DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM is pleased to present our first show with MONTY RICHTHOFEN (aka Maison Hefner). Titled CHEAP HEDONISM, the exhibition includes an immersive light and sound experience in collaboration with Yasmina Dexter in the main subterranean gallery space, and will be accompanied by a new series of text paintings and works on paper. The exhibition opens on Friday, January 20, 2023, from 6–8 PM and is on view through March 4, 2023. The gallery and the artist will host a finissage event on Friday, March 3, 2023, with a unique activation of the installation.

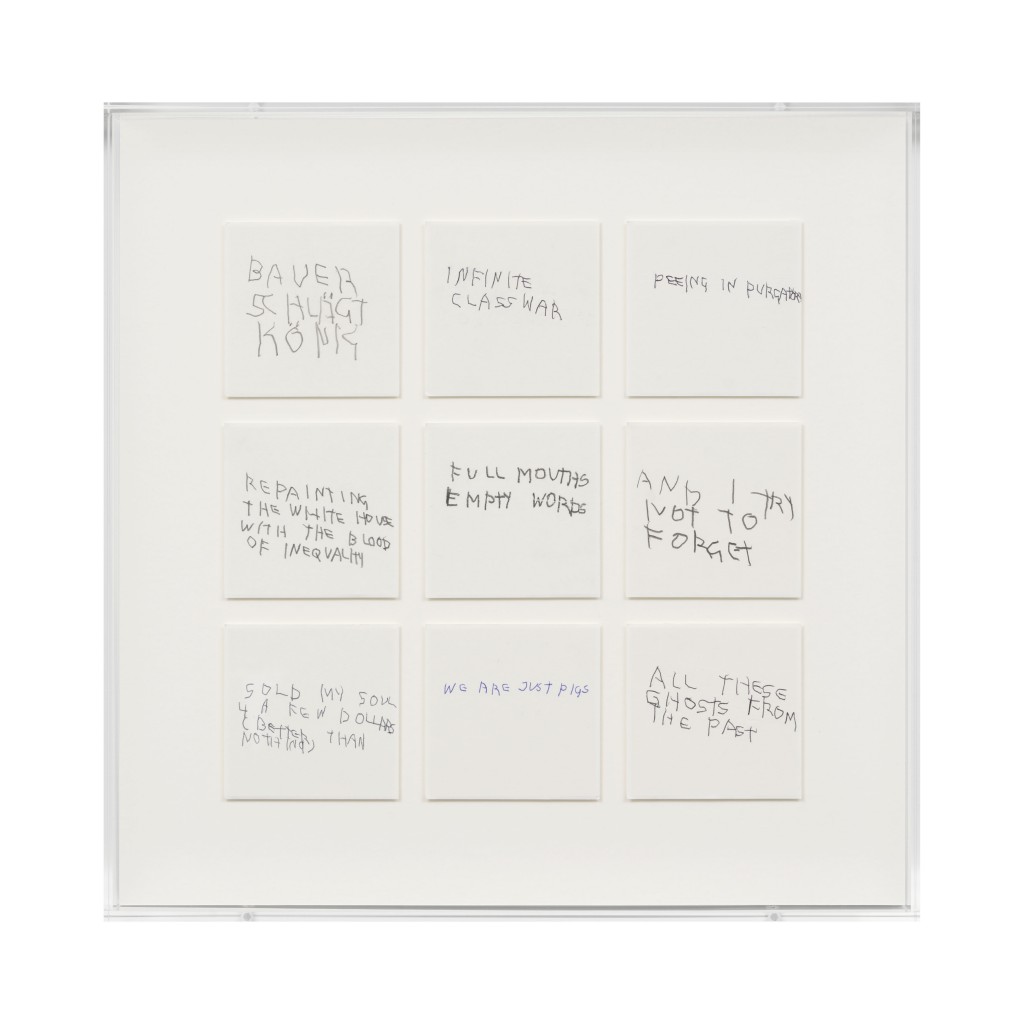

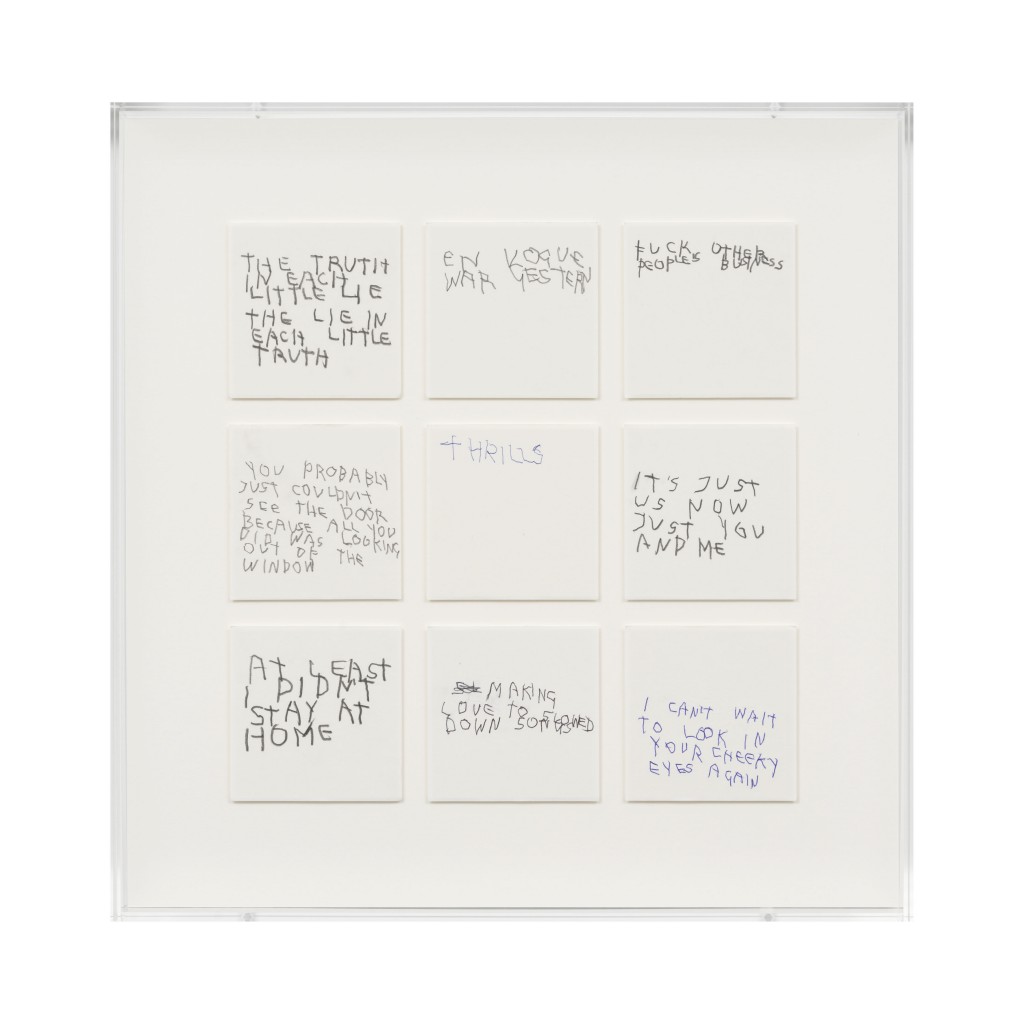

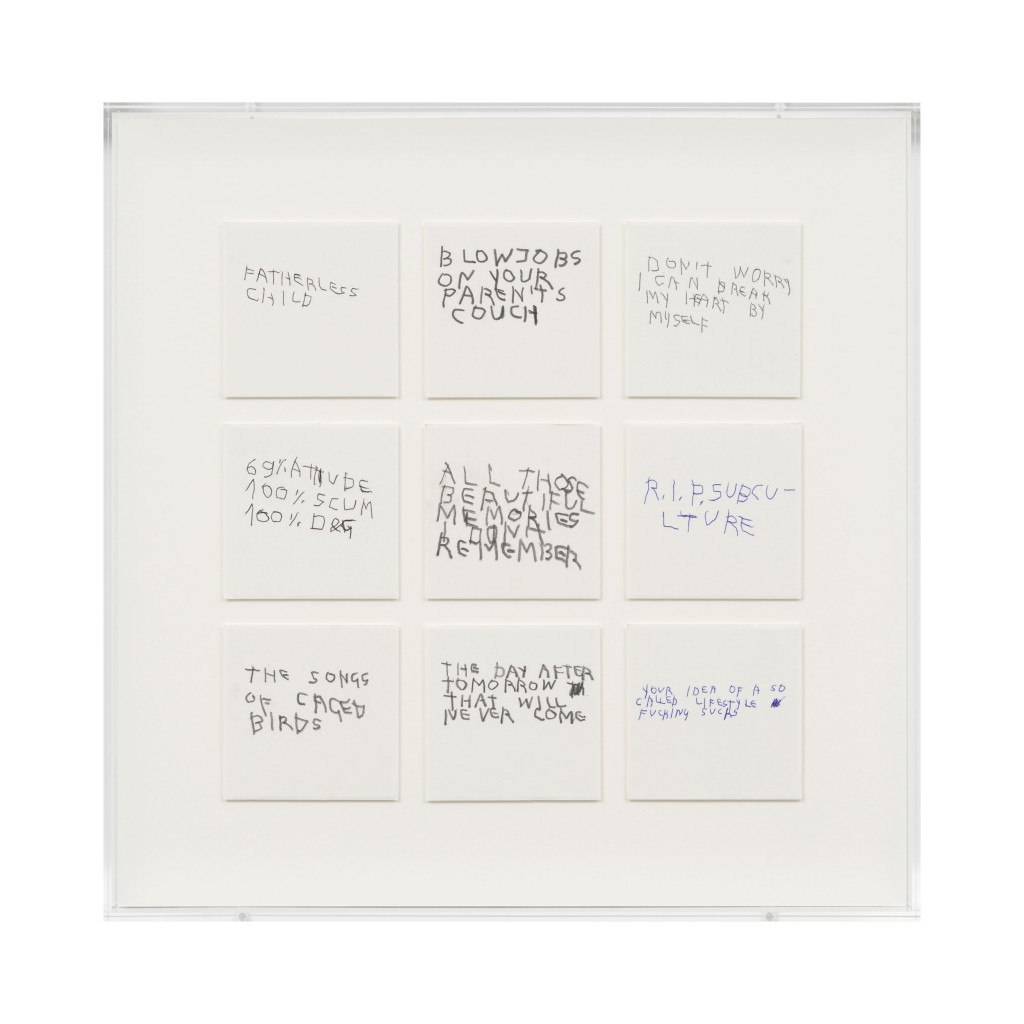

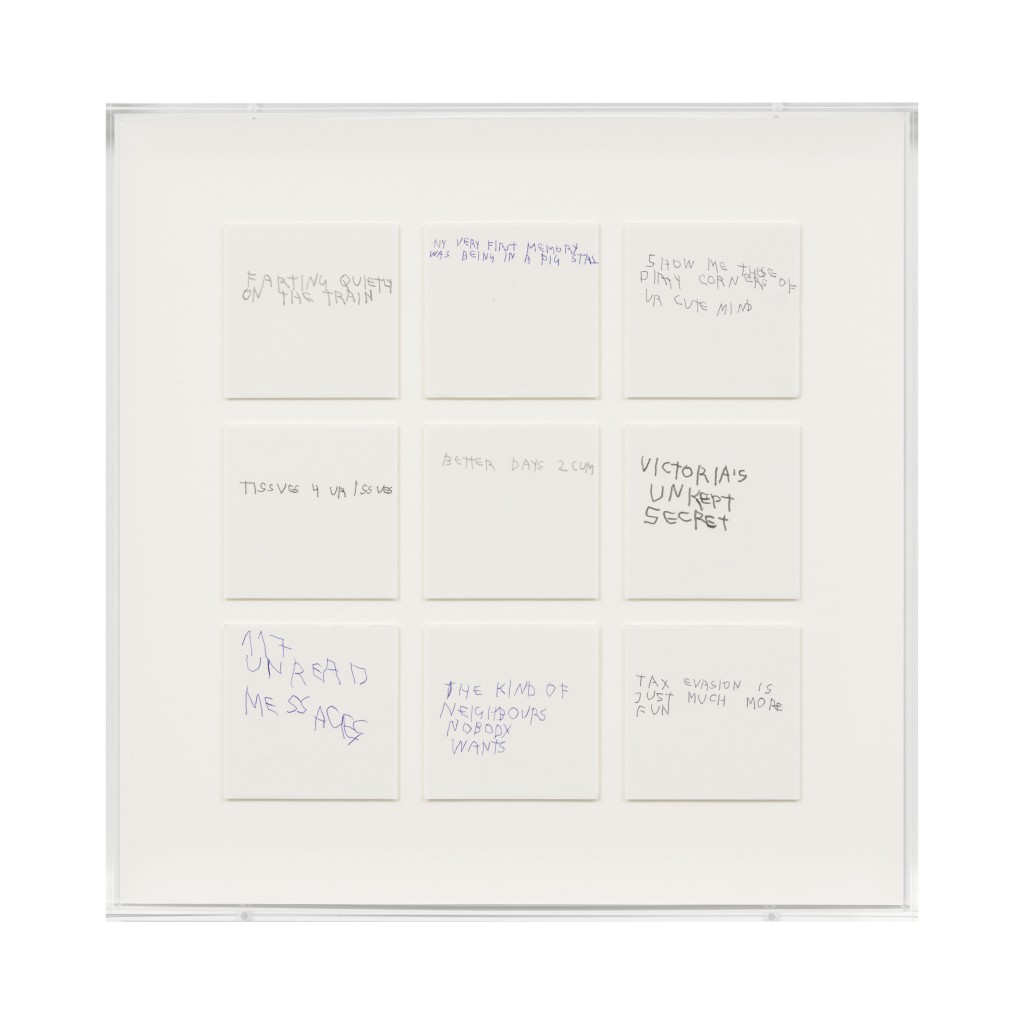

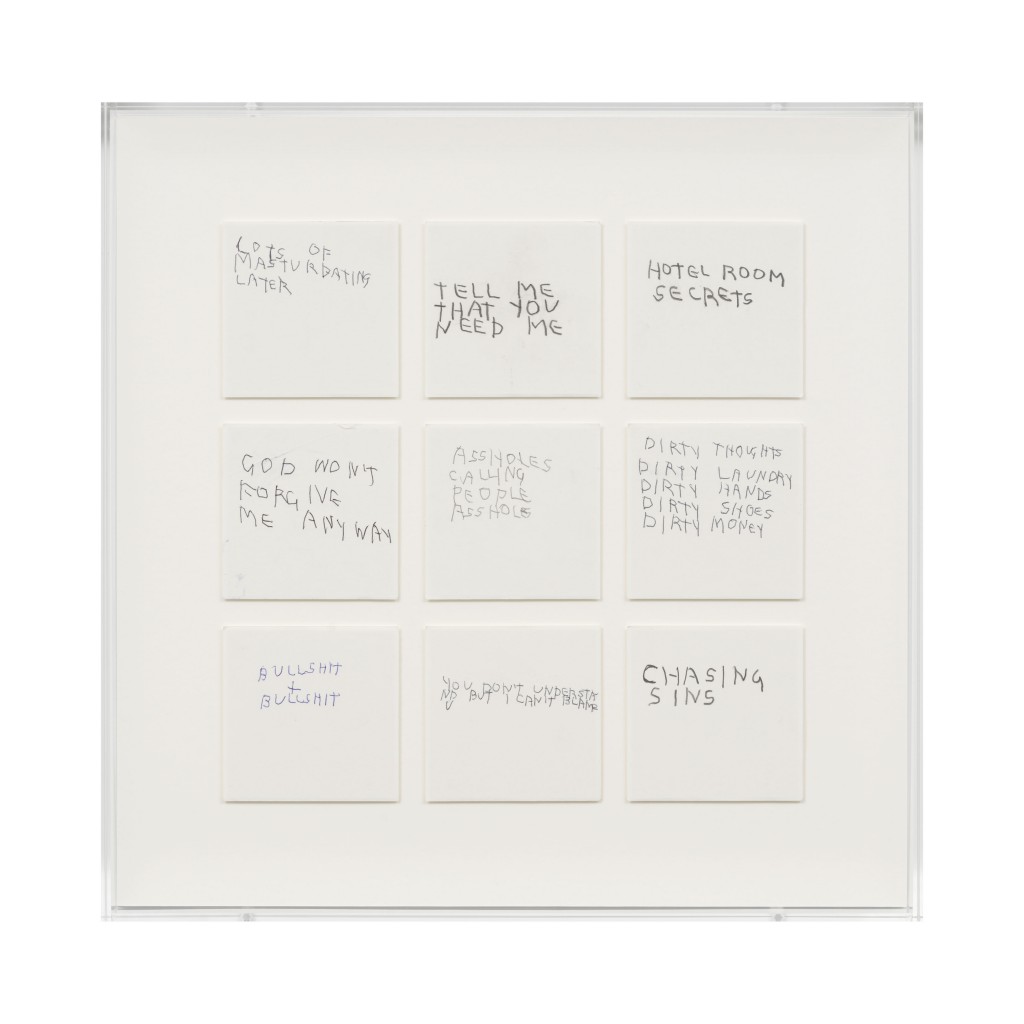

