politikwissenschaftler*in und eines*r Zen-Buddhist*in auftreten, diese technisch-lebendigen Hybridwesen, sind diejenigen, die in Game of Life koalieren, sprechen, dokumentieren. Sie schüren den Eindruck, als eröffne KI neue Räume, neue Möglichkeiten, über die Welt nachzudenken, sie zu sehen.

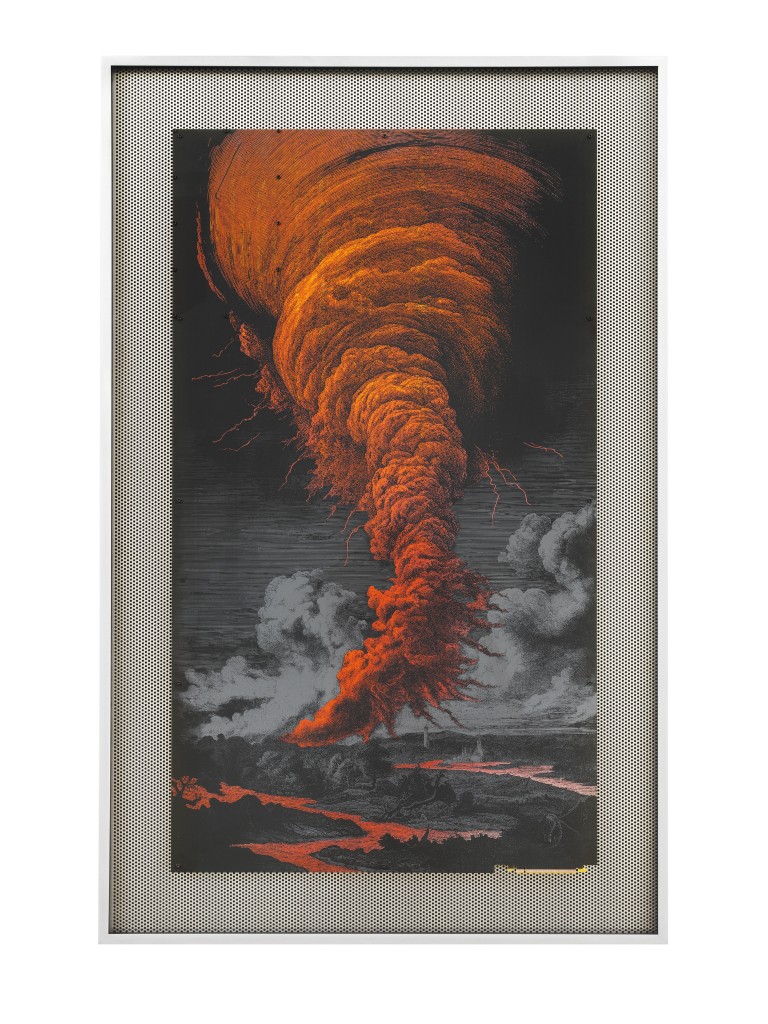

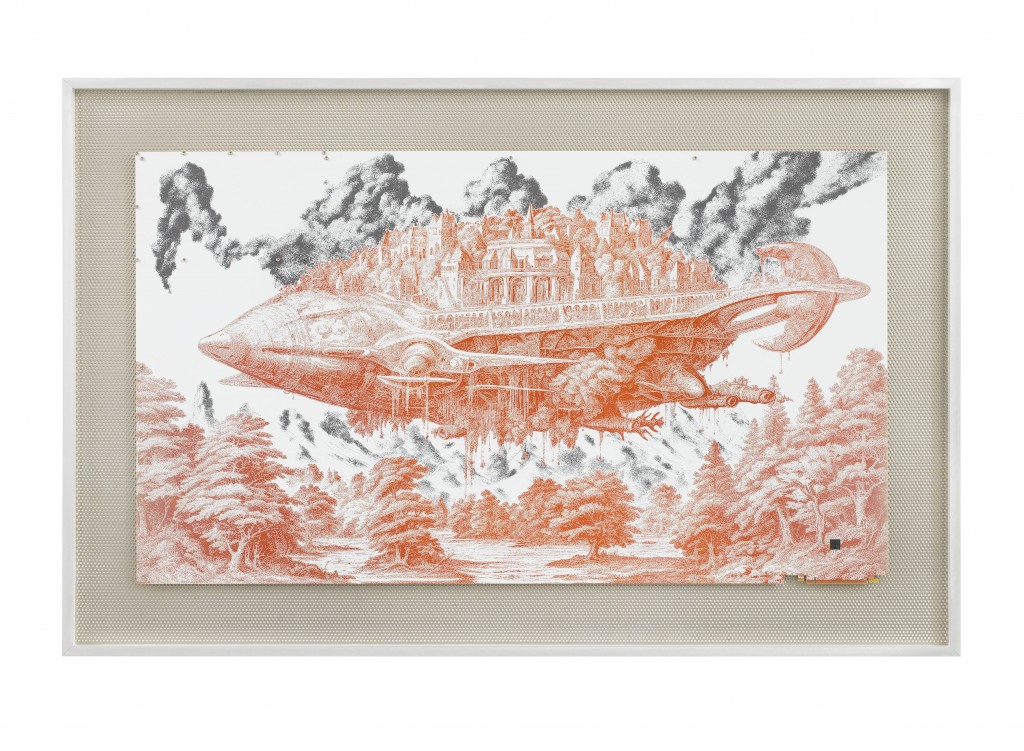

Die spekulative Kraft, die dieser Technik innewohnt, bezeugen auch die Bildwerke im oberen Teil der Ausstellung. Es handelt sich um Bilder auf Mikroplatinen, deren Motive in einem technisch aufwändigen und von Greiner eigens entwickelten Verfahren auf die Platte aufgebracht wurden. Sie tragen Titel wie „Exodus“, „Movement to Venus“, „Blowin’ in the Wind” oder “Five feet high rising” und zeigen dramatische Landschaften sowie phantastische Flugobjekte: Auf einer Darstellung nähert sich ein gewaltiger Tornado, der den Bildraum in Gänze einnimmt, mit voller Wucht einer ruhigen, bilderbuchähnlichen Landschaft, in der ein mäandernder Fluss durch ein idyllisches Tal fließt. Ein anderes Bild zeigt ein nächtliches Seestück mit dramatischem Wellengang. Auf anderen Platinen lassen sich abenteuerlich anmutende Luftschiffe erkennen, die über Wälder hinweg schweben oder gar mit Bäumen verbunden erscheinen, surreale Exemplare des bekannten Zeppelins: Eines der beiden Flugobjekte ist mit einer Burg bepackt und endet in einer auskragenden Rundung. Das andere weist eine fischähnliche Form auf und ist mit einer filigranen, vielfach durchfensterten Fassade dekoriert. Tornados über einer mitteleuropäischen Landschaft und zeppelinartige Luftschiffe, die der Gotik abgerungene Bauelemente aufweisen? Die fragwürdige Kombination scheinbar unvereinbarer Bildelemente erinnert an surreale Traumlandschaften. Doch die altmeisterliche Bildsprache verwirrt diese