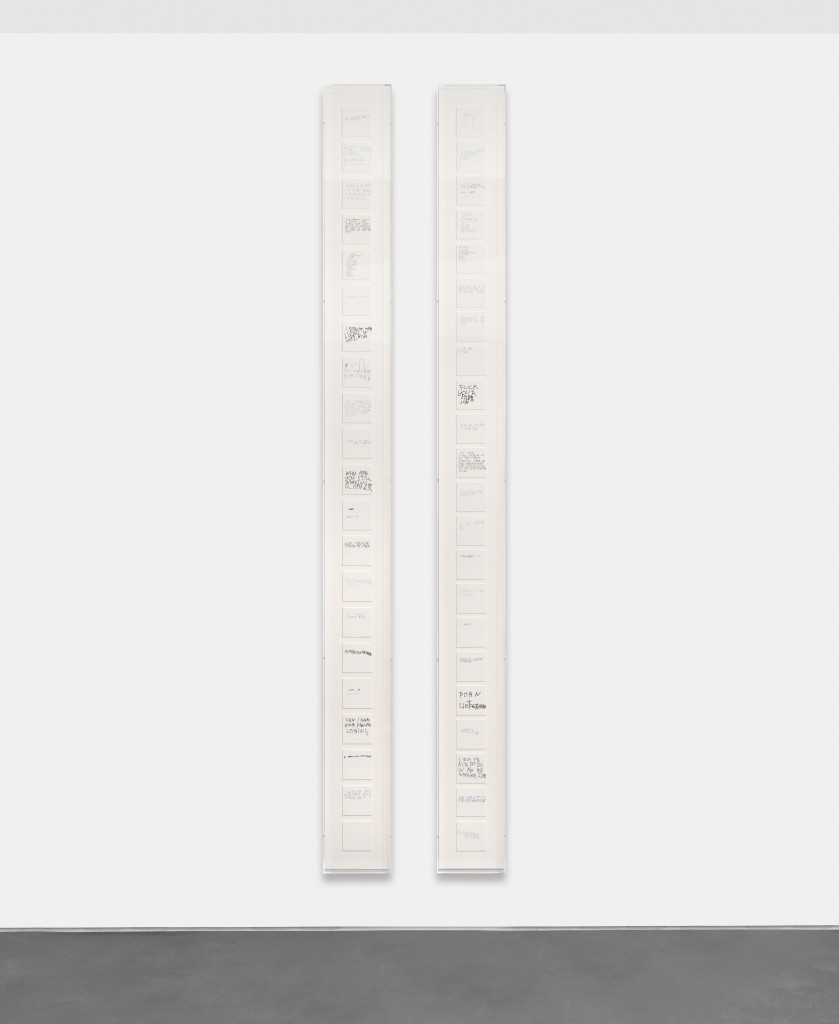

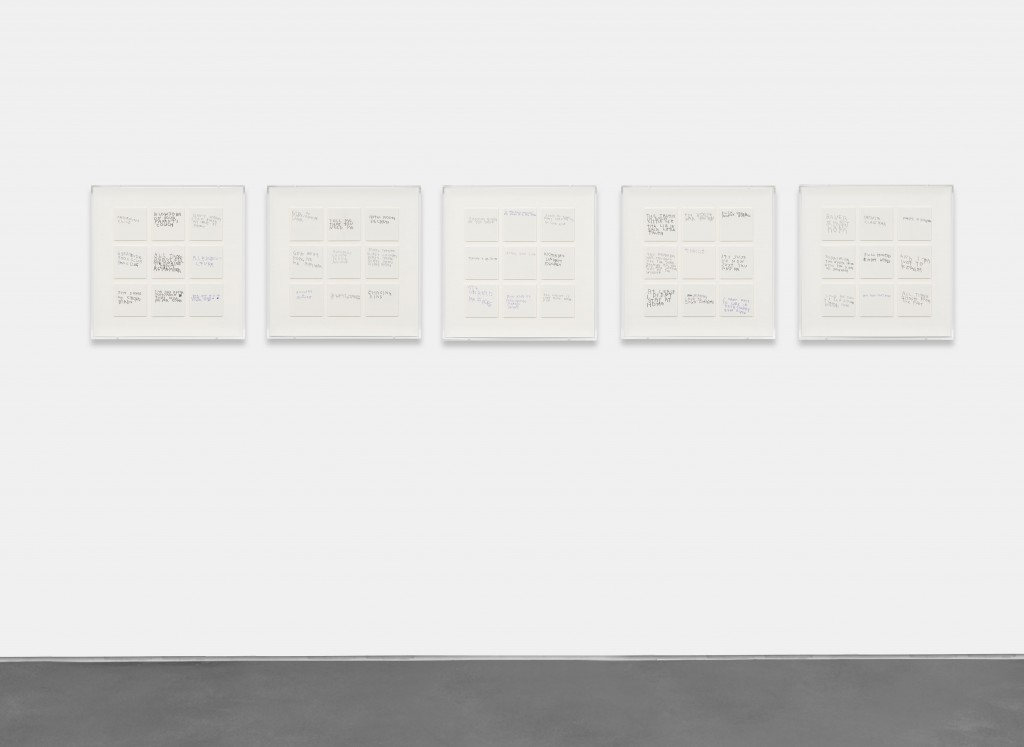

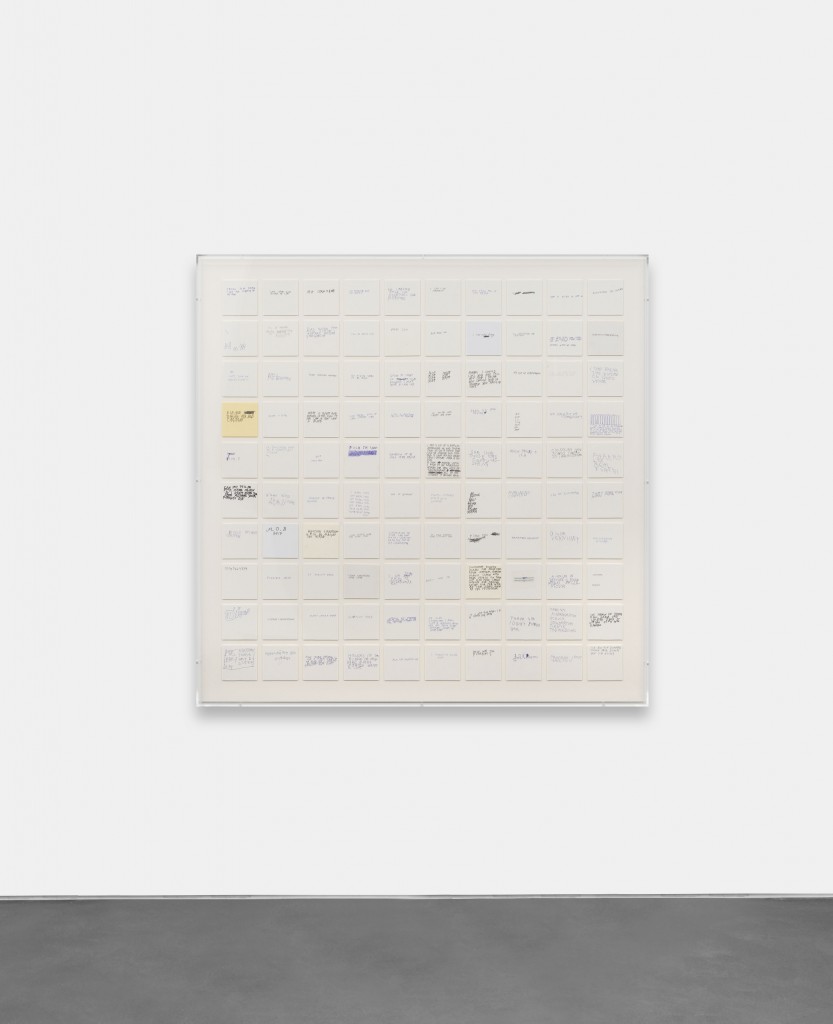

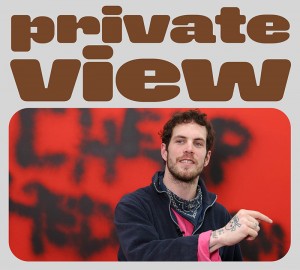

Visitors arriving at the gallery are welcomed by a large-format painting; letters on a luminous red ground spell the exhibition’s title: CHEAP HEDONISM. The sounds of a twenty-minute multimedia installation can be heard from downstairs and guide the visitors toward the gallery’s underground exhibition space. In the anteroom leading to the main gallery, papers reminiscent of square notepads, mounted under acrylic glass covers, reveal intimate notes, phrases, and poetic fragments in Richthofen’s hand. Confronted with the artist’s unfiltered thoughts, the visitors are invited to delve into a reflection on their own feelings and thoughts.

The exhibition’s centerpiece is set up in the main gallery. The installation titled If This Is You Who Am I consists of seven lightboxes spray-painted with acrylic paint that pulse in the rhythm of a two-channel sound file by Yasmina Dexter. Richthofen recorded the texts reproduced on the light boxes; Dexter then subjected the recordings to acoustic manipulation. In the course of the piece, the artist’s spoken words eventually become more and more clearly audible.

Life is not bad at all—perhaps even better?—somewhere in the capitalist system’s interstices. In an age of unbridled consumerism, advancing globalization, and constant availability, we need to subject conventional values to ongoing critical scrutiny. Monty Richthofen’s solo show CHEAP HEDONISM exposes the pitfalls of social life, builds bridges, allows for vulnerabilities. Exuding a sense of ease, it encourages the visitors to linger and immerse themselves in a place where words in their immediacy evoke a poetics of the everyday dreamt up with eyes open or closed. Richthofen dedicates himself to pop-cultural phenomena and life’s profound questions alike, his playful engagement with language undeterred by seemingly unrecognizable paradoxes, sending shafts of bright light down into reality’s putatively dark fractures.