Überlegung. Wer um alles in der Welt würde sich solche Bilder ausdenken? In der Tat handelt es sich nicht um Werke eines*r menschliche*n Autors*in, sondern um Bildprodukte der Software Midjourney. Aus Schlagworten wie „Baum“, „Architektur“ und „schweben“ erwachsen Bilder. Bilder, die aber keiner menschlichen Vorstellungswelt entspringen und die dadurch nicht nur anders, sondern fremd anmuten.

Wie also stehen wir zur künstlichen Intelligenz, wenn sie in ein altmeisterliches Gewand schlüpft, um uns in nie zuvor gesehene Bildwelten hineinzulocken? Wenn sie als eine sinnierende Instanz auftritt, die über die Welt und ihre Entwicklung spricht? Wenn sie sich mit Pflanzen verbündet, während wir außen vor bleiben? Wie fühlen wir uns, wenn uns das Gefühl der Kontrolle entzogen wird oder wir uns damit arrangieren, es in andere Hände zu legen? Wie bewegen wir uns durch eine solche Welt? Welche Rolle nehmen wir an? Game of Life spielt mit unserem Verhältnis zur Technik. Die Ausstellung schafft einen Raum, in dem sich Beziehungen neu ordnen, in dem neue Formationen entstehen und wandelnde Konstellationen, Annäherung und Abstoßung, in Erscheinung treten. Es erscheint ratsam, diesen Raum behutsam zu beschreiten und Greiners Gedankenexperiment zu nutzen, um neue Fragen daraus abzuleiten, wie wir uns zur Welt um uns herum und anderen Formen der Intelligenz positionieren.

Dr. Christina Landbrecht (*1981) ist Kunsthistorikerin, Kuratorin und Dozentin. Sie lebt in Berlin. Seit 2018 verantwortet sie den Programmbereich Kunst der Schering Stiftung. Dort hat sie in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen von Künstlerinnen wie Sissel Tolaas, Anna Virnich, Jenna Sutela, Susanne M. Winterling und Annika Kahrs kuratiert. Sie hatte Lehraufträge an der Universität der Künste und wird ab 2024 am Bard College Berlin unterrichten.