On the occasion of the exhibition, the gallery will publish a catalog of the works with an essay in both German and English, available this February 2023. For further information on the artist and the works or to request images, please contact Billy Jacob, billy(at)dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

Monty Richthofen (b. Munich, 1995), also known as Maison Hefner, studied Performance Practice and Design at Central Saint Martins University of the Arts in London. Since graduating in 2018, he has intensively challenged conventional poetry by visualizing text through painting and writings in public spaces as well as tattooing. He currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM freuen sich, die erste Ausstellung von MONTY RICHTHOFEN (aka Maison Hefner) in der Galerie vorzustellen. Die Schau mit dem Titel CHEAP HEDONISM besteht aus einer in Zusammenarbeit mit Yasmina Dexter entstandenen raumfüllenden Komposition aus Licht und Klängen im unterirdischen Hauptraum der Galerie sowie einer neuen Reihe von Textbildern und Arbeiten auf Papier. Eröffnung ist am Freitag, 20. Januar 2023 von 18 bis 20 Uhr; danach ist die Ausstellung bis zum 4. März 2023 zu sehen. Am Freitag, 3. März 2023 werden Galerie und Künstler die Installation im Rahmen einer ganz besonderen Finissage aktivieren.

Im Eingangsbereich der Galerie befindet sich eine großformatige Malerei, auf deren leuchtendem rotem Grund der titelgebende Schriftzug der Ausstellung CHEAP HEDONISM zu lesen ist. Vom Keller dringen Klänge einer 20-minütigen multimedialen Installation nach oben und weisen den Besucher*innen den Weg in das Untergeschoss der Galerie. Im Vorraum des großen Ausstellungsraums hängen in Plexiglashauben gerahmte und an quadratische Notizblöcke erinnernde Zettel, die handschriftlich verfasste intime Notizen, Phrasen und poetische Fragmente Richthofens offenbaren. In der Konfrontation mit den ungefilterten Gedanken des Künstlers werden die Besucher*innen dazu eingeladen, in die Reflexion ihrer eigenen Gefühle und Gedanken einzutauchen.

Im Hauptraum befindet sich das Herzstück der Ausstellung. Die Installation mit dem Titel If This Is You Who Am I besteht aus sieben mit Acrylfarbe besprühten Leuchtkästen, die im Rhythmus eines Zwei-Kanal-Soundfiles von Yasmina Dexter pulsieren. Die auf den Leuchtkästen abgebildeten Texte wurden von Richthofen eingesprochen und anschließend von Dexter akustisch verfremdet. Im Laufe des Stücks werden die gesprochenen Worte des Künstlers schließlich immer deutlicher wahrnehmbar.

Irgendwo in den Zwischenräumen des kapitalistischen Systems lebt es sich ganz gut – vielleicht sogar besser? In Zeiten ungebremsten Konsums, fortschreitender Globalisierung und konstanter Verfügbarkeit gilt es, konventionelle Werte immer wieder aufs Neue kritisch zu reflektieren. Monty Richthofens Soloausstellung CHEAP HEDONISM offenbart gesellschaftliche Fallstricke, schlägt Brücken, lässt Verletzlichkeiten zu. Es entsteht ein Ort, der in entspannter Atmosphäre zum Verweilen einlädt, an dem Worte in ihrer Unmittelbarkeit mit offenen wie geschlossenen Augen erträumte Alltagspoesien evozieren. Dabei stößt sich Richthofens spielerischer Umgang mit Sprache nicht an scheinbar unvereinbaren Paradoxien, wenn er sich popkulturellen wie tiefgründigen Themen widmet und helle Lichtstrahlen sich in den vermeintlich dunklen Bruchstellen der Realität verlieren.

Zur Ausstellung erscheint ein von der Galerie herausgegebener Katalog der Arbeiten mit einem Essay in deutscher und englischer Sprache, der im Februar 2023 vorliegen wird. Für weitere Informationen zum Künstler und den Arbeiten oder um Bildmaterial anzufordern, wenden Sie sich bitte an Billy Jacob, billy(at)dittrich-schlechtriem.com.

Monty Richthofen (geb. 1995 in München), auch als Maison Hefner bekannt, studierte Performance Practice und Design an der Central Saint Martins University of the Arts in London. Seit seinem Abschluss 2018 stellt er die Konventionen der Dichtung mit Visualisierungen von Text in Form von Bildern und Schrift im öffentlichen Raum sowie Tätowierungen grundlegend in Frage. Er lebt und arbeitet derzeit in Berlin.